Norman Sekgapane and North West boxing

The legacy of the first South African boxer to fight in a multiracial bout at home during the height of apartheid mirrors that of his province. Once boxing royalty, they are now not even an afterth…

Author:

27 January 2020

When he entered the Mmabatho Independence Stadium to challenge Colombian Antonio “Kid Pambele” Cervantes for the World Boxing Association (WBA) title in 1978, Norman Sekgapane – though no regular boxer – was long past his prime.

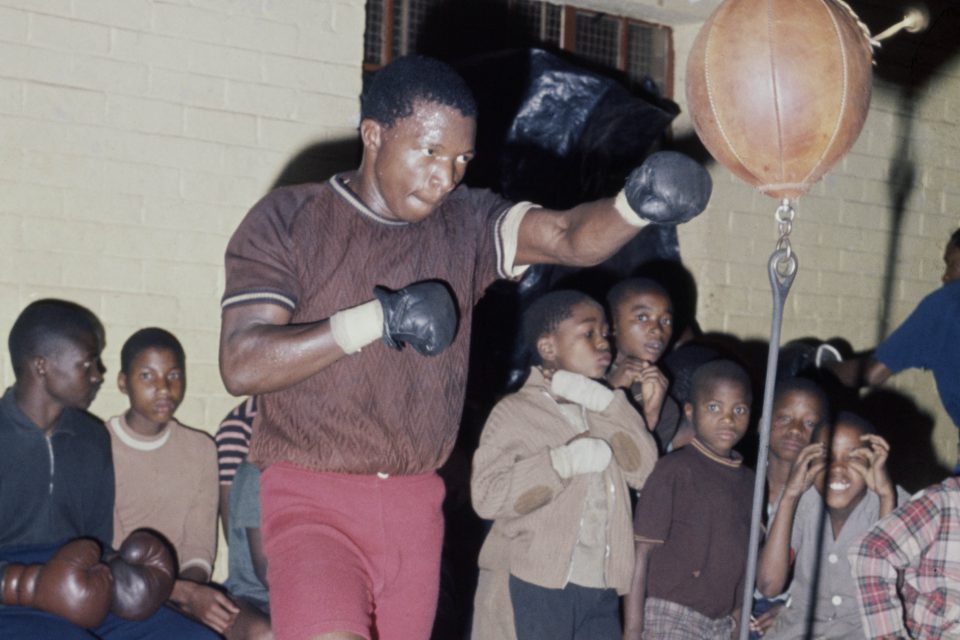

But it would take nine rounds for Cervantes to confirm this. More than being his swan song, the clash against Cervantes would be a fight that immortalised Sekgapane as a symbol of resistance. As the first black boxer to fight in a multiracial match – against Denmark’s Jorgen Hansen in 1974, whom he knocked out in the ninth round – Sekgapane’s fists had as much meaning outside the ring as they did in it.

He was black South Africa’s great hope, the very essence of resistance sports, some would say. His fists were loaded with the hopes of a large section of society and every punch was a righteous act of rage. But what Sekgapane symbolised was of little concern to Cervantes, who was already living out his legendary status as one of South America’s greatest pound-for-pound fighters.

Idaho’s The Times News reported that in preparation for the fight, Cervantes was sparring with only his left arm, reasoning that he would not need to use his right. That by the time he decided to use his right arm, the fight would be over.

“When he whips out that right, Pangaman will be in trouble,” his sparring partner, Pierre Jacy Fourie, told the paper.

Related article:

Cervantes had made a name by challenging fighters on their home turf and fighting them as though they had invaded his living room. In 1971, he forced Argentinian Nicolino Locche into a 15-round dance to defend his world junior welterweight title. But in front of an 8 000-strong Mmabatho crowd, he would first have to understand why the word “panga” evoked so much fear in South African streets.

In its most liberal use, a panga is an effective farming tool. But in the hands of feared neighbourhood pantsula, it is a deterrent before it’s a weapon. Sekgapane’s swift uppercuts embodied its sharpness and evoked its fear, and earned him the moniker “Pangaman”.

Ghanaians and Nigerians knew him as “The Spoiler”, having defeated highly rated boxers such as Ghana’s Joe Tetteh and Nigeria’s Jonathan Dele in a single year. Though he gave as much as he took in his fight against Cervantes, Sekgapane found himself struggling to stand in the ninth round after a straight punch to the head landed him on the floor.

It was in that moment that Sekgapane transcended the ring and became something of a martyr: a symbol of resistance against the unjust boxing culture black fighters had to endure as he held his own despite only getting this big chance past his prime.

Letting his fist do the talking

Sekgapane was known for his quietness. When the time came to speak about one of the biggest fights of his life, the country’s first multiracial bout, he let his training partner and former world light heavyweight champion – American Archie Moore, who had travelled to Johannesburg to assist Sekgapane – do the talking. And at a pre-match conference, he said that the fight would be a lesson.

