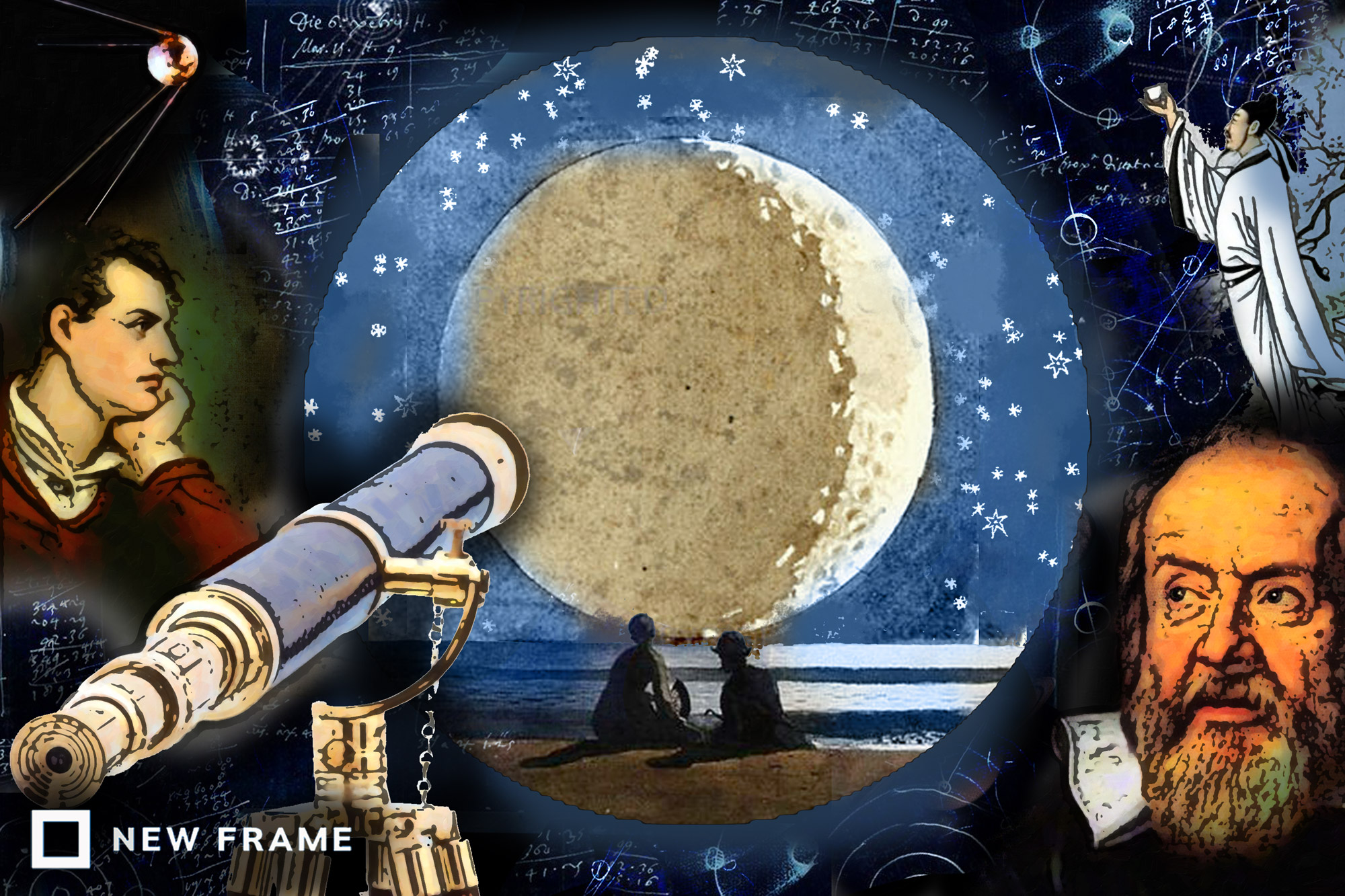

Odes to the moon

In Text Messages this week, humans continue to desecrate the lunar body despite centuries of prose and discovery that capture its elusive and alluring magic.

