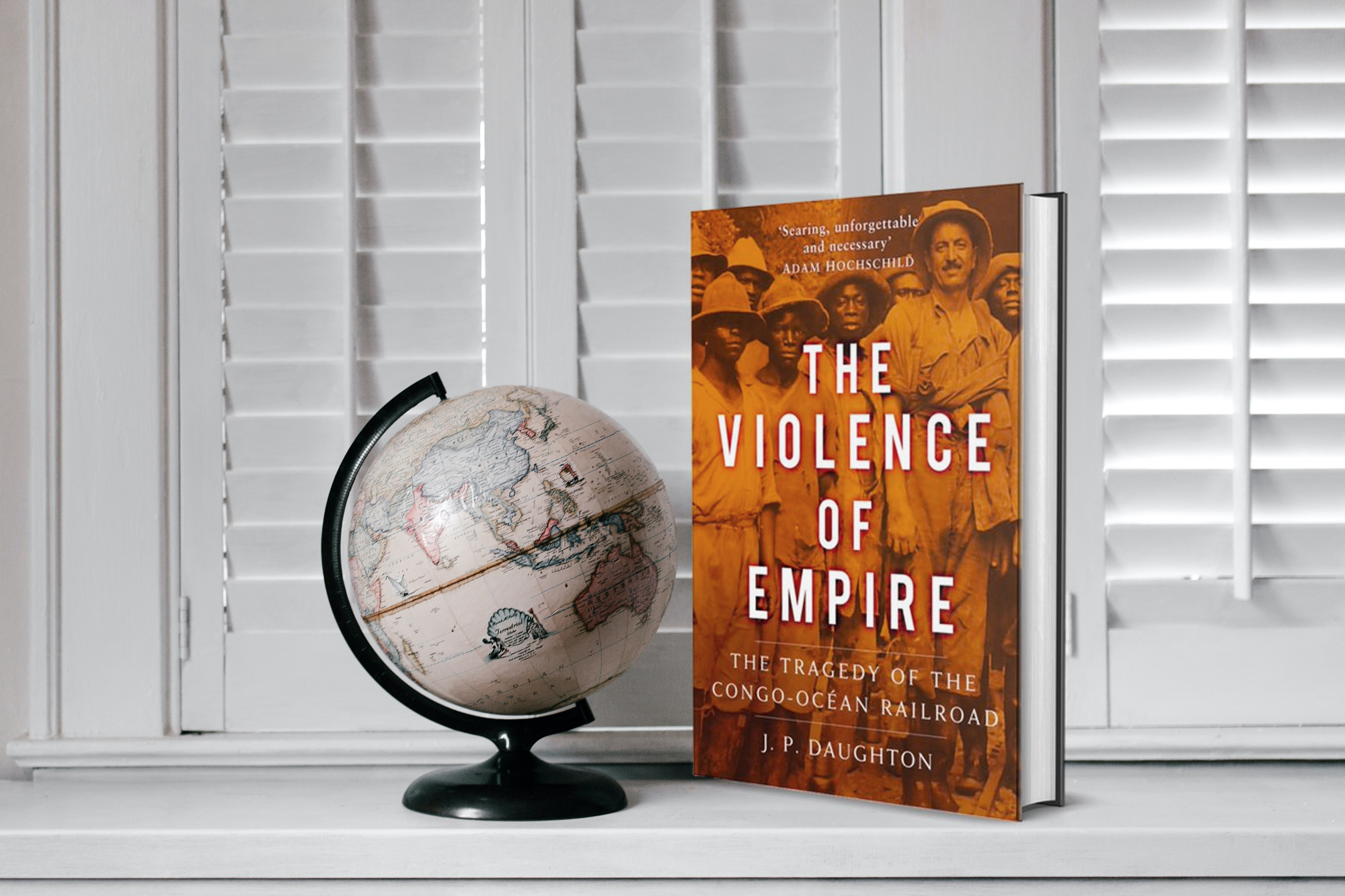

New Books | The Violence of Empire

The French colony’s Congo-Océan railroad, spanning just over 500km, was one of the deadliest construction projects in history, killing tens of thousands of men, women and children.

Author:

11 October 2021

This is a lightly edited excerpt from The Violence of Empire: The Tragedy of the Congo-Océan Railroad (The History Press, 2021) by JP Daughton.

Of thousands gone

“Utopians are heedless of methods.” J Rodolfo Wilcock

On New Year’s Day 1925, Marcel Rouberol, the chief representative of the Société de construction des Batignolles, one of the largest French engineering firms at the time, held a reception at his home near Pointe-Noire for the men who worked under him. It was one of many gatherings that company employees organised to fight the boredom, homesickness and sense of isolation that came with living and working on an inclement expanse of sand thousands of miles from home.

