Our veins do not end in our bodies

Covid can only be contained with global solidarity. Shutting borders is as irrational as it is prejudicial.

Author:

6 December 2021

World Aids Day was marked last week. We were reminded that about eight million South Africans have HIV. There can be few of us who do not love at least one person who has the virus. Most people who have the virus know their status, are on treatment and have undetectable viral loads as a result.

There is much that could be done better, and much that is still to be done to manage this pandemic. Nonetheless, the fact that South Africa has the largest antiretroviral programme on the planet, with about five million people on treatment, is a remarkable achievement.

It has often been said that the antiretroviral treatment programme is the ANC’s most significant achievement, a shining exception to its egregious failures in areas such as employment, housing, land reform, violence against women and much more. But we must not forget that this achievement was won in struggle.

Beginning in the late 1990s, the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), with roots in both the movement for queer liberation and the Marxist Workers’ Tendency of the ANC, built a mass movement and allied with trade unions, lawyers and intellectuals. Avoiding the always destructive and sometimes lunatic forms of sectarianism that often consign the Left to shrill irrelevance, the TAC built a moral consensus that drew in a wide range of actors with divergent political views.

Related article:

The movement took on and defeated the denialist project led by Thabo Mbeki, and the quackery of figures outside the ANC like Anthony Brink, Rian Malan and Credo Mutwa. It also took on and defeated the massive corporate power of the pharmaceutical companies. Unlike many social movements, it was able to develop a positive and practical vision for change, which has been implemented to a significant degree.

There are few social movements in recent memory that have won such decisive victories so quickly – victories that have made a huge difference to so many people’s lives. We face many other medical crises, such as tuberculosis and diabetes, that could be meaningfully alleviated if the right constellation of social forces were able to focus sufficient force on the right targets. Those targets exceed the state and the pharmaceutical companies. In the case of diabetes, the companies that manufacture and sell drinks with a high sugar content need to be met with the same kind of public information campaigns and regulation that have begun to limit the damage done by tobacco.

At a planetary level

There is much that a health movement, or effective health activism by existing social forces, could achieve with regard to Covid. As Zackie Achmat, who led the TAC to a series of victories, observed on World Aids Day, bringing the Covid pandemic under control will require “smart, persistent and radical activism; the broadest front to stop profiteering”.

