New Books | Socialism is a human phenomenon

Focusing on the work of Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X, historian David Austin reflects on socialism and the role of black thinkers in shaping it.

Author:

21 February 2019

As the miners in Marikana, South Africa, know all too well, the fight for genuine and meaningful social change is hard graft. There is no easy road to freedom, and naked power in the black skin can be just as deadly and unfriendly as power in the white skin, irrespective of who possesses the ultimate reins of power.

Socialism is a simple word that has assumed multiple meanings in varied contexts over time. It comes with a great deal of baggage from the past, tied to failed states and disastrous attempts to exercise a new sense of freedom that was not defined by markets and capitalism. From Grenada to Belarus, socialist experiments failed to deliver the utopia that the idea has come to represent.

The reasons for this are varied, yet, if we define socialism as a social, political, and economic system that provides, but is not limited to meeting, the basic material needs of the population; as a set of ideas, beliefs, and values tied to the collective will of a society in which the majority of the population plays the defining role in determining its fate, while striking the delicate balance between collective rights and the freedom of individuals to develop and realise their creative potential as human beings; as a way to create in ways that nourish the human spirit while not being subsumed to the collective will; and, to be able to do so without fear of discrimination, recrimination or reprisal based on gender, sex, race, sexuality, or any other form of exclusion that denies human beings their humanity; to the extent that this is socialism, then socialism is a universal ideal that cannot simply be reduced to a set of ideas and practices that evolved within the context of Europe, or be limited to a Western conception of the world tied to pseudo-social and pseudo-scientific notions of progress and development.

Socialism is a human phenomenon and people of African descent have played an important role in critically engaging and redefining it: CLR James, Claudia Jones, Angela Davis, Aimé Césaire, Elma Francois, Frantz Fanon, Julius Nyerere, Amilcar Cabral, Walter Rodney, and perhaps most surprisingly, the founder and leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, Marcus Mosiah Garvey.

Garvey once declared that “the whole world will take on the social democratic system of government now existing in Russia. It is only a question of time”, and he praised the two most important leaders of the Russian Revolution while encouraging his followers “to do for Africa what Lenin and Trotsky had done for Russia in overcoming Czarist despotism”. He was particularly fond of Lenin, who had called for communist support for the struggles of African-Americans, and in his reflections on Lenin following his death in 1924, he declared that “Russia promised great hope not only to Negroes but to the weaker peoples of the world”.

I signal Garvey here because, as Robert Hill argued during his 1968 Congress of Black Writers presentation, it was Garvey, more than any other figure in the US, who paved the way for what would later be known as Black Power. Garvey is often derided and dismissed as a black nationalist and, by extension, anti-socialist figure, but his sympathy for the Russian Revolution, and the rationale behind it, suggests that his legacy is much more complicated and deserves more attention in this area.

WEB du Bois, Garvey’s occasional nemesis, was a communist for much of his adult life and was intrigued with the Russian Revolution from its inception. He travelled to the Soviet Union and other parts of Eastern Europe several times, beginning in 1926, and as King once remarked, “It’s time to cease muting the fact that Dr du Bois was a genius and chose to be a communist” because “irrational, obsessive anti-communism has led us into too many quagmires to be retained as if it were a mode of scientific thinking”.

This brings us to King himself, whom Coretta King described as the first black socialist she ever met. Martin Luther King realised that capitalism exacts a heavy toll on society: global warfare and the callous taking of life, environmental devastation, and the decimation of the human spirit. He had read The Communist Manifesto and Das Kapital, but as a minister of the church, he could not accept a dialectic – dialectical materialism – that ignored the spirit that was so fundamental to GWF Hegel, a fair analysis from a reverend.

But socialist as he may have been, for King, “communism forgets that life is individual” while capitalism “forgets that life is social. And the kingdom of brotherhood is found neither in the thesis of communism nor the antithesis of capitalism, but in a higher synthesis. It is found in questioning the whole society, it means ultimately coming to see that the problem of racism, the problem of economic exploitation, and the problems of war are all tied together. These are the triple evils that are interrelated.” For him, in the months and weeks before he was assassinated, race, class, and war were intricately connected, as opposed to fragmented parts of a whole.

