‘No-fee’ school is suffering from lack of funding

A lack of funding is placing an added burden on already-vulnerable parents, who must supplement underfunded children at a dilapidated school in rural Limpopo.

Author:

10 September 2018

The buildings of Vhulaudzi Secondary School in Matakani, near Makhado in rural Limpopo, are in such a state of disrepair, they are rotting.

The school principal, Mukondeleli Makwarela, and the school governing body’s (SGB) vice-secretary, Maria Ravhugoni, occupy a classroom that has been turned into a makeshift office. The room is divided into two parts with hardboard to create a cubicle for the principal and secretary, and what appears to be a waiting room.

The school has 605 learners, employs 23 teachers, and is fitted with three JoJo tanks and four taps to serve its water and sanitation needs.

On average, there are about 80 learners per class, double the number of learners regulated by government’s National Norms and Standards for School Infrastructure, which defines parameters for the basic infrastructure needs of schools.

These norms and standards state that all schools must have water, sports facilities, laboratories, security, functioning libraries, working toilets, electricity, and internet access.

Ravhugoni said overcrowding is a main concern for the SGB. “When there are many (inside the classroom), it becomes difficult for them to cope,” she says.

According to the principal, the school does not have a library. “They [students] do not know what a library is,” he says.

The state of the ablution facilities is so bad that New Frame witnessed students going into bushes to relieve themselves. Regarding this, principal Makwarela, 60, says: “The pit latrine toilets are not safe … at the back there are holes and the snakes can just enter, but we are trying.”

He adds that there are only 16 toilets divided in half for boys and girls which are supposed to serve all the school’s learners. “You can see that we are still owing learners toilets, serious toilets.”

Underfunded learners

According to Makwarela, learners are also underfunded. The school’s budget allocation per learner is R790, which does not meet the allocation amount as set out in the National Norms and Standards for School Funding.

Nurina Ally, the executive director of the Equal Education Law Centre, confirmed that this year, according to the school funding policy, the allocation in no-fee schools is set at R1 316, while quintile four schools receive R660 per learner and quintile five schools get R228 per learner.

The school funding policy establishes the amount of funds each school should receive for non-personnel costs.

According to Ally, the aim of this policy is “to ensure that schools in poorer areas receive more funds”. She adds that non-personnel costs include textbooks, stationary, infrastructural maintenance and other school expenses.

Makwarela says the underfunding at the school makes it difficult to conduct the day-to-day running of the school. An example of this, he says, is the window panes: “We have changed the half of the window frame into a zinc. The lower half is patched with a zinc and upper it’s your glass.” This is done as the school fails to maintain the broken windows.

