New Books | Women fighting for their power in SA

The Federation of South African Women was founded at a time when women were not considered important participants in politics – then 20 000 of them marched on the Union Buildings.

Author:

9 August 2021

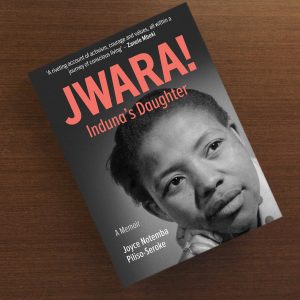

This is a lightly edited excerpt from You Have Struck a Rock: Women Fighting for their Power in South Africa (Kwela, 2021) by Gugulethu Mhlungu.

The Federation of South African Women and a history of women’s activism

“When we fight about narrative capital – the ability to generate and tell our own stories – we’re not just fighting about who gets to be in front of a camera, we’re talking about whether Black women’s lives have meaning to people.” – Kimberlé Crenshaw

The Women’s Day march of 1956 is often framed and discussed as a singular moment of women’s resistance and participation in the politics of apartheid South Africa. It speaks volumes that in the calendar of commemorative days only one is designated Women’s Day and, even as we mark that day, we discuss and know very little about what happened before and after the march. The activism by women who tried to change the status quo – the crime against humanity that was apartheid – has gone unreported and is poorly archived. We don’t speak enough about the Women’s Day anti-pass march as being one of the biggest anti-apartheid demonstrations, thereby downplaying the significance of the event. Even in the archiving of “big” movements such as the armed struggle, the student uprisings of 16 June 1976, and the pass law demonstrations in Sharpeville and Nyanga, a record of women’s involvement is lacking. Women’s names are not said enough – women who were at the coalface of making South Africa ungovernable in the 1980s, who waged war in their homes by insisting they work and live in urban areas, by raising their children in the confined backroom spaces of suburbia.

Related article:

The consequence of this poor archiving and memorialisation of women’s work and activism is not only that young women are deprived of their rich activist history but also that we do not realise that many of the gains of democratic South Africa are due to the women we fail to acknowledge. More importantly, we lose a gendered perspective of our history, which robs us of the ability to make sense of contemporary South Africa because, as Jacob Dlamini writes in his essential reading Askari: A story of Collaboration and Betrayal in the Anti-Apartheid Struggle, “Knowledge does not equal power, but power cannot be exercised without it … How, then, can South Africans exercise power as citizens if they have little knowledge of this part of their past? … Life is messy. But does the messiness of life mean that we should let apartheid’s secrets go to the grave?” Dlamini is referring to the sheer volume of information about the extent of apartheid’s crimes that was (and remains) concealed, or even destroyed. However, the same can be said of the dire lack of understanding of the patriarchal nature of apartheid, as well as the power systems of the past and present. This lack of a gendered lens, which is simply an accurate lens, does a great disservice to a country in which 51.1% of the population is female – as per the 2020 mid-year population estimates by Statistics SA.

When talking about the impact women had on effecting change in our country, a name that should come up, but rarely does, is the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw), founded in April 1954. It would have a huge and lasting impact on South African history in general, as well as on the moment when more than 20 000 women marched to the Union Buildings on an August morning two years after the federation was formed. In a 2017 paper titled “The family politics of the Federation of South African Women: a history of public motherhood in women’s antiracist activism”, Meghan Healy Clancy, an assistant professor of history at Bridgewater State University, Massachusetts, described the federation as “the first national organisation of women from all state-defined racial groups united against apartheid”. The establishment and existence of the federation was even more important because, until its formation, women were not considered participants or players in political organisations. To the state, the world and specifically to South African society, women were not equal to men, and their place was in the home. While white women had been granted the right to vote in 1930, for Black women the vote would come only in 1994. Furthermore, during the time of the resistance against apartheid, there was very little room in the formal political organisations for women. For instance, the ANC (founded in 1912) extended membership to women only in 1943, and the formal formation of the ANC Women’s League (ANCWL) happened as late as 1948. More broadly, even as anticolonial and pan-Africanist politics took hold all over the continent, the Pan African Women’s Organisation, the continent’s first women’s movement, was founded only in 1962. Although women had organised and worked endlessly, the political sphere remained a space dominated by straight men – a situation that provides the context for understanding the significance of Fedsaw.

