Organise or starve: Uniting jobless workers

In a book about the Unemployed Workers’ Movement, Shaheed Mahomed recounts witdoeke attacks and how a mass movement of shack dwellers came together to resist forced removals.

Author:

6 April 2022

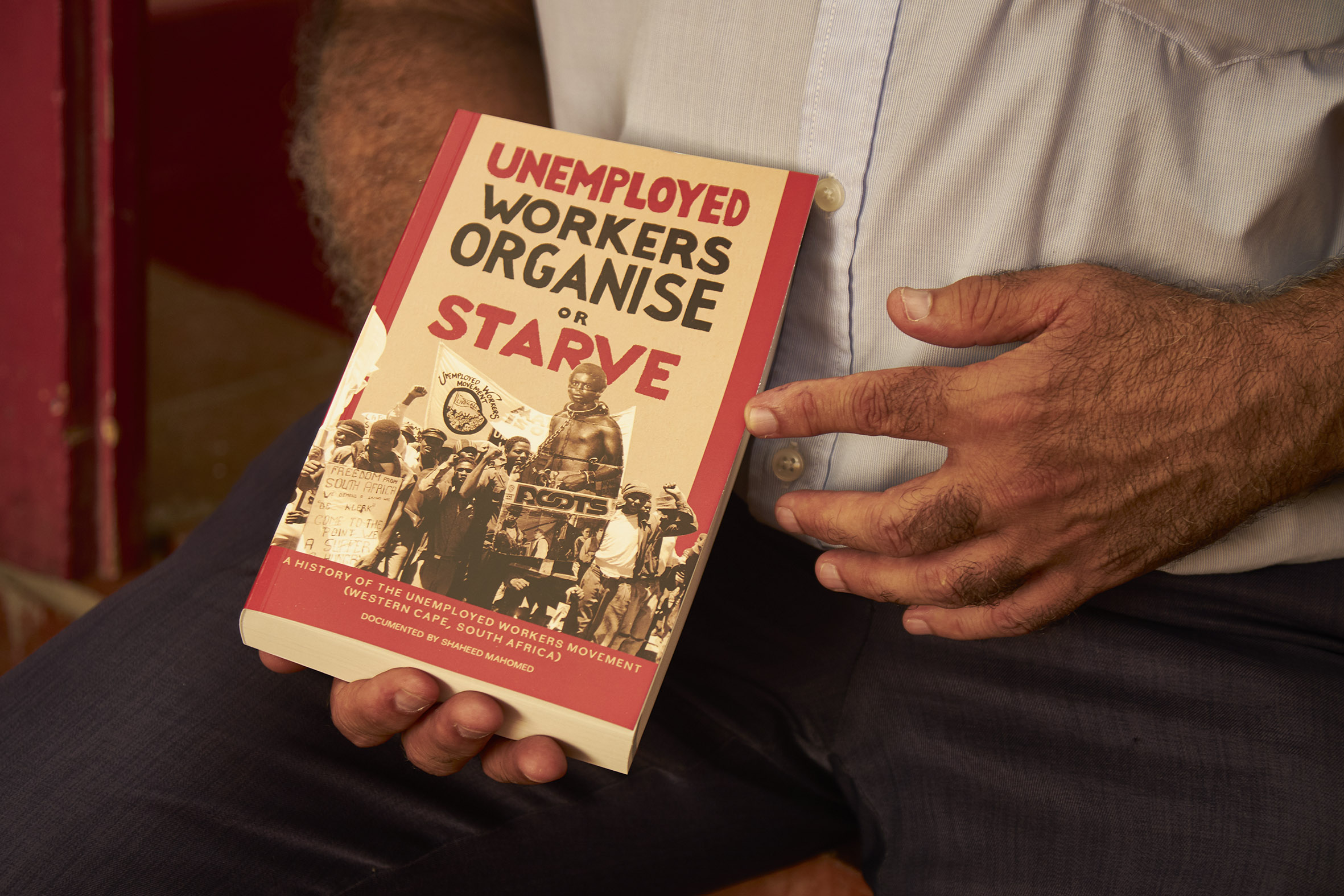

The launch of Shaheed Mahomed’s book on the history of the Unemployed Workers’ Movement (UWM), Unemployed Workers Organise Or Starve: A History of the Unemployed Workers’ Movement (Western Cape, South Africa) (self-published, 2022), featured activists who fell victim to the witdoeke attacks on Crossroads in 1986.

The attacks are similar to what members of shack dwellers’ movement Abahlali baseMjondolo are experiencing now, especially in eKhenana, where they face state repression. Twenty Abahlali members have been assassinated since the movement was launched in 2005, the most recent being Ayanda Ngila, who was shot during the day at eKhenana by people said to have ties with the ANC.

Unemployed Workers Organise Or Starve, which was launched at Cape Town’s iconic Community House on 6 March, describes how witdoeke paramilitaries (local thugs aligned with the apartheid government who wore white cloths on their heads) burnt down the Portland Cement shack settlement, and parts of Nyanga Bush, Nyanga Extension and KTC, displacing more than 60 000 people. While that was happening, the apartheid police carried out a mass forced removal of the Crossroads community.

UWM member Nomasami Mpayipeli recalls in the book that “churches were full of Black people being burnt by Bernard (an apartheid operative). Helicopters were dropping fire and hot water.”

