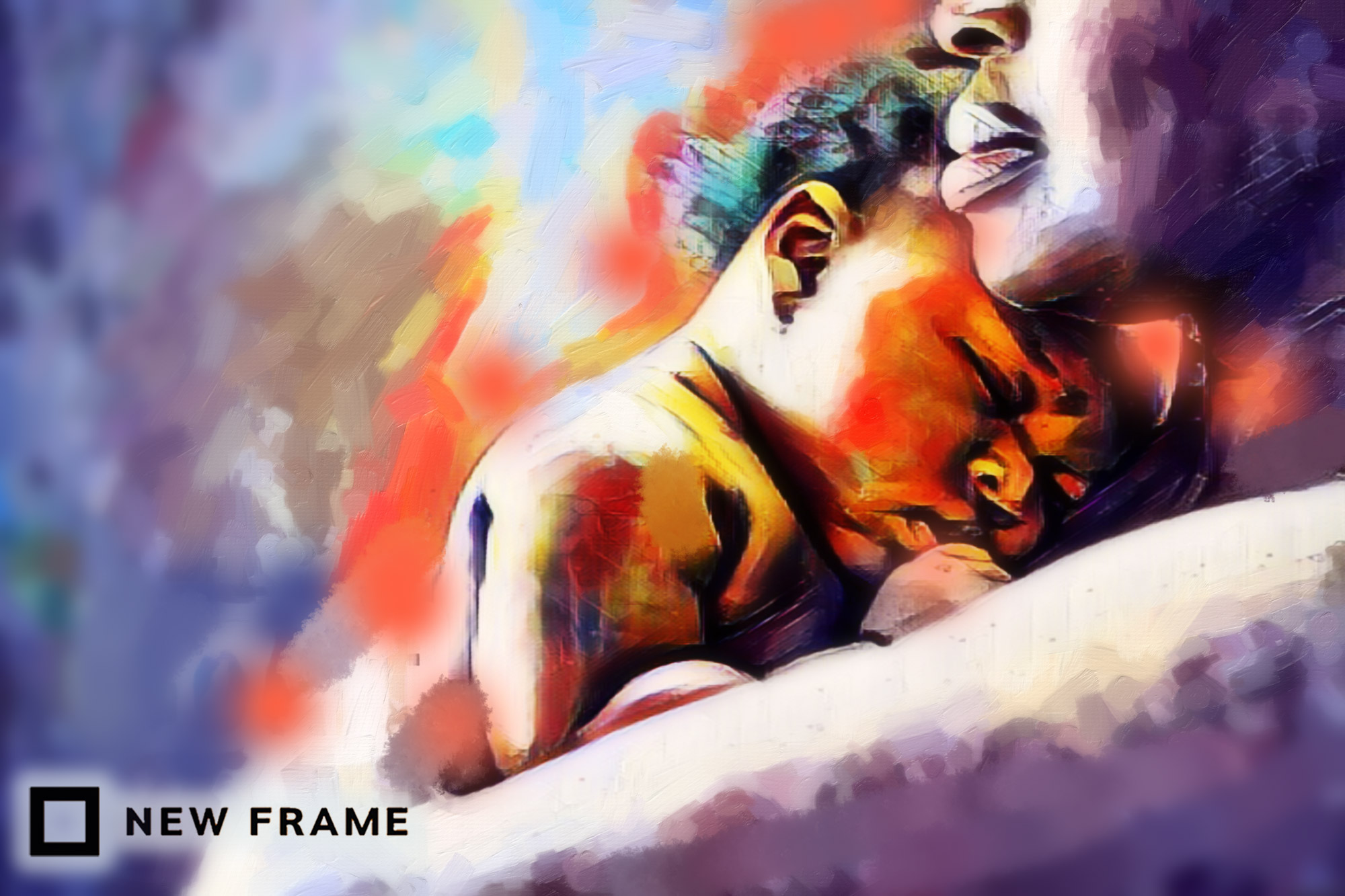

Pain management for children is falling short in SA

The majority of healthcare workers in a survey said children’s pain was not being adequately treated. Too few pain clinics, an overburdened system and a lack of medication all contribute.

