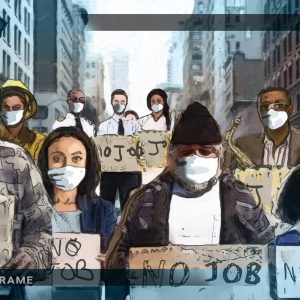

No wonder the people are suspicious of the state

South Africans have no reason to trust a government that has forsaken them throughout Covid-19 and seems wholly unmoved by their economic plight.

Author:

10 December 2021

After two devastating years that decimated the lives and livelihoods of millions of people, South Africa has not learnt the lessons from global public health and economic responses to a once-in-a-century pandemic and recession.

During 2021, the country reeled from the effects of two deadly variants. The premature withdrawal of an inadequate fiscal stimulus and the implementation of an over-the-top lockdown that did not allocate a cent towards relief for millions who would suffer from its ruinous impact contributed towards the July riots, which resulted in 342 deaths and wreaked havoc on the economy.

An unprecedented 1 122 hours of load shedding by 20 November, including during the week of the municipal polls, impeded the economic recovery. The ANC’S electoral support fell to 46.1%, with 54.4% of eligible voters deciding to stay home.

Related article:

As South Africans tried to imagine a post-Covid future, the new Omicron variant arrived. It has become the dominant variant and appears to be highly infectious, though the severity of infections remains unclear. But it has resulted in increased uncertainty about the pandemic’s trajectory and the country’s prospects for economic recovery. The only certainties are that the economy will revert to its pre-pandemic trend of low GDP growth in 2022 and that the national unemployment rate will increase to more than 50% before the 2024 national elections.

After 12 “family meetings” in 2021 during which President Cyril Ramaphosa adjusted lockdown restrictions and reported on the rollout of vaccines, South Africa has intersecting public health, humanitarian and economic crises. On 8 January, daily new infections peaked at 21 980 as the Beta variant triggered a second wave throughout the country. There was relative calm from February until May, when infections started to increase again on the back of the more transmissible and deadly Delta variant causing a third wave of infections. On 3 July, daily new infections peaked at 26 485. They were low during October and fell to less than 300 during the first two weeks of November, when they started increasing again owing to Omicron. Now we are in the fourth wave of infections.

Nothing to show for lockdown

South Africa implemented one of the harshest lockdowns in the world in 2020, but there is little to show in terms of improved public health outcomes. This past week, South Africa was edging towards a total of almost 3.1 million cases, the 18th highest in the world and the highest on the continent. It had 90 038 deaths by 8 December, the 15th highest in the world.

According to the South African Medical Research Council, by 4 December the country had 275 976 excess deaths over the pandemic period. South Africa’s excess deaths of between 380 and 390 per 100 000 people are the 14th highest in the world, The Economist says. The Lowy Institute in Australia produced a Covid performance index that ranked 116 countries across six indicators on 13 March 2021. South Africa was ranked 86th. Rwanda was ranked seventh. There now seems to be a consensus that the lockdown did not flatten any curve. It only delayed it by two or three weeks.

The National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey has shown the extent of the country’s humanitarian crisis. It found that 10 million adults and nearly three million children were in a household affected by hunger during April and May 2021. Women were more likely to shield children from hunger, the survey said.

Related article:

The National Treasury’s response to the crisis was a R264.9 billion austerity budget in February for the three-year medium-term expenditure framework (MTEF) period until 2023-2024. It included cuts of R50 billion (health, in the middle of a pandemic), R39 billion (police, including the retrenchments of 18 000 officers), R36 billion (social grants), R25 billion (basic education), R24.6 billion (tertiary education) and R15 billion (defence).

The government ended the R350 a month social relief of distress grant at the end of April. On 30 May, Ramaphosa increased restrictions to adjusted level two. There were no stimulus measures to counter the effect of the lockdown. Five weeks later, the July riots started. The South African Property Owners Association said the riots had an impact of R50 billion on GDP.

According to Statistics South Africa, GDP declined by 1.5% during the third quarter of 2021. The economy shed 660 000 jobs, which was equivalent to 88.9% of the 742 000 jobs that were lost during the first nine months of the year. At the end of July, former finance minister Tito Mboweni announced a R37.9 billion stimulus package, which included R26.7 billion for the reintroduction of the social relief of distress grant until the end of March 2022.

