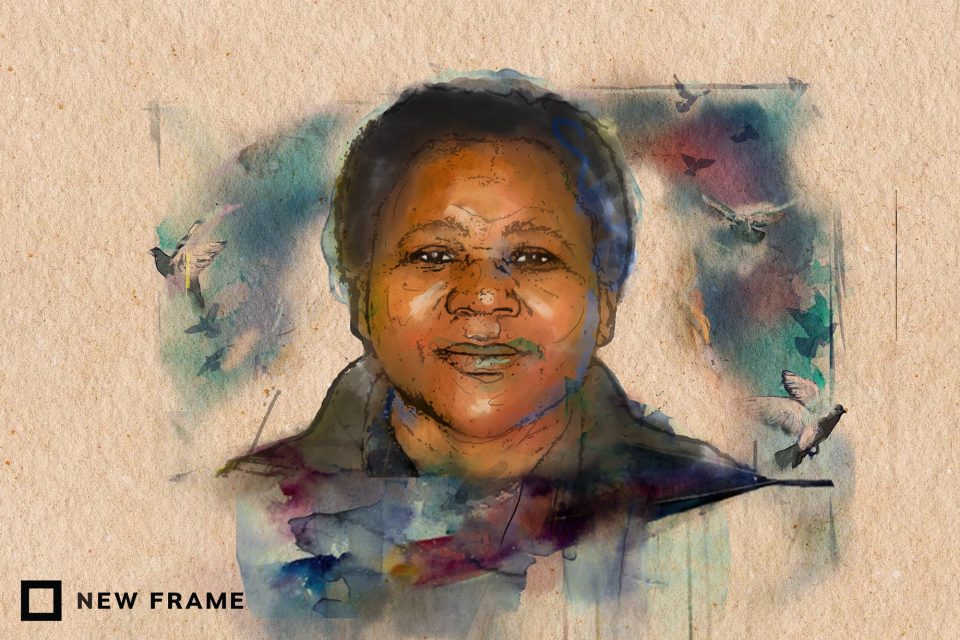

Nyameka Goniwe, a champion of the people

The former mayor from Cradock spent her life advocating for those in her community and fighting for justice for her husband and the rest of the Cradock Four.

Author:

10 September 2020

In June, Nyameka Goniwe was not feeling well and underwent a test for Covid 19. The test was negative but in August, when she again presented with symptoms of the coronavirus, her son Nyaniso encouraged her to have another test. She was waiting for these results when she died at home in Cradock on Saturday 29 August. She was 69 years old.

The results of the second test were negative, but they arrived too late for the woman President Cyril Ramaphosa lauded two days after her death as someone “devoted … to the betterment of the lives of the communities in which she lived. She played various leadership roles in local government in the service of her community and exemplified ethical leadership that put people first.”

He added that “Cradock’s loss is South Africa’s loss. But Nyameka Goniwe will live on in our history and in her enduring legacy of struggle, service and the inspiration and upliftment of communities.”

Related article:

In The New York Times, Alan Cowell remembered Goniwe as “an activist, politician and social worker who survived the death of her husband in one of apartheid-era South Africa’s most brutal extrajudicial killings and went on to campaign in vain for his assassins to be brought to justice”.

Her nephew Mbulelo Goniwe told the Daily Maverick that the family will remember her as a woman who “liked living. She tried to be happy no matter what the circumstances were and was always attempting to make the best of every day. When I think of her, I will always remember how she went out of her way to help others, even if it was to her own detriment.”

The Cradock Four

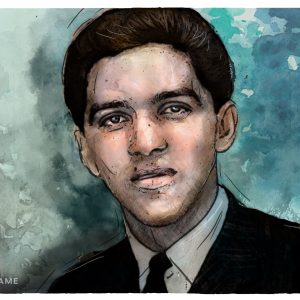

Goniwe’s life was inextricably linked to that of her husband Matthew Goniwe. The apartheid security forces abducted and murdered the school teacher and community activist along with Fort Calata, Sicelo Mhlauli and Sparrow Mkonto on 27 June 1985, while they were travelling back to Cradock after a United Democratic Front (UDF) meeting. Their burnt and mangled bodies were discovered days later at various spots along the Eastern Cape coast.

The murders drew huge condemnation of the regime in the press and among anti-apartheid activists in South Africa and abroad. The names and faces of the Cradock Four became symbols of the brutality of PW Botha’s government, but also of the power of activists to stand up to apartheid and cause its commanders concern when they realised that the centre would not hold for much longer. When the four activists were buried on 20 July 1985, tens of thousands of mourners and activists attended their funeral on the eve of the announcement of a state of emergency by the Botha regime.