Author:

1 June 2022

When healthcare experts from the public and private sectors were asked in a survey how effective they thought infant and children’s pain are assessed where they work, 84% answered it was ineffective.

Behind this shocking number, however, lies a whole series of complexities.

Measuring pain is tricky, even in adults. Pain scales and measurement frameworks depend on people answering questions, or rating their pain on a scale of say one to 10. But many children are not able to self-report their pain. Accordingly, other methods have to be used to assess pain. These include observation of the child’s behaviour and measurement of physiological indicators that may indicate pain, such as pulse rate, blood pressure, temperature and respiratory rate.

Related article:

“The big problem in many healthcare settings is that healthcare professionals have not been taught to assess children’s pain or that they have ‘been taught’ to ignore it and consider it as part of the process. If you don’t recognise it or assess it, you won’t manage it,” says Michelle Meiring, chairperson of the South African Children’s Palliative Care Network (PatchSA) and advisor for the Special Interest Group for PaedsPain (PaedsPainSIG). (Meiring was also behind the survey mentioned at the beginning of this article.)

Meiring says there is inadequate training in pain assessment among practitioners. The management of children at all levels of education among practitioners is also lacking, she says, pointing to knowledge gaps about chronic pain. “Some children with chronic pain are not believed (that they experience pain),” she says.

“Professionals have underappreciated the damage that is done by not treating children’s pain. Not only does it prolong hospital admissions and delay recovery and wound healing, but untreated acute pain can lead to chronic pain. Several studies have shown how undertreated pain in the neonatal period can reset that child’s pain threshold for the rest of their lives,” says Meiring.

Care mismatch

According to the PaedsPainSIG council, 30% of the South African population are children and adolescents, but only 7% of the Pain Clinics in the country are dedicated to children. The council provided comments to Spotlight as a group.

In the public sector, they say the Western Cape is the only province with a paediatric pain clinic, while KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo each have one adult pain clinic, which occasionally treats children. Gauteng, Eastern Cape and the Free State only have adult pain clinics. “Pain services in the private sector are disjointed and largely non-existent, and are largely run by sole practitioners, and not interdisciplinary teams,” says the council.

Related article:

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) established benchmarks on waiting times for treatment of chronic pain in 2009. IASP considered pain in children a most urgent condition, which should be treated within a week after referral.

“It goes without saying that, with only one paediatric pain clinic serving 17 million children and adolescents in SA, we cannot comply with that benchmark,” says the council.

They added that there is a desperate need to increase the capacity for access to appropriate pain management in all the provinces. South Africa needs to focus on creating multidisciplinary teams that can develop low-cost pain treatment strategies with non-pharmacological therapies, such as physical therapy and psychological support.

The role of medicine

According to Meiring, professionals will often say “the system is overburdened; we don’t have enough time” to assess and manage children’s pain. A commonly cited explanation in procedural pain management is, “we don’t have enough time for the local anaesthetic patch to work (it takes 30 to 45 minutes), so we’d rather just hold the child down and ‘get it over with’”, she says.

Internationally there has been increasing recognition that we can do a lot better in relieving children’s pain – maybe most notably from the Lancet Commission on Palliative care and Pain Relief published in 2018. The commission found that: “The core component of the essential package is inexpensive, off-patent, injectable and oral immediate-release morphine. Just more than $1 million would address the unmet medical need for opioid analgesics for children experiencing serious health-related suffering in low-income countries, and $145 million would close the global gap in the need for morphine in palliative care and provide relief to millions of people with preventable pain worldwide.”

The PaedsPainSIG council says this core component of the essential package (off-patent, injectable and oral immediate-release morphine) is freely available in South Africa. “We are very fortunate in comparison with other African countries where the legislation and systems to allow medicinal use of opioids is not in place,” they say. “However, there are still ongoing problems in certain provinces. Last year there were issues in Limpopo and Mpumalanga, but fortunately, this was picked up by national monitoring processes and has been addressed.”