Related article:

Most importantly, the Women’s Charter adopted at the Fedsaw inaugural conference influenced the 9 August march and the contents of the Freedom Charter, adopted by the South African Congress Alliance in 1955. Although its Women’s Charter focused on the plight of the oppressed Black majority, the federation was conceived of as a broad-based movement that would represent a wide range of women from across South Africa. The inaugural conference, held in 1954, was attended by 150 delegates from across the country, representing some 20 000 women. At the helm was a steering committee that included Lilian Ngoyi, Rachel (Ray) Alexander, Helen Joseph and Amina Cachalia, supported by prominent activists Sophia Williams-De Bruyn, Rahima Moosa, Dora Tamana and Florence Mkhize. Together, they provide a snapshot of the diversity the federation attempted to represent. It is fitting that, through short biographies, we pay tribute to some of these remarkable women, who played such a pivotal role in our history:

Lilian Ngoyi, who was born in Pretoria in 1911, was the daughter of a mineworker and a domestic worker. Before becoming involved with the ANC in the early 1950s, she was an apartheid activist who, due to her job as a machinist in a clothing factory between 1946 and 1952, had been involved in workers’ rights movements. Ngoyi was arrested for her participation in the Defiance Campaign of 1952 – for being in the whites-only section of a Johannesburg post office where she was caught composing a telegram to the then prime minister, DF Malan. She made history by being the first woman to join the ANC’s National Executive Committee, the party’s highest decision-making body. A year later, she was elected president of the ANC Women’s League. Mma Ngoyi, as she was known, became president of Fedsaw in 1956. The same year, she was arrested and appeared as one of the accused in the infamous Treason Trial. She was eventually acquitted, but until her death in 1980, her banning orders confined her to Soweto and she was repeatedly arrested and detained, mostly being held in solitary confinement.

Related podcast:

Ray Alexander was born in Latvia in 1914, came to South Africa in 1929 and, though still in her teens, began organising for Black workers’ unions. At the age of just 13, she had been active in the Latvian Communist Party and, soon after her arrival in her adopted country, joined what was then called the Communist Party of South Africa. She was the party’s secretary in 1934 and 1935, and actively recruited women to the organisation. Alexander was best known for her involvement with the Food and Canning Workers’ Union (FCWU) and, in 1953, while serving as its general secretary, received banning orders. Despite this, the following year she was a founder member of Fedsaw and was involved in drafting the Women’s Charter. However, additional banning orders in September 1954 forced her to resign from Fedsaw. “Her FCWU banning prevented her from attending the 1956 Women’s March to the Union Buildings, but she was involved in its organisation and recruited about 175 women from Cape Town.”

Helen Joseph was born in the United Kingdom in 1905, grew up in London and obtained a degree in English from the University of London. She taught for three years at a school in India before moving to Durban, South Africa, in about 1930. “In 1951 she took a job with the Garment Workers’ Union, led by Solly Sachs. During this time … Helen came to see and experience the ‘true face’ of apartheid, which angered her tremendously due to its blatant injustice. Not prepared to be a mere ‘voice’, Helen was a founding member of the Congress of Democrats [the ANC’s white ally].” In 1955, at the Congress of the People in Kliptown, Joseph was among those who read out parts of the Freedom Charter. She was arrested the following year and charged with high treason. Joseph was banned in 1957 and became the first person to be placed under house arrest; her final ban was lifted only in 1985.

Amina Cachalia was the youngest of the Fedsaw steering committee members and was born in 1930 in the former Transvaal. Her father was involved in the passive resistance campaign of the early 1900s that included renowned leaders such as Mohandas Gandhi. When Cachalia was 15 and studying at the Durban High School for girls, she was said to be determined to get involved in the women’s passive resistance campaign. However, because of her youth, the organisers were concerned about her safety. Through her interest in social justice, and her work with the Transvaal Indian Congress, Cachalia met Ngoyi and Joseph and played a role in the formation of Fedsaw, of which she later became treasurer. The oppression of women was a major concern for Cachalia and, some years before becoming involved in Fedsaw, she was instrumental in launching the Progressive Women’s Union, which sought to help women become financially independent.