Izakhiwo ezitsha, iingxaki ezifanayo kusapho lwaseKhowa

Iminyaka emva kokuhlala kumzi odilikayo, usapho lakwaMbundana lwafuduselwa kwizakhiwo zethutyana ezathi ekubeni zingenambane zabe zisafana nqwa! nezo basuswe kuzo. Ngoku, olu sapho lunyanzelisa nge…

Author:

7 September 2021

A family in Khowa, Eastern Cape, whose derelict home collapsed last year, fear they will suffer the same fate in their new temporary residential units. These new units are so flimsy that they may not be able to withstand the weather much longer.

In January 2020, New Frame reported that the Mbundana family of Khowa in the Sakhisizwe local municipality had, for 28 years, been living in an abandoned, derelict and sewage-flooded two-room former clinic.

Despite being added to the housing waiting list several times over the years, the Mbundana family had been left in the condemned building with its crumbling walls, large gaps between the doors, walls and ceilings and no flooring.

Related article:

When the building finally collapsed around them in September 2020, the municipality provided the family of about 12 people with three temporary residential units. These units, measuring between 24 and 30 square metres, generally cost R64 441 each to erect and have a life expectancy of just 10 years, while a 40 square metre permanent-brick RDP house costs around R116 000.

“The government is wasting a lot of money on these units instead of just building houses. When they moved us, they promised that maybe after six months they will build us houses, but until now they are still quiet,” said Patricia Mbundana, 25.

Fancy, but still shacks

Even though the family has more space than before, as they now share a total of six rooms, it does not mean their living conditions have improved. The temporary structures have no ceilings and shake in the wind.

“It is not even a year that we have been in these units and you can see they won’t last. We cannot lock the door. The rain flows in through the bottom and pools on the floor. It is very cold and frost collects inside at night and then melts into water running down the walls in the day,” said Mbundana, who lives with her mother Lindiwe Mbundana, 56, and her four children in one of the units.

The other two units house Lindiwe’s sister Nonkoliso Mbundana, 53, her daughter Khayakazi Mbundana, 29, and her three children.

Each unit has only two rooms with no bathroom, taps, toilet or electricity. They share an outside communal tap and use their neighbour’s outside toilet.