Related article:

Meiring explains it is also due to supply and demand. If clinicians aren’t prescribing enough then pharmacists aren’t preparing enough. Morphine ordering is done based on consumption because the drug needs to be monitored to prevent it from getting into the wrong hands.

“There is still a lot of fear among doctors in prescribing morphine and so there is under prescription. And then there is the fear from the side of the parents. Morphine is, unfortunately, a highly stigmatised medicine and thought of as the death or dying drug, not just a strong painkiller,” she says.

“Even when it is prescribed it may be under-administered. Under-administration happens not only with parents but also with nurses. Because it’s a scheduled drug it has to be locked up in a special drug cupboard and can only be administered by professional nurses. In some hospitals where nurses are short-staffed there may not be enough professional nurses to give out morphine every four hours,” she says.

Breakthrough pain

The management of breakthrough pain is also very difficult in the public sector. Breakthrough pain is pain that breaks through the control provided by regular four-hourly morphine. This sometimes requires a top-up dose before the next dose is due. Doctors will prescribe this on an ‘as needed basis’.

“We find in busy settings this often doesn’t happen because it means that someone has to properly assess the pain in between doses or listen to the parent’s report,” says Meiring.

Related podcast:

Problems are also experienced in some settings with the preparation of oral morphine syrup for children where pharmacists lack proper training or sometimes have equipment issues. An expensive scale is required to weigh morphine powder which also needs to be calibrated frequently.

Apart from a narrow exception for obstetric cases, only doctors can prescribe schedule five and six pain medication in South Africa. Morphine is schedule six. Some have argued that nurses should be allowed to prescribe a wider variety of pain medicines, including morphine. The issue is particularly acute in rural areas where there are few doctors.

Not just morphine

Not all severe pain responds to morphine. Doctors often need to use medications designed for neuropathic pain and these medicines are not always available and are sometimes used off-licence (that is to say not for the purpose for which it is registered). An important example of this is Gabapentin, says Meiring, which is only available in some provinces. This leads to children in other provinces receiving inferior medicine which does not work or does not work as well.

Related article:

“Really difficult pain will sometimes require intravenous infusions of several scheduled drugs that need to be monitored closely for side effects. Ideally, this should be done in high care settings with nurses able to watch closely. Often with bed pressure availability, this is not possible. We sometimes find patients that are seen as palliative care only, are perceived as patients who shouldn’t warrant this level of care which should be reserved for more intensive care unit-type patients who have a chance at survival.”

The paediatric pain and palliative care chapters in the South African Essential Drugs List are currently being revised with the help of Meiring and Anisa Bhettay. National paediatric pain and palliative care guidelines are also being developed under the auspices of the National Department of Health, PatchSA and other professionals.

Lack of specialists

Tragically, most children in South Africa needing pain and palliative care do not have access to specialists in these fields. Many of these functions are performed by non-governmental organisations, academics or public sector employees with special interests in this field who do this over and above their normal duties.

Meiring says to ensure a continuum of care, palliative care especially needs to be provided across settings: from the patient’s home to the tertiary level hospital. There are very few community-based palliative care services for children, which results in many dying or being managed at hospital level.

“Apart from the control of pain and other distressing symptoms, there is a huge need to provide more psycho-social support and spiritual care to families of chronically ill children. These children have extensive needs, which often means someone in the house has to give up work or school to care for them. It cuts deeply into family finances and affects the whole family, including the siblings.

Related article:

“Marriages are often put under strain and there are several single moms battling on their own with little support. Transport needs and repeat hospital visits are costly. There are almost no respite centres in South Africa where children can be cared for to give the families a break,” she says.

An important concept in palliative care is that pain is not just physical, it is total – physical, psychological, social and spiritual. Suffering often evokes existential questions among children and family alike such as: Why is this happening to me? What did I do wrong? And parental guilt.

“I think parents also suffer a lot. Watching your child in pain and not being able to do anything about it must be one of the most terrible things any parent could experience,” says Meiring.

This lightly edited article was first published by Spotlight.