The economic cost of the July riots was far more than the savings from ending this grant. On 11 November, the National Treasury’s medium-term budget policy statement made upward revisions of R254.6 billion to expected budget revenues for the MTEF period owing to strong commodity prices. Almost half of this windfall (R120.9 billion) will go towards increased spending during the three years until 2023-2024. Therefore, the net effect is that the austerity measures that were announced in February have declined to R144 billion from R264.9 billion.

Bleak outlook for employment

Meanwhile, the Reserve Bank has started a new cycle of interest rate increases. After the recent 25 basis points increase in the repo rate to 3.75%, accountancy firm PwC expects further increases to 6.75% by the end of 2024. The combination of austerity and many interest hikes will result in an increase in unemployment.

After 27 years of economic mismanagement, South Africa’s GDP per capita in 2020 was only 16.1% higher than it was in 1994. By comparison, Malaysia’s GDP per capita has increased by 654.1% over the same period. Since the start of the lockdown in March 2020, 2.1 million people have lost their jobs. There are now 12.5 million unemployed people.

South Africa now has unemployment rates of 77.4% for youths, 51.1% for Africans, 55.6% for African females, 54.5% in the Eastern Cape and Limpopo, and 52.2% in North West. The national unemployment rate for people of all races is 46.6%. South Africa is now an unviable society. Will it take 13 million, 14 million or 15 million unemployed people for the government to decide that its failed economic policies can never work?

Related podcast:

Internationally, there is no country that had a perfect public health and economic response to the pandemic. For example, Brazil, led by the Covid denialist right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro, had a disastrous start and soaring infections and deaths. But the country implemented Auxílio Emergencial, a cash transfer programme, which paid $106 (R1 667) a month to 68.2 million people at a cost of $52 billion (R818 billion). It has now fully vaccinated 65% of its population.

Vietnam, which has a population of 97.3 million, was the envy of the world as it had only 7 600 infections and 53 deaths by the end of May 2021 without a lockdown. Its GDP grew by 2.9% during 2020. But the Delta variant overwhelmed its efficient public health measures. The country now has 1.4 million cases and 26 930 deaths.

Looking in the wrong place

South Africa’s public health failure was not to look east to countries that have mostly contained the virus over the past two years. According to Michael Baker, a New Zealand professor of public health, the elimination strategies adopted by China and Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand were more successful than those of countries in Europe and the United States that tried to suppress or mitigate the virus. South Korea, which is currently experiencing a spike in infections owing to waning vaccine efficacy among older people and unvaccinated children, is another success story.

Successful countries implemented many pandemic control measures, including public education using community health workers (Rwanda), targeted lockdowns (China), mass testing (United Arab Emirates), mass pre-emptive testing in areas that have outbreaks (China), providing free home test kits (US), contact tracing, case isolation, quarantines for exposed people, subsidies for people to isolate or quarantine, test and quarantine for international visitors, and the use of masks and other social distancing measures.

Related article:

A recent surge in cases in highly vaccinated European countries shows that vaccines alone cannot stop the virus, a CNN article says. South Africa has relied on a limited number of pandemic control measures, including lockdowns and vaccines. It inexplicably failed to invest a cent in training community health workers who could be involved in public education and contact tracing. It did not even try.

In an article for The Guardian, Baker and Martin Mckee say that it’s “the behaviour of governments, more than the behaviour of the virus or individuals, that shapes countries’ experience of the crisis”. Yann Algan, a French professor of economics, says research has shown that trust in both the government and scientists has been the main driver of citizen compliance with public health measures, including vaccine uptake.

Internationally, many countries invested in their people throughout the crisis. Global stimulus packages were worth $16.9 trillion, according to the International Monetary Fund. There were 734 cash transfer programmes in 186 countries, a paper by World Bank economist Ugo Gentilini and others found. If the South African government had invested in its people throughout the pandemic and before, and directed significant resources towards public education since the start of the crisis, there would be higher levels of public trust, participation in local government elections and vaccine uptake.