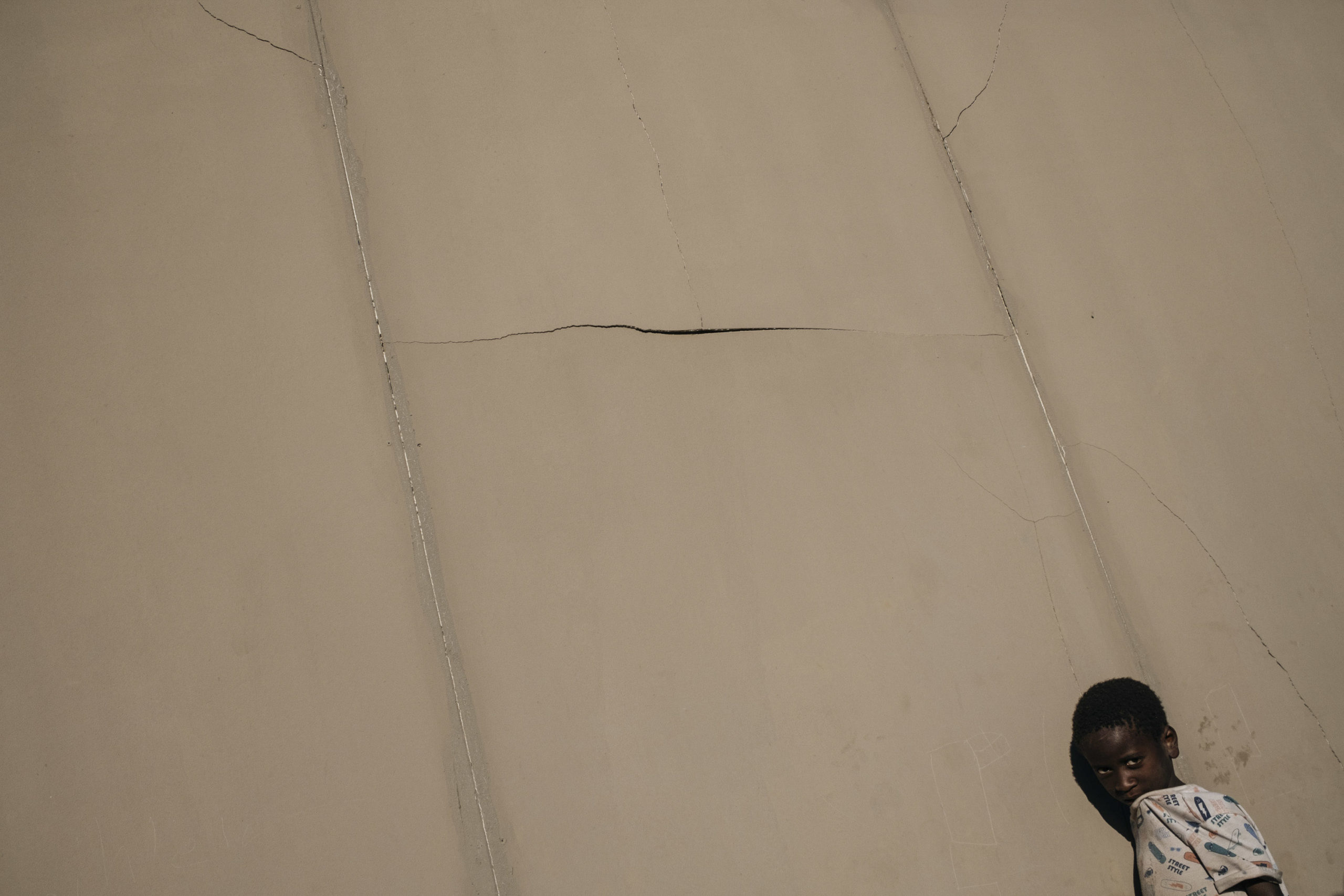

“You see this?” said Lindiwe Mbundana, pointing to some cracks in the wall. “When it is hot the house expands and when it is cold it contracts. So there are cracks on the outside and inside.”

The walls of the units are so flimsy that nothing can be hung on them. The municipality said it was unable to mount electricity boxes anywhere and that the families should ask their neighbours for electricity.

“Our neighbour has agreed. We use an extension cord and pay R50 per month,” said Lindiwe Mbundana. But this means the only appliances the family can have are a two-plate stove, kettle and a phone charger – no fridge or television sets.

Temporary solutions to permanent problems

Marie Huchzermeyer from the University of the Witwatersrand’s school of architecture and planning said the temporary units were being rolled out as a Covid-19 response to congested shack settlements, and were “essentially two-room Wendy houses or containers”.

“They are justified as an emergency response, but this case does not sound like an emergency, rather a long-standing problem. The household probably applied for an RDP house many years ago and has made the municipality aware of the problems for a long time,” said Huchzermeyer.

“If all the municipality can do at this stage is provide a temporary structure, then the household needs to know for how long it will be staying in that structure and what plans are being made in the meantime. Unfortunately, even in the most capacitated metropolitan municipalities, upgrading projects involve extensive delays and, realistically, a household might have to endure temporary structures for several years,” Huchzermeyer said.

Asked about the Mbundanas’ fate, Khowa Advice Office paralegal Babalwa Metzlar said, “There is no feedback from the municipality in terms of the way forward for the Mbundana family. My worry is that sometimes in summer there is torrential rain here. If you are living in a structure that is already broken, you are highly likely to be flooded inside.”

To make matters worse, one of the temporary structures is already partially destroyed.

Because the municipality did not remove the ruins of the old building, there was not enough space to fit all three temporary units on a single site. One unit was installed about two metres away from the house of a neighbour, which later caught fire and burnt to the ground. This fire licked off much of the outer wall and some of the thin insulation of the Mbundanas’ temporary unit, leaving nothing but a thin shell behind.

Sewage problem persists

The Mbundana family’s home is located at the foot of the Old Location township. It is an area built on a steeply sloping piece of land. Sewage routinely bursts out of faulty pipes and pours into the houses at the bottom of the hill, forming large pools. This has been happening for many years.

There seems to be no end in sight to this sewage problem.

Bulelwa Ganyaza, senior manager of communications at the Chris Hani district municipality, which incorporates Sakhisizwe, said the municipal sewer-networks team is “constantly unblocking and replacing clogged pipes” whenever there is an eruption of sewage in Old Location.

She said the municipality began replacing broken pipes in 2019. This work is still continuing.

Related article:

“However, the main issue making the situation worse is that houses were built on top of a sewer line. Our operations and maintenance team is on high alert monitoring the area using jetting machines and/or rods where necessary,” said Ganyaza.

But Metzlar said the pools of sewage have never been successfully removed and are a permanent feature of the township.

“The sewage [spill] is actually getting worse. You can see that it is running like a river here today,” Metzlar said.

It is not clear when the Mbundana family will ever be given proper houses. Sakhisizwe municipality spokesperson Nothando Sorasi promised to reply to questions in this regard but never did.

In early August, local media quoted Chris Hani district mayor Wongama Gela saying there were “more than 1 200 families using temporary shelters in the district”, some for over 10 years.

Gela said that because temporary units cost a lot of money, the municipality has decided to provide only serviced sites in future. Families will have to erect their own shacks.

This is despite the Eastern Cape government failing to spend R338 million of its housing budget last year. The funds had to be diverted to other provinces.

As things stand, the government does not provide services to each temporary residential unit. Department of Human Settlements guidelines state that one tap must be provided for every 25 families and one communal pit toilet for every five families. The guidelines are mum on the provision of electricity.