And if there was a lesson in that fight it was that, in the absence of the systematic cushioning they received from the apartheid government, white boxers were also mere mortals and they, too, could bleed.

A year after his defeat to Cervantes, in an act of poetic justice, Sekgapane would watch as American Big John Tate plucked out the hearts of white South African boxing fans at Loftus Versfeld when he defeated Gerrie Coetzee in a 10-round wrestle for the WBA heavyweight title vacated by Muhammad Ali. No one thought of it as a mere fight between two talented boxers. What Tate did was to strike at the very heart of whiteness.

When Sekgapane looked back over his boxing career, he hoped history would be kind to him and that he would be remembered as a man who tried despite the barriers he had to pass through.

“Every time they have to think about boxing in 10 to 20 years, they will also remember me. They’ll mention my name. [They’ll say] this is the man who was the first fighter to fight in a multiracial match [in South Africa] and the first black boxer to fight the world title,” Sekgapane said in one interview.

An unheralded champion

Sekgapane was also the first South African boxer to hold both the junior middleweight and middleweight titles, then the country’s premier titles. It’s a feat many of his white peers struggled to achieve despite favourable conditions. When he retired in 1981, he had 51 wins, two draws and only 15 losses to his name. But despite his achievements and his fight to level the playing field, little is known of Sekgapane. It is the tragic tale of most boxing legends whose contributions are hardly ever remembered and which also reflects the state of South African boxing at large.

“The one thing we lack as boxing fraternities in North West is the appreciation of our legends, to acknowledge their contribution to the sport and the trail they’ve blazed for upcoming fighters,”

says North West University Boxing head coach Onalenna Tsae.

Sekgapane’s involvement as a judge, mentor and later as a member of the Boxing South Africa (BSA) board was not enough to endear him to a younger generation of fighters and fans. His legacy continued to live in obscurity. In an attempt to honour Sekgapane and revive boxing as a popular sport in the province, the North West provincial government assisted the Norman Sekgapane Foundation to stage the Norman Sekgapane Boxing Extravaganza in 2015 in his hometown of Mahikeng.

Related article:

However, attempts to honour Sekgapane’s legacy have failed simply because they don’t happen in isolation from the general state of boxing in the province, which has been in a perpetual state of decline since the collapse of Bophuthatswana in 1994.

Sekgapane’s story leads us to ask: What happened to boxing in North West? Once considered the “Las Vegas of South African boxing”, with the Sun City resort hosting some of the most pivotal fights in the sport’s history, what unforgivable sin did boxing commit in the north?

The crisis of boxing in North West is the crisis of the sport everywhere in the country. The boardroom politics of both national boxing bodies, the South African National Boxing Organisation and the BSA, continue to overshadow and disrupt issues of development and promotion of the sports at regional level.

Another issue at the heart of the decline of the sport in the province is financial mismanagement and corruption. This was highlighted by the case of Stanley Motsuenyane, whose Bamboo Tree Productions stages several amateur tournaments around the province. Motsuenyane lost a R450 000 sponsorship from the gambling board, three months after signing it. He alleges he lost the sponsorship because he refused to pay a R200 000 kickback.

Way forward

Despite the many challenges boxing continues to face, Tsae says there is hope.

“North West is gradually growing. Our provincial teams are starting to perform better in national championships. We are not where we are supposed to be, but we are surely in the right direction,” Tsae says.

“The relationship between the North West Provincial Sport Confederation and the department of sport also has played a vital role in growing boxing, to an extent that the province is hosting tournaments more frequently through their affiliated clubs as compared to previous years.”

Even with these challenges, boxing remains an integral part of working-class communities across the province. The youth view the sport as more than just a recreational activity, they see it as a way out of poverty. It was, in fact, Sekgapane’s vision to see boxing become the liberatory song of young working-class men and women.

The fulfilment of that is playing out at several ametuer boxing clubs across the province, such as the Khuma United Boxing Club, which produced the talented Mawande “Rambo” Mbusi. In Marikana, the sight of what is considered post-apartheid South Africa’s worst crime, you will find another significant club in the form of the Marikana Boxing Club, which is home to Onke Khanzi.

Related article:

“The most important part about amateur boxing is that it gives boxers foundation experience to turn professional,” Tsae says.

The announcement of Sekgapane’s death in 2018 was met with shock. But more than being a reaction to the untimely loss of life, this shock was also an expression of the realisation that an enduring symbol of the province’s contribution to South Africa’s boxing fraternity and boxing’s historic defiance had died.

North West has consistently struggled to produce a boxer of Sekgapane’s stature. And if the province stands a chance at ever producing a boxer even half as good as Sekgapane, that chance lies in amateur boxing.

Perhaps Sekgapane sits somewhere in heaven not far from Ali or Baby Jake Matlala, and is looking down and marvelling at the efforts of youngsters in amateur boxing clubs across the province to get it right. Or perhaps he’s dismayed at the chaos that continues to engulf and define the sport in general.