Notes on gender-based violence and fear

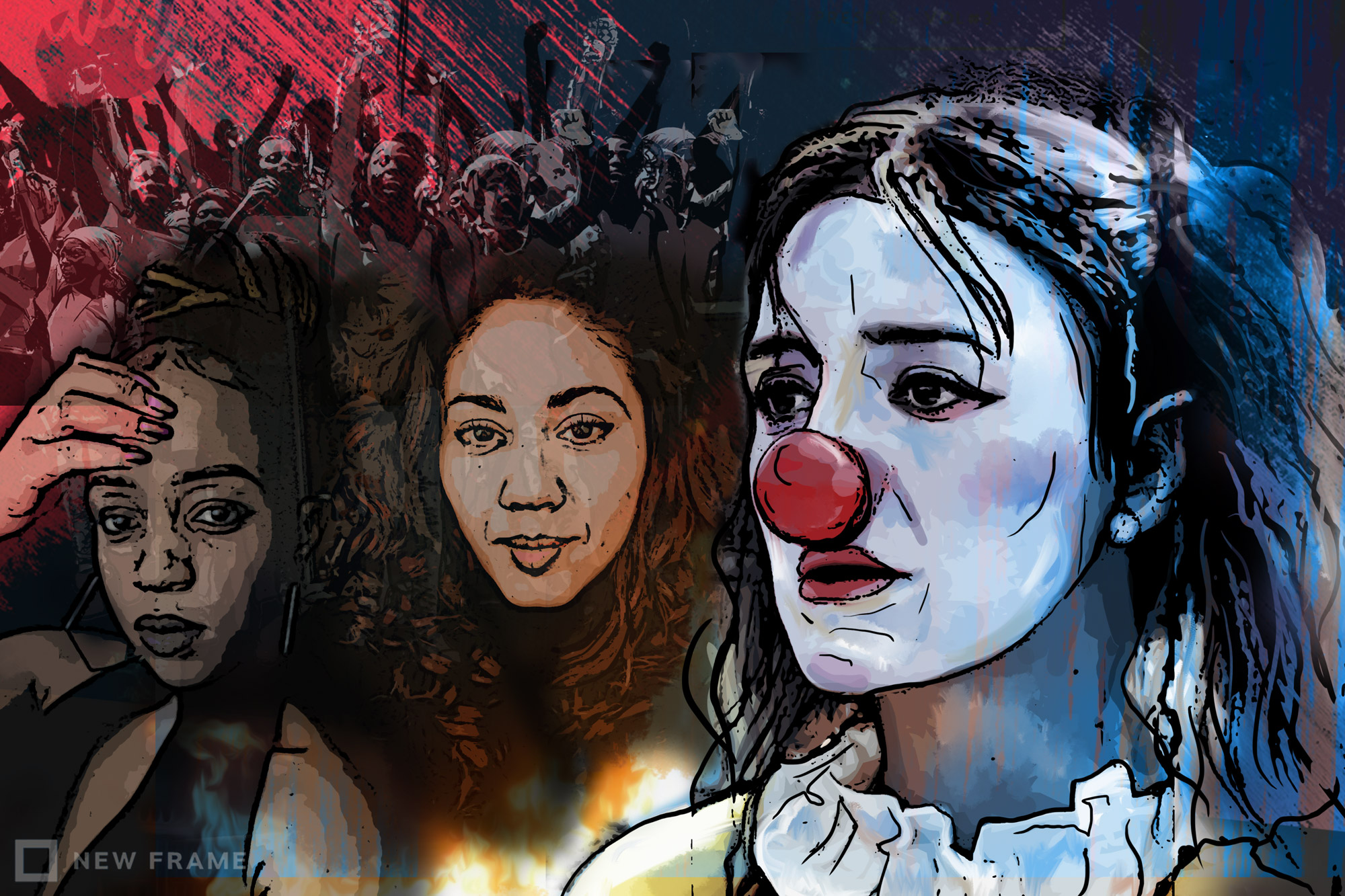

The murder of Precious Ramabulana, after news of violent repression and killings in South America, raises the simmering anger and fear among women and LGBTQIA+ people to boiling point once again.