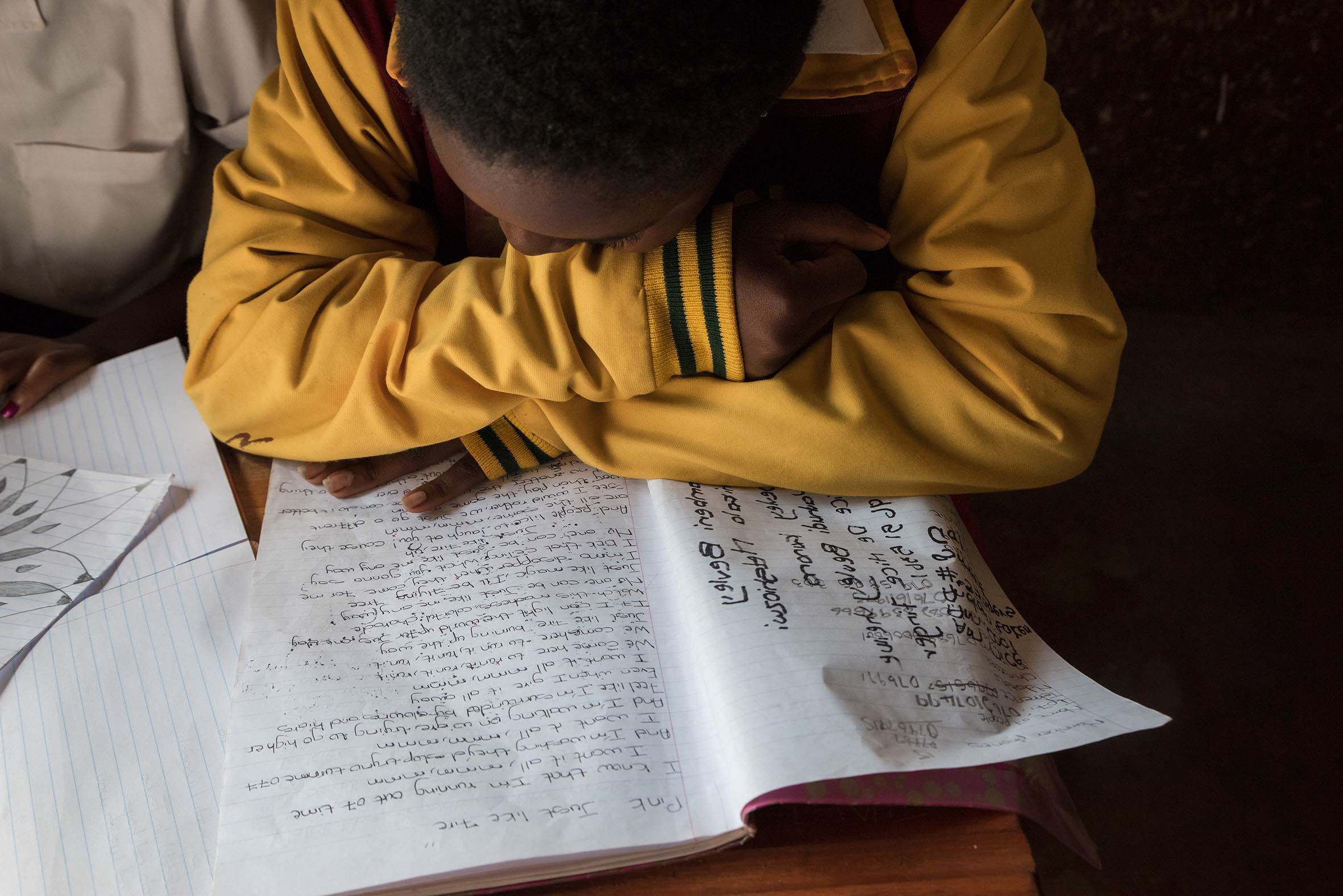

Underfunding has also resulted in a shortage of textbooks, which affects teaching and learning as teachers are unable to cover the entire curriculum, as much time for teaching and learning is spent writing down notes on the blackboard for learners to have access to the content in the absence of the prescribed textbooks.

“A below-average [class] – that’s where you are going to lose a lot of teaching time. Because you’re writing notes while they are copying. By the time they’re done, the period is over … next day, you are required to explain the notes, time is moving.”

At times, teachers need to make photocopies of exemplary papers and other learning materials, which has led to the school running out of stationery. Despite his staff doing their best, Makwarela says students must be supported.

The underfunding of learners has also led to asking parents for contributions of R100. The principal says asking parents for contribution is risky. But as the school is a quintile two, no-fee, school, parents object. “We survive because of the donations from parents,” he says.

The nine vendors who sit under a shade at the back of the school are each expected to fork out R50 for selling inside the school every month. These vendors sell fruit, bread, porridge and sweets at the school. The money from parents and the vendors is used to employ the school’s security guard and pay for stationery, says Makwarela.

According to Ally, the national school funding policy is intended to ensure redress and equality by affording more per student spending to no-fee schools. However, underfunding impacts the poorest learners in no-fee schools the most because no-fee schools are not able to raise more funds through fees.

In addition, according to Ally, “some provinces, particularly rural provinces, fall far below the per learner target for the year with more funds being allocated to personnel costs [salaries for teachers, principals and administrative staff]”.

Ravhugoni indicates the difficulties presented by underfunding in that it slows down teaching and learning. This, in turn, places an added burden on parents as many of them are unemployed and depend on welfare grants.

In 2016, Makwarela learnt that his school was number 26 on a list for a rebuild, after an enquiry, the school’s name could not be found on the list.

He explains that surveyors from the Department of Basic Education have been at the school more than 10 times. “There were people who came here indicating that the school deserve to be demolish,” he says.

The spokesperson for the Limpopo Department of Education, Sam Makondo, told New Frame the department will do its own investigation to verify the information. “It is important that we get all the facts because to our knowledge all Limpopo schools receive 100% of their norms and standards.

“I do not think we should have a school like this when we are celebrating over 20 years of democracy. That is also surprising if we can talk about we are free, and there is free education, while the infrastructure is so dilapidating.”