King’s critique of both capitalism and communism leads us beyond a conception of society in which humans are treated as fragmented beings to be exploited and executed for the benefit of capital. This was Cornel West’s “radical King,” whose analysis of the Vietnam War led him to challenge the American military-industrial complex, which was willing to spend billions abroad on war while millions were mired in poverty at home, including African-Americans who fought for “freedom” in Vietnam while they lived a life of unfreedom in America.

But while King began to publicly denounce capitalism and the American war machine in Vietnam in 1967, Malcolm’s resolute critique of the war in Vietnam, which he also tied to the US war machine in Africa and the war against African-Americans at home, began in the early 1960s. For him, like King, there was no contradiction between his political-economic analysis and his faith or, put another way, in the spirit of liberation theology, their spiritual beings did not conflict with their appreciation of the dynamics of liberation from economic and racial exploitation.

Malcolm described the US as a “neo-imperialist power” in Africa and frequently referred to the nefarious role of “Uncle Sam” in Cuba, the Congo, Cambodia, Vietnam, and South America. He died an internationalist who, through his travels in Africa, Saudi Arabia, and Europe, shifted his analysis of race in the US, but by no means diminished its significance, situating it in relation to other forms of oppression across the globe.

Malcolm was particularly incensed with the murder of Patrice Lumumba and what he described as the “criminal” role of the US and the “American power structure” in the Congo in terms of supporting the recruitment and training of mercenaries who destabilised and eventually helped to overthrow Lumumba. He was shifting to an increasingly more radical, that is to say revolutionary, position, a direction that was more than evident in his 19 March 1964 interview published in the socialist journal Monthly Review.

The interview, conducted by the poet and jazz critic AB Spellman, is revealing in terms of Malcolm’s rapid radical and revolutionary internationalist shift in outlook only a few months after parting with the Nation of Islam, although the thrust of his views would suggest that he had already been thinking through these “new” convictions before his rupture with the Nation.

In the interview, Malcolm called for a black revolution, as opposed to a revolt, that would radically change the system in America. Despite his call for a sweeping, systematic, and structural change, Malcolm was clear that there could be no working-class, inter-racial solidarity as long as the white working-class racism persisted, and that black self-organisation and “black solidarity” was of paramount importance for the black revolutionary struggle.

In the last two years of his life, Malcolm also delivered a number of speeches on the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) platform and did interviews with socialists. This was the same organisation in which CLR James had played an active role in the 1930s and 1940s, and for which he had helped to formulate the autonomy, self-organisation and self-determination of the “Negro” that was outlined as early as 1939 during his historic meeting with Leon Trotsky in Coyocan, Mexico, and later published as Leon Trotsky On Black Nationalism and Self-Determination.”

Malcolm was increasingly shifting toward an analysis of class that complemented his analysis of racial oppression, a position that was enthusiastically supported by the SWP as well as Grace and James Boggs, both independent Marxists who had been James’ collaborators; and he was also looking not only to African countries, such as Ghana and Tanzania as examples, and the class and racial oppression of neo-colonialism in the Congo, but also paying close attention to developments in China, Vietnam, and Cuba as examples of socialism and anti-imperialism at work, framed by a Jamesian conception of self-organisation, or what has been described by Manning Marable in his biography of Malcolm as “James’s belief that the oppressed possessed the power to transform their own existence.”

It would not be a stretch to suggest that Malcolm had read James and Trotsky’s position on the self-determination as well as James’ The Black Jacobins. If so, it would also be safe to say that, along with his Garvey connections (recall that both his parents were staunch Garveyites and very active UNIA organisers), James, via Malcolm, would have played an important role in formulating the central position of Black Power that Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panther Party later developed.

He veered toward an internationalist position and began to consistently connect the plight of African-Americans with the dispossessed, damned, and condemned of the earth – in Vietnam, Congo, and Cuba, among other places – and consistently critiqued the US war machine, but he also described capitalism as a “vulture” that sucked “the blood of the helpless”.