Author:

29 November 2019

Gender-based violence is everywhere, in multiple forms. Women and the LGBTQIA+ community navigate the world deeply afraid and enraged. Their freedom of movement and human rights are restricted by the harsh realities of brutal repression, rape, assault and murder that accompany the many other violences that are a daily reality and threat.

According to the United Nation’s 2018 study on homicide, around 87 000 women and girls were murdered in 2017 globally. Hate crimes against LGBTQIA+ people have increased dramatically, largely in Latin America, which recorded four murders a day that year.

The study specifically acknowledges the killings of sex workers, indigenous women, queer women and women in war-related conflicts – intersecting communities that are deeply vulnerable.

In South Africa, at the meeting point of economic, social and cultural discrimination, the term “corrective rape” aims to try and capture the specific violence against LGBTQIA+ people in a transphobic and homophobic society and world.

Exact statistics are impossible to record for many reasons, including the fact that most cases are not reported. South Africa has particularly high rates of gender-based violence, staggeringly so, making it difficult to codify.

Brutal murders

Between 25% and 50% of women are estimated to have been subjected to some form of violence. According to the latest annual crime statistics for 2018-2019, 2 771 women were murdered and the number of reported sexual offences, mostly cases rapes, was 52 420.

At 2.30am on Sunday 27 November, Limpopo student Precious Ramabulana was allegedly raped and stabbed 52 times. The 21-year-old Capricorn TVET College student was enrolled on the Ramokgopa campus in Mokomene. The perpetrator allegedly entered through the window while she was asleep. Ramabulana’s unemployed mother survives on a disability grant.

There’s an imbalance in the public outrage and social media fury over Ramabulana’s cruel murder, for many reasons, in the wake of the boiling rage that surfaced following the rape and murder of 19-year-old University of Cape Town student Uyinene Mrwetyana in August.

Related article:

It is all too often that the murders, rapes and violence faced by poor, black working-class women and queer people go by unnoticed, ignored and forgotten. Similarly, women and the LGBTQIA+ community in marginalised communities in Latin America, the Carribean and Africa are disproportionately affected by sexual violence. Their access to justice and healthcare is limited or non-existent.

Response to protest

Women and LGBTQIA+ people on the frontlines of gender and human rights activism are likely to experience brutality, including sexual assault, at the hands of the police and military. As always, these are weapons of power used to frighten, humiliate, dominate and control. Such women and LGBTQIA+ people exist in a constant state of rage and fear, knowing they will have to face violent backlash and be ridiculed, discredited, ignored and disbelieved. This kind of activism is lonely and emotionally draining.

In Chile, young activist, street performer and mime Daniela “El Mimo” Carrasco, who joined the mass protest against inequality and a shortfall of social services, was found hanging shortly after she had been taken in by the police. Her death was not widely reported in international news.

Chile has been engulfed by violent protests, which began as mobilisation against transport fare hikes. At least 20 civilians have reportedly been killed. The police crackdown has been brutal. The National Institute of Human Rights in Chile says more than 1 233 civilians have sustained injuries. At least 688 of those had wounds caused by weapons. Thousands of protestors have been arrested.

Related article:

The police captured Carrasco on 19 October. The following day, her body was found hanging from a tree bearing signs of brutal abuse. Almost a month later, her family received the verdict of the official investigation: suicide.

While the events that led to her death are unknown, her family, the Trade Union of Actors and Actresses of Chile, the feminist collective #NiUnaMenos-Chile and countless public voices are demanding further investigation of her death. They are calling it a horrific murder and femicide. #NiUnaMenos-Chile sees the murder as a warning, meant to intimidate those, especially women, who are mobilising to protest against the national crisis in Chile.

The authorities deny any possibility of third-party interference or murder.

Storytellers

Carrasco’s death was followed a month later by that of photojournalist Albertina Martínez Burgos, who was found stabbed and beaten to death at her home in Santiago, Chile. The 38-year-old was documenting the repression of anti-government protesters at the time of her death, specifically violence against women.