From 1921 to 1934, men from “the Batignolles” lived near the coast in Middle Congo, often referred to by the French as simply “the Congo”, a region in the southern part of French Equatorial Africa. They worked on building the Congo-Océan railroad, a massive construction project that the colonial government undertook in the years just after World War I. Long heralded by Frenchmen as essential to the economic development of the region, the railroad would connect the city of Brazzaville, the colony’s largest settlement on the upper Congo River, to Pointe-Noire, on the Atlantic coast, where the French planned to build a deepwater port. Covering only some 512km, fewer than 320 miles, the railroad was not terribly long. But it crossed difficult terrain, especially the dreaded Mayombe, where the rails wound atop unstable, sandy soil, through a region of thick forests, mountains and gorges.

A day like New Year’s was worthy of a photograph – 18 white men, all in pressed white linen suits, each with his white pith helmet in his hand. Corporations are built on hierarchies, so placement and positioning were essential in the picture, which was to be sent to company headquarters in Paris. The two men front and centre are Rouberol and M Martin, the lead engineer on the construction site. Around them are engineers, administrators and overseers of the project. Two African auxiliaries, perhaps assistants or secretaries, lacking white linen and helmets, are wedged against the right edge of the image, one of them literally cut off by the frame, behind their white superiors.

The Batignolles men exuded confidence on that New Year’s Day, none more so than Rouberol himself: his trimmed beard, neat tie and impeccably white shoes complemented the self-assured smile on his face. Receptions like this one allowed these men and a handful of wives to come together and celebrate their accomplishments and discuss the work ahead. Despite their distance from France, executives of the Batignolles recreated some of the comforts of home. Boats from Europe brought in not only supplies to build the railroad but regular shipments of garlic, onions and potatoes; refrigerated cheeses and charcuterie; jams and butter; rum, wine and Moët champagne; Vichy and Perrier mineral water; coffee, Cointreau and cigars. A New Year’s party was just the place to enjoy all that civilisation could offer.

Despite the inclement weather and prevalence of disease, the white men in the photograph, all well fed and standing tall, appeared to be paragons of camaraderie, cleanliness and health. The photo was a testament to France’s determination to triumph over the climate and landscape in a part of the world that Europeans considered insalubrious and uncivilised. The men of the Batignolles, as well as champions of the railroad in France, heralded the Congo-Océan as an engineering colossus achieved in the deadly wilds of the African continent. It would, as one newspaper put it, “save” Equatorial Africa, regularly called the “Cinderella” of the French Empire, and open the region’s “nearly limitless” reservoir of riches.

Related article:

While this portrait of colonial power is telling in many ways, there is another story that it does not tell – and that it in fact hides – in its straightforward simplicity. Just a short walk from the New Year’s celebration was the construction site of the Congo-Océan where African men and women worked 10 hours a day, six days a week, clearing millions of cubic metres of earth, building bridges and tunnels, and laying the ties and rails of the train line. For the 13 years of construction, the workers wore minimal clothes and lived communally in huts so crowded and poorly ventilated that many chose to sleep outdoors. They faced overseers, both European and African, who often verbally tormented and beat them. They survived on a starvation diet and often went days without eating. Fresh water was in short supply, adding to the problem of dysentery that continually weakened the labour force, at certain points sickening or killing more than half the workers. Needless to say, French cuisine was never on the menu.

A second photograph, also taken in 1925 and not far from Rouberol’s home, brings the plight of these workers somewhat into focus. This image illustrates a very different side of the railroad project. The emaciated frames of these two unnamed people, identified only as a “sick young woman and worker”, suggest they suffered from severe malnutrition and perhaps dysentery or beriberi, a thiamine deficiency common among the poorly fed recruits. The cachexia, or extreme wasting, of their bodies is reminiscent more of famine victims or prisoners of war than of what the French insisted they were – free, protected labourers in a republican empire.

Unlike the proud stances of the men of the Batignolles, these young people’s bodies and faces betrayed uncertainty, humiliation, fear and despair. It is impossible to know what exactly the “sick young woman and worker” thought about their predicament; the men of the Batignolles rarely documented the opinions of their workers in an effort to strip them of their voices and deny them their stories.

It is tempting to believe these two images came from different worlds, but they did not. Sent by steamer to France, the two pictures were placed in a book of photographs, not unlike an old family album, that the Batignolles kept in order to record the progress and history of the railway. The photograph of the two workers, with its unflinching documentary style, is reminiscent of many images used by humanitarian organisations to draw attention to atrocity and misery. The image, with the two young people framed by their background in a way that highlights their expressions and thin bodies, bears many hallmarks of what has been called the “aestheticisation of suffering”. But the purpose, or at least use, of this photograph was not to elicit sympathy or even pity. Instead, this collection of photos of workers, which were regularly left out of the company’s publicly published material, filled out a private collection aimed at commemorating every aspect of the construction, from frustrations to daily habits to triumphs.