Nowayitile Kente, also a member of UWM, shares her experiences of that attack: “We were running in the bushes, police were pouring hot water and a woman with a baby on her back caught the hot water on her back. I was six months pregnant and my water broke after I saw that. That woman burned so much I don’t think it was possible for her to survive and the worst thing is I didn’t know how to help her.”

Immediately after this, community members set up grassroots patrols against the witdoeke, and UWM members from other communities moved into New Crossroad in support. “Every night, we would be on patrols, it was just to make sure that the witdoeke didn’t come in to attack. You had to contend with the Casspirs as well and the police with the floodlights, and the R1 rifles, and the fuckers could shoot at you anytime,” says UWM member Sharief Cullis in the book.

This was the period when the UWM became a mass movement, building a base of hundreds of members in Crossroads alone. But they continued to face violence from those who collaborated with the apartheid regime.

The UWM based in the Western Cape, which was active from 1984 to 1993, united hostel dwellers and shack dwellers to take over land close to city centres, resist apartheid forced removals, take basic food from supermarkets during mass actions and discourage unemployed people from acting as temporary labour during strikes.

Related article:

The author of the book, Mahomed, is a maths lecturer and high school teacher who was one of the original UWM members. He has worked as a union organiser and was part of the Western Cape Anti-Eviction Campaign, the Anti-War Coalition, the Workers’ International Vanguard League and the Socialist Revolutionary Workers’ Party.

The book is dedicated to UWM activists Mzwandile Matjikiza and James Boesak of Crossroads who were killed on 27 October 1989 by “unknown assassins”. Speaking at the launch, historian at the University of the Witwatersrand Noor Nieftagodien said the book was a socialist history that placed the experience of workers at the centre of their own stories and a timely reminder that the liberation history of South Africa should not be reduced to only the role played by the ANC.

The book itself describes a three-year campaign that the ANC, displeased with the UWM’s socialist orientation, carried out against the movement. Two ANC structures – the Advice Office Forum and the Unemployed Workers Union – were launched to organise unemployed workers, but were unsuccessful and ended up merging with the UWM.

At one point, the ANC tried to ban the UWM from calling any meetings in New Crossroads. “This was the strongest area of the UWM. The suspension was to last from 1987 to 1989, also under the period of the heaviest state repression, the second state of emergency,” the book recounts.

Worker unity

The book is also a testament to strong women leaders. After the forced removals in Crossroads in 1986, UWM chairperson Shirley Mafenuka turned her home into a centre for food and aid distribution. According to the book, “Their home became one of the centres of resistance from which patrols were organised against possible attacks from state-backed vigilantes.”

Other prominent women leaders were Sindiswa Nunu, who was imprisoned for resisting the forced removals and was one of the first to announce that she would rebuild her shack in the area, and Lavender Hill sisters Cynthia and Monica Onkers, imprisoned after their home was raided and the apartheid police found UWM posters and pamphlets.

The book also describes the well-known bread and milk campaign, which launched in Khayelitsha on 25 April 1990 and ran until 1993. “We used to go to Shoprite and Pick n Pay, meet with workers to tell them we were coming and once we had 200 people inside, then we sat down and took bread and milk and consumed it. It happened from Cape Town to Plettenberg Bay, up the West Coast to Atlantis. At that time the companies were throwing unsold milk down the drain and meat into the sea,” writes Mahomed.

Worker unity is one of the most valuable lessons unpacked by the book. The UWM believed that unemployed people are workers without jobs and must unite with unionised workers if they are to make political gains. Focusing only on the immediate need for survival and remaining disconnected from organised workers would have left the UWM without a mass base.

“Most of our activities we did as worker to worker without the union leadership. We didn’t say that because we were unemployed, we were not workers,” Mahomed writes.

The UWM’s deliberate policy of unity in action with employed workers led it to join 33 strikes at supermarkets, metal manufacturing plants, vineyards, South African Breweries and other workplaces. UWM activists also went into hotels where workers were on strike and slipped pamphlets under the doors of guests explaining the strike.

Nieftagodien recommended that activists use the book as a blueprint for organising the unemployed into a non-racial movement. “The only way to produce anti-racism and non-racialism is to do it in practice,” said Nieftagodien. The UWM did this through its members “moving across the railway line” that divided Cape Town’s Black, white and so-called coloured areas and by living and working in areas that the apartheid government tried to prevent them from visiting, Nieftagodien concluded.

The book includes historic photographs of joint marches held between the UWM and unions, and even copies of 1970s eviction notices.

In its time, the UWM achieved many victories. Not only did it prevent forced removals and bolster strikes that succeeded in winning gains for union members, but it also forced many big companies to hire unemployed people and refused to move from pockets of land in Cape Town, Plettenberg Bay and other areas that shack dwellers still occupy today. As the UWM’s former leader in Plettenberg Bay, Zamile Xipula, said at the launch: “When I joined UWM, I was homeless. But we succeeded in fighting for the land.”

Former UWM leader Nunu closed the launch, saying, “It is clear to all of us that the unemployed will not be taken care of by those in power. We have to stand up and do something. This book has paved the way. The memories will help us to collect our minds and see which way we are going to turn.”

Unemployed Workers Organise Or Starve: A History of the Unemployed Workers’ Movement (Western Cape, South Africa) can be purchased at Clarke’s Bookshop, Surplus Radical Book Store and SA History Online.