It’s been reported that her recent photographs of the ongoing massive demonstrations against Chilean President Sebastián Piñera have been stolen. According to the Coalition for Women in Journalism, she is the sixth journalist to be killed this year.

To mark the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women on Monday 25 November, demonstrations were held in Mexico and Latin America.

In Mexico City, demonstrators marched through the streets calling on authorities to do more to combat the high rates of femicide and rape in the country.

In Chile, they marched with red hands painted over their mouths. In Argentina, they used purple paint. And in Uruguay, they marched in black.

Related article:

In Honduras, they hung stuffed animals from ropes in honour of murdered women, while in Panama City, women lay under sheets covered in fake blood to represent those who have been killed.

Women in Sudan chanted, “Freedom, peace, justice”.

16 Days

In South Africa, we are in the first week of the country’s annual 16 Days of Activism for No Violence against Women and Children campaign, in line with the United Nations’ international 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence campaign. In response to the ineffective campaign, non-profit organisation Sonke Gender Justice launched its own campaign, #BeAccountable.

Sonke says that “through examining the role played by various state institutions, the criminal justice system, institutions of higher education, the media and civil society organs, our #BeAccountable campaign aims to highlight the importance of a culture of accountability amongst those who have an obligation or responsibility to promote and realise human rights”.

The insincere response from the South African government, in particular, to urgent requests to address the crisis of gender-based violence is alarming.

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s emergency action plans have been highly criticised. In October, he called for an urgent joint sitting of the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces to discuss the government’s plan to tackle gender-based violence – the direct result of relentless, multiform activism by South Africa’s women and LGBTQIA+ community, not only this year but over time.

Ramaphosa has committed R1.6 billion to programmes to tackle gender-based violence and has promised to focus attention on access to justice, strengthening the criminal justice system, rolling out educational programmes at schools and in communities, and to creating jobs for women vulnerable to abuse.

Before, not after

Deputy head of the department of social world Marichen van der Westhuizen and deputy head of the department of social work Glynnis Dykes, both at the University of the Western Cape, wrote a response to Ramaphosa’s plan, in which they say “none of these interventions will work unless government and civil society work together. Non-governmental organisations should be supported to develop their services further. Above all else, the government needs to make sure that the South African Police Service, court system, correctional services, social development, health and education are reformed.”

They are correct.

Ramaphosa has recognised the violence as more than a national crisis and repeatedly promised to tighten the law. But tougher laws and harsher sentencing is not a sustainable solution as it seeks to deal with the aftermath of the violence. Rather than prevent lifelong trauma, it aims to address the fallout with poorly resourced state institutions, inadequate police training, a severe lack of empathy for survivors and a lack of recognition of the deeply systemic nature of gender-based violence and the way it is infused in institutions, social beliefs and culture.

Related article:

A study by American law firm Farah & Farah, titled The Sexes’ Sense of Safety, finds that women are highly concerned about their safety when going about largely unavoidable daily acts such as jogging, walking at night, walking to their cars at night and using an elevator or stairwell in public spaces. Notably, women more so than men hold their keys between their fingers while walking alone and have a plan to escape their home in case of a violation.

This is a global phenomenon. The rights of women and LGBTQIA+ people is about more than just challenging gender rights. It speaks to the violation of the basic human right to feel safe when walking alone, crossing the street, occupying an empty stairwell, being home alone or being in any space alone with men.

Ramaphosa’s action plan requires serious thought about how the government intends to formulate sustainable, urgent and practical interventions that create safe spaces and engender a feeling of safety among South Africa’s female and LGBTQIA+ populace – and further to that, implementable interventions beyond those existing in policy.

Rape: A South African Nightmare author Pumla Dineo Gqola wrote recently: “I want to live in a country and world where women do not have to be fighters just to stay alive. Like millions, I may be exhausted from the fight and raw from the spilling of so much blood and breaking of so many spirits, but we will not tire. Asoze aphel’ amandla. We will continue to craft consequences that count. On our own, together, we are finding a way out of fear.”

Women and LGBTQIA+ people are exhausted, enraged and constantly afraid. It’s no way to live.