Related article:

Flipping through the Batignolles album reveals black and white photos of open plains, dense forests, rivers and ravines; of labourers’ huts, tunnels, bridges, a wharf, hand-pushed mine cars filled with dirt and a newly built train station. There are photographs of the life of the construction for the Europeans, the white men and women carried by tipoye (sedan chair), or pushed in a wheeled pousse-pousse by African servants, or gathered for a concert in a high-ceilinged hall, or greeting the governor-general of the colony on a visit. It can make for jarring viewing. On one page, two white men and two white women out hunting strike poses worthy of a Tarzan film, their African guides standing to the side, visually fading into the background. And a few pages further on, a group of workers in the hot sun dig a massive trench without the help of machinery, pushing heavy wagonettes filled with dirt, under the watchful eye of European bosses. One, an image of leisure and adventure among the colonial elite; the other, a portrait of coerced labour. A caption of the first photograph identified the white men and women by name; in the second, the men remained nameless in a scene labeled plainly, “The Work at Kilometre 53”.

While such a juxtaposition seems striking now, at the time images of thin bodies, sick labourers and men working in the equatorial heat were accepted parts of the daily life of the Congo-Océan. Many Europeans on the construction site thought little of workers’ bodily conditions; indeed, most were convinced that Africans were better off for the work. In 1925 Gabrielle Vassal, the English wife of the French director of public health in the colony, wrote in her memoir that, while the workers’ rations were “frugal, consisting chiefly of manioc, it is at least regular, and in this starving country keeps them as a whole cheerful and healthy”. African malnutrition was a fact of life, she insisted, a by-product of inherent values. “The Congo population is always underfed,” Vassal continued with an insight shared by many fellow Europeans, “and it is impossible to sound the depths of their laziness and want of thrift. They never even think of the very next day.” The Congo-Océan – and all it represented about modern colonialism – would help rectify that.

Vassal’s opinions, like the Batignolles album, are remarkable less for what they say about colonial hierarchies and racism than for their consistent denial of the full story of the construction of the Congo-Océan railroad. Histories of colonialism, especially in Africa before World War II, are rife with examples of European assertions of superiority in the face of allegedly savage subjects. The triumph of “civilisation” over recalcitrant “primitives” – often bluntly portrayed in the European press as white men in pith helmets over naked, dark-skinned villagers – is a principal trope of modern imperialism. In this way, the Batignolles album was in keeping with European mentalities. What makes photos of champagne receptions juxtaposed with deprived workers particularly unsettling, however, is the casual coupling of the quotidian and the perverse. Recruitment to work on the Congo-Océan was widely recognised, by Europeans and Africans alike, as a possible death sentence. As André Gide, the future Nobel laureate in literature, put it after a visit to the French Congo in the mid-1920s, the Congo-Océan was “a frightful consumer of human lives”.

Related article:

Nearly entirely forgotten today outside central Africa, the Congo-Océan was one of the deadliest construction projects in history. The railroad likely caused between 15 000 and 23 000 African deaths, according to investigations conducted in the 1930s. Unofficial estimates were far higher, ranging from 30 000 to 60 000. In truth, the exact number of men, women and children who died in the building of the Congo-Océan can never be known. French government statistics were not kept until a few years into the construction, and even then they attempted to document only those workers who died on the worksite. The many thousands who died during recruitment itself, or who fled from the construction site never to be seen again, were not counted as casualties, even though many never made it home. Considering the serious administrative lapses evident during the construction from 1921 to 1934, even the statistics that do remain must be viewed with skepticism.

What is clear, however, is that the railroad was known, both in Equatorial Africa and in Europe, to be deadly. In France, its reputation gave rise to an oft-repeated assertion that the builders of the Congo-Océan laid as many corpses as railroad ties. In 1929 a biting cartoon from Le Journal du peuple showed a fat-cat capitalist, in white linen suit and with cigar in mouth, presenting the Congo-Océan, saying, “And that cost us only 2 000 ‘negroes’ per kilometre.” The steel rails stretch over the corpses of Africans.

Raw numbers of deaths fail to capture the full impact of the railroad on workers, their families and their communities. One of the most troubling dimensions of the Congo-Océan was how prolonged and quotidian the mistreatment and misery became. The difficult working and living conditions, combined with 13 years of sluggish progress, meant that the loss of life unfolded at a torturously slow pace. Hundreds died per month; thousands per year, year after year after year. Workers died at the hands of recruiters and overseers; they died in accidents and from wounds; they died of malnutrition, dysentery and very possibly, from a disease unknown to doctors at the time but now called Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or Aids.

In the history of construction projects, the mortality witnessed on the railroad in the French Congo has few peers. Even many premodern construction projects dependent upon enslaved labour rarely produced as many cadavers. In a little over a decade, more men and women died on the Congo-Océan than in 80 years building the Pyramids of Giza. In the modern era, railroad constructions around the world, including the building of thousands of miles of rails in the 19th-century American West, resulted in relatively few deaths compared to the Congo-Océan. Only the “French period” of building the Panama Canal in the 1880s witnessed comparable numbers of deaths – around 22 000 – where workers fell to a repertoire of endemic diseases including yellow fever, smallpox and typhoid fever.