The murders did not only remove four men whose community organisation and anti-apartheid activities had made the area increasingly ungovernable, they also made widows of four young women – Nyameka Goniwe, Nomonde Calata, Sindiswa Mkonto and Nombuyiselo Mhlauli – rendered nine children fatherless and left their families with unanswered questions about why, how and by whom the men had been killed.

Related article:

An inquest in 1987, held because of the high-profile nature of their deaths and public outcry, found that no one was to blame. It posited that they were the victims of political fighting within the anti-apartheid movement, between Azapo and the UDF.

Perhaps because her husband had been the most high-profile and targeted of the men who died, Nyameka found herself the unofficial leader of the widows who came together to support each other and fight for justice for their husbands.

When anti-apartheid newspaper New Nation published a top-secret “signal” from the Eastern Cape security police to the State Security Council calling for the “permanent removal from society” of Matthew, his cousin Mbulelo and Calata, FW de Klerk was forced to reopen the inquest into the deaths of the Cradock Four. This time it was found that members of the security forces were responsible, but none were named.

By the time the widows arrived in East London to testify before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in May 1996, they were “bruised … emotionally and physically” by their long search for answers, Nyameka told the commission. Initially, they were reluctant to participate in the process, saying they had enjoyed more publicity and official attempts to investigate their case than many other families, who they said should now have the opportunity to tell their stories.

Seven men applied for amnesty for killing the Cradock Four. “They have to show us remorse,” said Goniwe, “that they’re sorry for what they did. I don’t say that… I mean it would immediately make us happy … [But we will] grapple with that, inside, and it will take a long time. Healing takes a long time.”

Not just a wife

Goniwe was 34 when she went before the TRC, a social worker for the Social Changes Assistance Systems Trust (Scat) in Cape Town and the mother of two children. Her daughter Nobuzwe was born in 1975 and her son Nyaniso in 1982. By then, she had spent 11 years trying to find out what had happened to Matthew, longer than the 10 years they had been married. The security police disrupted her married years constantly and continued to harass the widows after their husbands’ deaths.

Goniwe was an activist, working towards achieving a democratic South Africa and a better life for all. She was born in Cradock on 3 June 1951 and when her mother died when she was three, her father sent her to live with her grandparents on a farm outside the town. She later moved to the township of Lingelihle, where she attended the Cradock Bantu Secondary School and was taught maths and science by a handsome, enthusiastic and righteously fiery young teacher named Matthew Goniwe.

After matriculating, Nyameka pursued a nursing qualification in Port Elizabeth. When she returned to Cradock for the holidays, she’d meet her former teacher. As she recalled in an interview with director David Forbes, who made a documentary about the Cradock Four in 2010, the two “met up and sort of fell in love, and then we were separated [because] obviously the distance … [But] we kept that contact through correspondence and phoning. It was a distant love relationship, but it grew over time.”

In 1975, Nyameka became pregnant and the couple married. They spent a few months together before and after the birth of their daughter Nobuzwe, before Nyameka left for Fort Hare University to study social work on a bursary. In 1976, shortly after the Soweto uprising, Matthew was detained and charged under the Suppression of Communism Act. After a year-long trial, he was sentenced to four years in jail. She described these years to Forbes as “very painful” and “some of the most difficult years of my life”.

The security police ensured that the young mother faced bureaucratic difficulties every year when she had to reapply for admission to the university. She told the TRC that during this time, her “biggest challenge … was to be available to my baby as often as possible, to attend to my studies and also to give support to my husband in prison. I remember that year [1976] being one of the toughest years I have faced in my life. I was short of money and had to rely on my brothers-in-law for assistance.”

Increasing scrutiny

When Matthew was released in 1981, he had missed four years of his young daughter’s life and returned to find his wife, having completed her degree, working as a social worker in Port Elizabeth. In 1982, he became the deputy principal at Nqweba Secondary School in Graaff-Reinet. But with another child on the way and his wife unhappy living in Graaff-Reinet, he transferred back to Cradock as the deputy principal of Semquale Secondary School.

Nyameka told the TRC that during this time her husband “was a brilliant maths and science teacher, but also a strict disciplinarian. These qualities earned him a lot of respect and praise in the community. His influence permeated all the schools in Lingelihle. His interest in the youth attracted the attention of the security police towards him. He was also seen as a person who took an active role in rekindling the politics of resistance.”

Related article:

Goniwe became increasingly active in local politics, establishing civic organisation Cradora and its youth wing, Cradoya, which brought him further scrutiny and harassment. When the apartheid government tried to use the then department of education and training to remove Goniwe from Cradock – by dismissing him from his post after he refused to transfer back to Graaff-Reinet – it led to a massive schools boycott. This resulted in widespread unrest and the six-month detention of Goniwe, Calata and others in a misguided attempt by the state to stabilise the situation. Instead, the detentions caused violence in the townships around Cradock to escalate, forcing the government to release Goniwe and his fellow activists, who were given a “hero’s welcome by the community”.