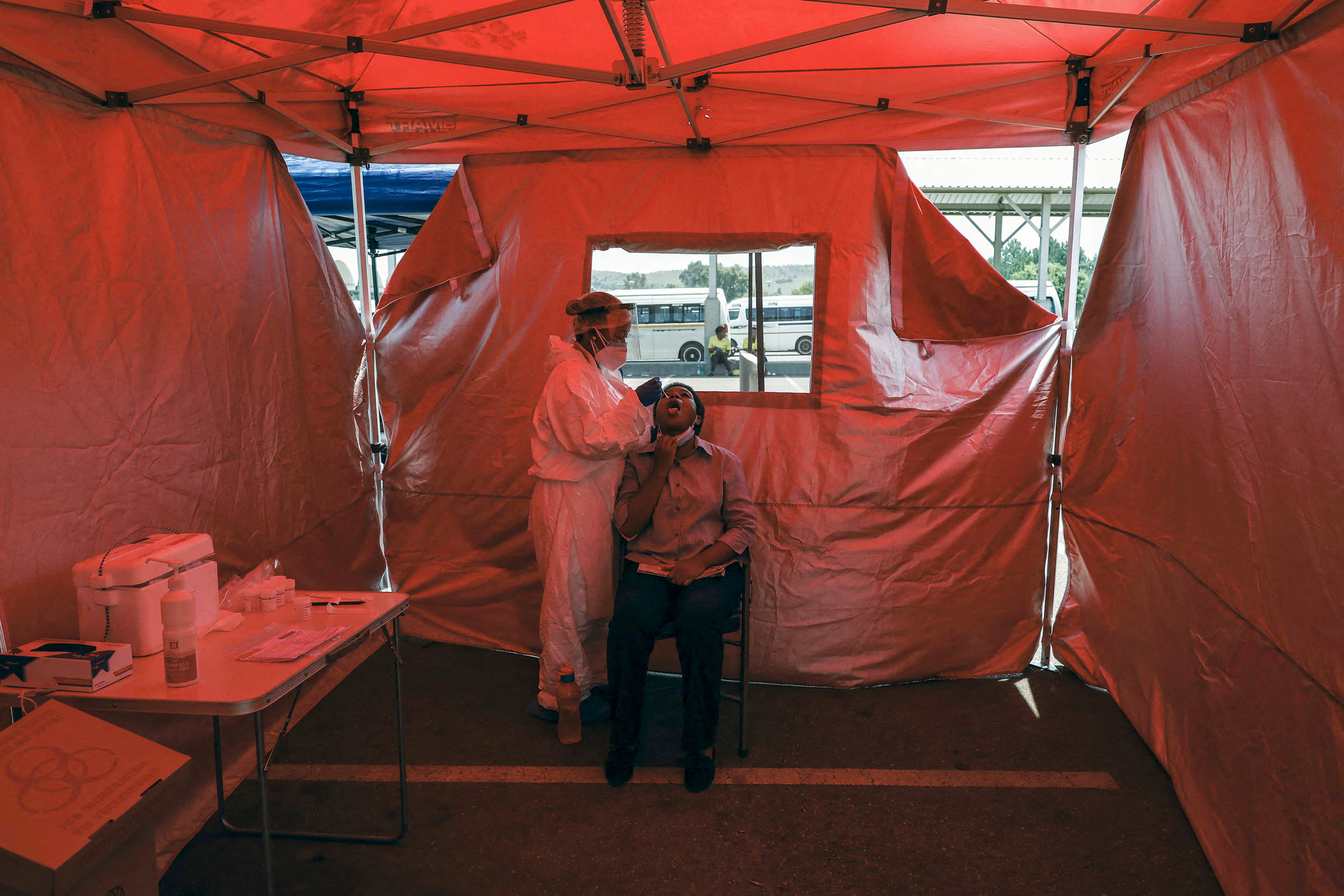

Testing should be widely accessible, free and, if not entirely decommodified, at least radically reduced in cost. There should be a massive campaign to make scientific information accessible to all, carried out in alliance with existing popular forces such as trade unions.

There are real prospects for this kind of popular science campaign. Trade union federation Cosatu made the decision on Monday 29 November to support vaccine mandates, despite vigorous opposition from the National Education, Health and Allied Workers’ Union. The South African Federation of Trade Unions made the decision on Thursday 2 December to do all it could to persuade workers to get vaccinated. And shack dwellers’ movement Abahlali baseMjondolo has long called for a state and societal Covid response rooted in the best available scientific information.

Related article:

But there are also issues that need to be dealt with at a planetary level. The most urgent of these is that neither the production nor the distribution of vaccines can be left to the market. Vaccines must be developed, manufactured and distributed on a social basis. If this is not done, a few corporations will continue to amass vast wealth that should be invested in public health. Vaccines must be allocated on the basis of need, not wealth.

This is a matter of principle. But for those bereft of principle it is also a strategic necessity. An immunised population in a rich country will not remain safe in perpetuity if people elsewhere in the world are not afforded the same protection. Without a genuinely global vaccination programme, as was achieved with smallpox and polio, the Covid crisis will spin across the planet in an endless vortex.

Woven together

It is equally imperative that Covid is not managed in isolation from wider health problems. Although it is too early to make definite conclusions, one of the hypotheses with regard to the origin of the Omicron variant is that it may have developed in the body of a person whose immune system was compromised by an untreated infection.

As a report by the United States public radio channel NPR explains: “The person’s immune system is still strong enough to prevent the coronavirus from killing the person. But it’s not strong enough to completely clear the virus. So the virus lingers inside the person for month after month, continually reproducing. With each replication, there’s a chance it will acquire a mutation that makes it better at evading the person’s antibody-producing immune cells.”

If this hypothesis proves correct, the rich and the impoverished are inextricably bound together despite the fences and armed guards that divide the Earth into countries. It would mean that the imperative for global solidarity, for a planetary commitment to public health rather than closing borders, is even more urgent than originally understood.

Aragorn Eloff wrote a beautiful and profound piece in August on the ways in which human life is woven together, the ways in which “we grow in the same field, from the same soil, as all those around us, and we rely on each other in every way”, the ways in which “freedom and equality nurture each other” in what radical feminist Silvia Federici calls the “endless harvest of the possibilities of the flourishing of human life”.

Related article:

Eloff ended his piece with a poem by Roque Dalton, a Salvadoran socialist. It speaks movingly of the political challenges of our times:

I believe the world is beautiful

and that poetry, like bread, is for everyone.

And that my veins don’t end in me

but in the unanimous blood

of those who struggle for life,

love,

little things,

landscape and bread,

the poetry of everyone.