Author:

17 February 2022

And so, yet another human-made object hurtles towards the moon, set for an unplanned impact on 4 March. First thought to be the upper stage of a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, the hunk of metal gadgetry now is said to be of Chinese manufacture. Whatever its origins, when it crashes into the moon, it will not be the first such assault.

Luna 2, the Soviet moon mission after the Soviet Union had stolen a march on the United States by launching its Sputnik satellite on 4 October 1957, landed in 1959, successfully releasing sodium gas so that the event was visible from Earth. It was the first of what are reckoned to be more than 100 sites on the moon with space junk, lunar despoliation like that of the thousands of oxygen canisters littering Mount Everest.

It is difficult for the poetic, the romantic and the environmentally sensitive to think about the moon being battered in this way. Even worse, next up is lunar mining, with China and Russia likely to be involved in what is practically and ethically a rush to the bottom: the absolute nadir and pits of humankind’s noxious presence in the universe.

Related article:

A group of independent scientists has tried to lend our celestial friend some protection by drawing up The Declaration of the Rights of the Moon, which asserts the moon’s “right to exist, persist and continue in its vital cycles unaltered, unharmed and unpolluted by human beings”. It is a sentiment that would have been understood if not necessarily shared by Galileo Galilei, born on 15 February 1564, 458 years ago this week.

By improving the first prototype spyglass with a magnification of about three, made in Flanders and brought to Venice for sale, Galileo invented the telescope, with a magnification of between eight and 10, the first step on the road to all the mega-far-seeing telescopes we have today. In March 1610, Galileo published Siderius Nuncius (The Starry Messenger), perhaps one of the most Earth-shaking books ever. In it he presented to the world the first published moon maps, done in watercolour. “It is a most beautiful and delightful sight to behold the body of the moon,” he wrote. (Astronomers and aesthetes might like most his wash drawings of the phases of the moon he observed using one of his telescopes in that fateful year of 1610.)

But, as we know, 23 years later Galileo was brought before the Holy Office of the Inquisition at the bidding of Pope Urban VIII and asked to recant and abjure his beliefs and writings. Almost 70, sick, and twice shown “the instruments of torture” – the rack – he relented on 30 April 1633. (He had started professional life as a doctor, so knew better than most what the rack was capable of inflicting.) The significant words, the utter and humiliating repudiation of his defence of Copernicus’ theories, not even his own, are: “… I must altogether abandon the false opinion that the sun is the centre of the world and immovable, and that the earth is not the centre of the world, and moves”.

‘The light of the moon’

On being released by the Inquisition, Galileo is said to have looked skywards, then down at the ground, then stamped his foot and said quietly, “e pur, si muove (and yet, it moves)”. First mentioned in 1757, this anecdote is probably apocryphal, but nonetheless very apposite.

Centuries before Galileo, Tang Dynasty poet Li Po (701-762 CE; also known as Li Bai) savoured the moon as much as the later astronomer. His most celebrated poem depicts how he is drinking with the moon and his own shadow for company. The popular legend around Li Po’s death is that while drunk he leaned out of the boat he was in, trying to capture the moon’s reflection on the water, fell in and drowned.

Few have captured that elusive and alluring magic of the moon as pithily as Lord Byron, in the three stanzas of “So we’ll go no more a roving”.

So, we’ll go no more a roving

So late into the night,

Though the heart be still as loving,

And the moon be still as bright.

For the sword outwears its sheath,

And the soul wears out the breast,

And the heart must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

Though the night was made for loving,

And the day returns too soon,

Yet we’ll go no more a roving

By the light of the moon.

Such must have been how Galileo felt after his abjuration, when he was placed under the strictest house arrest in his villa outside Florence. The starry messenger who had defended Copernicus and the freedom to think and hold ideas went blind and died aged 77 in 1642. In the slowest of retractions and apologies, the Roman Catholic Church’s error in persecuting Galileo was formally acknowledged by Pope John Paul II in October 1992.