“The whole family bore the wrath of the security police, which took the form of harassment, early morning house raids, constant surveillance, death threats, short-term detentions for questioning, mysterious phone calls, tampering with cars, etc,” Nyameka told the TRC. One morning when Matthew was driving her to work, the head of the security police in Cradock, Major Henry Fouche, pulled the couple over and dragged Matthew out of the car, “pointed a gun at [his] head, shouting, ‘I’m going to kill you.’ We were then driven to the police station, we were both searched, bodily searched, and released later on. Matthew laid a charge against Fouche, which of course never came to anything.”

When her husband did not return from his meeting on 27 June 1985, Nyameka waited until the following morning before phoning the UDF activists Matthew had met. They said he and his three comrades had left Port Elizabeth at 9pm the previous night. “You can imagine the shock, and I shuddered to think what might have happened to the comrades,” she told the commission. Searches and visits to nearby police stations proved fruitless. Nyameka returned to Cradock to be told that the police had phoned and left a message to “inform the family that Matthew’s burned car had been found near the Scribante racing course outside Port Elizabeth. Immediately, we knew that something serious had happened.”

Nyameka had to tell the wives of the other men. As Calata’s son Lukhanyo told The Sunday Times newspaper, “Mrs Goniwe was the person my mother turned to after news broke that the bodies had been found. Their relationship was one of sisterhood, their relationship was one of love.” Nyameka also “alerted the press, the national media, international media and everybody of influence to try and put pressure on to the police authorities, or the government.”

Of the seven former security forces members who applied to the TRC for amnesty – Nic van Rensburg, Herman du Plessis, Sakkie van Zyl, Eric Taylor, Gerhardus Lotz, Eugene de Kock and Harold Snyman – only De Kock was granted amnesty, and he was not involved in the murders but in their cover-up. The commission ruled that the remaining officers had not made a full disclosure.

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) should have prosecuted them, in accordance with the TRC Act. But they and the Cabinet ministers – including De Klerk, Adriaan Vlok and Barend du Plessis – who sat in the meeting during which the Cradock Four’s “permanent removal from society” was discussed were never called to account.

A democratic devotion and betrayal

After testifying at the TRC, Nyameka committed herself to community development, returning to Cradock from Cape Town to help build the local municipality post-apartheid. She became the mayor of the Inxuba Yethemba Local Municipality in 2011 and served as its speaker from 2016 until her death.

Longtime friend Di Oliver told the Grocott’s Mail newspaper that during this time, Goniwe “was a loyal soul. She was gentle and caring and open and tried to always be very fair. Not always easy in a small town to be somebody who I think everybody loved, and I think everybody did like and love Nyame.”

Related article:

Executive municipal mayor Wongama Gela echoed this sentiment, paying tribute to Goniwe’s “humanity, respect and immense loyalty to the cause of her people. Her first concern was never for herself but always for her community, how she could make our district and her locality a better place for every family living there and every individual passing through.”

But there was a darker, more depressing side to Goniwe’s life as a result of her betrayal by the ANC. The political interference of high-ranking members in the prosecution of TRC cases exhausted and depressed her.

In May, Lukhanyo Calata went to court to compel the NPA to make a decision about prosecuting those responsible for killing his father, Goniwe, Mkonto and Mahlauli. When former TRC commissioner and Foundation for Human Rights executive director Yasmin Sooka phoned Goniwe to update her on the case, Goniwe “seemed quite despondent. She was quite tired, to be honest, at the fact that so many years had passed and there had been so little joy, really, in dealing with this issue.”

Related article:

Sooka said Goniwe seemed “so different from normal this year, from the upbeat person that was so full of fire and verve in wanting this case to go forward. I got the impression that she was really struggling and she felt quite betrayed, because I think she’d always thought that there would be a lot more commitment, really, on the side of this government to pursue the case. I think when I told her about some of the stuff that was emerging from the cases and that it was quite clear that there had been political interference, I think that was devastating for her and she didn’t expect it.”

Advocate Howard Varney, who represents the families of the Cradock Four, decried on Facebook after Goniwe’s death the fact that “to date, the president, ministers of justice and police, and indeed government itself, maintain their strict silence on the suppression of these cases”. Varney added that, “post-apartheid South Africa failed Nyameka Goniwe. We should all hang our heads in collective shame.” Forbes said Nyameka “spent her whole life pursuing justice and what’s really sad for her and the family is that she died without finding justice”.

Goniwe died in the town in which she was born, where she met and married the man she loved. The town where her children were born, to which she dedicated much of her life. It is home to a monument to the Cradock Four, a bittersweet token of cold comfort in honour of their contribution to the struggle for democracy. Goniwe is buried there now, but the quest for justice through the prosecution of the surviving men responsible for the deaths of the Cradock Four should not be buried with her.