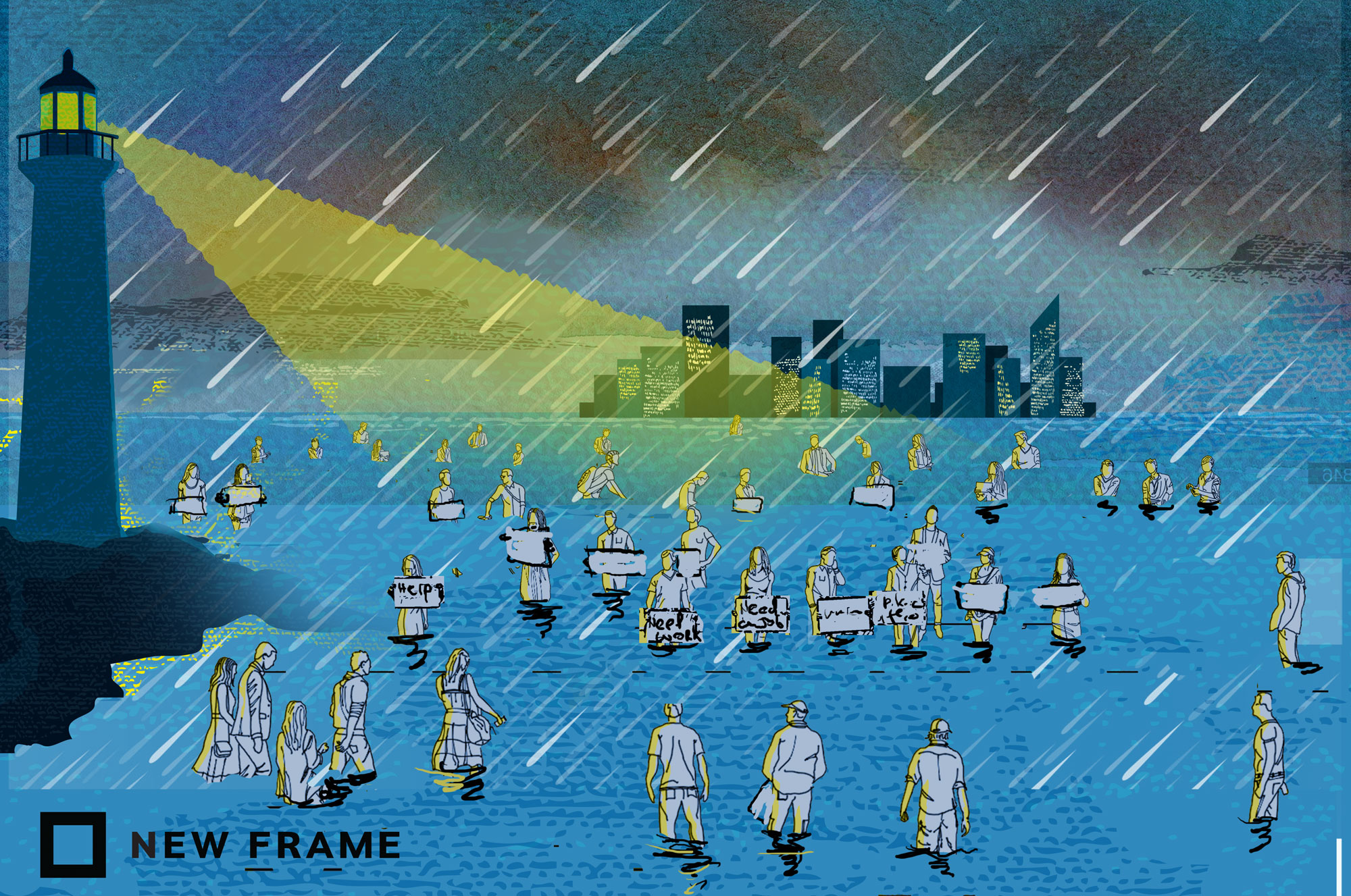

New data destroy hope of any jobs ‘bounce back’

One million new job seekers trying to enter South Africa’s post-lockdown labour market have driven unemployment numbers to record levels.

Author:

25 February 2021

Figures released earlier this week by Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) show that unemployment has reached unprecedented levels after around a million people were driven into a labour market that has no room for them.

While there was a slight increase in the number of people employed in South Africa since the end of September, the number of unemployed people increased by considerably more. Around 6.5 million people were unemployed at the end of September. That number had grown by more than 700 000 by the end of the year, leaving some 7.2 million without a job.

The increase drove the country’s official unemployment rate to 32.5% and was the most dramatic since the national statistics agency began collecting this data. It has taken South Africa from the frying pan of already world-leading unemployment and into the fire of a jobs market that will leave a generation scarred.

Stats SA’s report comes a week after the third wave of the National Income Dynamics Study – Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (Nids-Cram). The Nids-Cram data, which suggested that the percentage of people employed in October 2020 was comparable to pre-pandemic levels, had created some hope of a stronger labour market recovery and led some to prematurely herald a jobs “bounce back”.

Related article:

The considerable discrepancy between the two sets of data, which is likely down to sampling errors or basic differences in what the surveys were measuring, has not yet been fully explained.

The Nids-Cram data did show, however, that what recovery there was in the jobs market was deepening inequalities, rather than addressing them. Men and people with higher education levels were more likely to get jobs than women and those with lower levels of education. The data also showed considerable churn in the labour market, with many of the jobs recovered going to people who were not working before the hard lockdown.

A new kind of unemployment

Two key pictures emerge from the figures released by Stats SA.

The first shows that the labour market has mounted a muted recovery by adding just more than 300 000 jobs to the economy. With the lockdown having been eased to level one for most of the last quarter of 2020, many were expecting a slightly stronger recovery. “This is a much soberer scenario than we were expecting,” says Murray Leibbrandt, the National Research Foundation’s chair in poverty and inequality research.

The second relates to how ordinary households have responded.

Perhaps the report’s most significant figure may be the seismic drop in the number of people who were neither employed nor looking for work, who Stats SA categorise as “not economically active”. So, nearly a million people who were not looking for work at the end of September were actively trying to find jobs three months later by the end of December.

The economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic and resultant lockdowns appears to have driven many people who were not economically active to look for work. These new entrants to the labour market suggest that a massive effort has been made by South Africans to reorganise their lives in order to make some money. The market’s failure to accommodate that effort is likely the main reason for the unprecedented increase in unemployment.

Related article:

While the growth in unemployment during the first three quarters of 2020 was largely due to jobs lost as a result of the national lockdown, the fourth quarter rise was likely down to the almost one million new people trying to find a job in a market with room for only 333 000 of them.

Leibbrandt says that rising unemployment driven by new job seekers reveals the changing nature of the country’s labour market. “A huge adjustment is happening under our noses,” he says.

“It’s a fiction if you think that the labour market is adjusting to soak up these people looking for employment,” Leibbrandt says, adding that, more than ever, it has become the state’s “moral obligation” to provide impoverished households with greater income assistance. But it seems unlikely that obligation will be met after finance minister Tito Mboweni this week announced cuts to the budget for social grants over the next three years.