Malcolm had become an internationalist who was now connecting the plight of US blacks with the conditions of the people of Africa, Asia and Latin America. This shift is further evident in Malcolm’s relationship with the Tanzanian revolutionary Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu, who would later be associated with Walter Rodney, and whom Malcolm invited to speak during an Organisation of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) event in New York in 1964. At the same event, a solidarity message from Che Guevara, whom Malcolm appears to have met in private in New York, was read to the audience.

Both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr had arrived at a point where they believed that freedom from racial oppression was incompatible with capitalism; that capitalism was antithetical to humanism in so far as it reduced the toilers of the world to fragments of themselves for the benefit of the few while eroding the spirit of all who were caught in its web.

We have no way of knowing what directions King and Malcolm would have taken in their respective lives if they had lived longer, but it is perhaps fair to speculate that their critiques of modern capitalism would have been more, and not less, resolute – perhaps adding an acute analysis of gender dynamics, sexuality, environmental devastation, and the prison-industrial complex.

As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor suggests, the Black Lives Matter movement – and here I include the BLM in Canada and the UK – has a great deal in common with the radical Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s in terms of its systemic analysis of racism in relation to capitalism, but one of the big differences being that in BLM, gender, sexuality, and ableism, among other forms of discrimination, have assumed a much more prominent role.

We will never know, but what is clear is that their critique of the coevals of race and economic class exploitation, alongside the military-industrial complex, was unequivocal and gestured toward a socialist vision – this is small “s” socialism, a vision of social justice in the broadest sense of the word; that is non-patriarchal, embraces members of LGBTQ community; and that is anti-racist, anti-colonial, and anti-imperialist; and in which the accumulation of capital and conspicuous consumption that has brought such dread to the planet is called into question and confronted.

While I am invoking a term that is laden with preconceived meaning, the strength of the socialist ideal, as I have defined it, and not as ideology, posits an egalitarian vision of the world with the potential to work across identity lines and toward a common egalitarian good.

Martin, and especially Malcolm, were shifting in a direction that was anti-capitalist and pro-socialist in their last years. In Malcolm’s case, his shift in the direction of socialism can be understood as an extension of his incessant critiques of the black bourgeoisie that had turned its back on the black majority, as well as his early embrace of the Cuban Revolution.

The fact that early FBI interest in Malcolm X within the Nation of Islam was primarily predicated on the impression that he might be a communist suggests that there is something threatening about the idea of challenging the international economic underpinnings of society. However, as James Boggs, the Detroit-based, African-American theorist, wrote in the aftermath of Malcolm’s murder, change requires movement, and movement requires building organisations, and organisations demand organisation – they have to be organised – but with a clear analysis, idea, and vision of what we are organising and fighting for, and how these aspirations might be realised – tactic and strategies. This cannot rely on spontaneous eruptions of protest and rebellion as catalysts for change.

As Boggs was also quick to point out, such a movement cannot rely and is not contingent on feigned manifestations of solidarity that patronise black folks as opposed to recognising that blacks have historically played, and continue to play, a crucial role in liberation aspirations and served as inspirations for global movements for social transformation. This is not black hubris, but an historical fact that takes on added meaning within the current global context, and especially, given the growing and alarming rates of black incarceration.

Boggs went on to state that “the Black Revolution is not anti-socialist or anti-communist, but is very much anti the Socialist and Communist Parties,” which have historically pushed for black solidarity with a white working class that was just as virulently racist as its bourgeoisie and hostile to the precepts of an egalitarian society. In other words, Boggs was calling for a socialism that would be divested of its old ideological baggage and biases, as well as of the practice of anti-black racism that impeded and continues to impede genuine solidarity, and he refused to subsume the needs of the black working class to this confused conception of socialism.

Socialism, as I have described it, is a set of ideas and values associated with a more just, egalitarian, and anti-oppressive society. It is the antithesis to the rabid capitalist exploitation, crude consumerism, cultural and economic imperialism, racial oppression, and environmental destruction that characterises our current moment.

In this context, the renewal or reinvention of the socialist or socialistic ideal, to use Malcolm’s word, and in the sense that I have described it, holds a key to unlocking the human potential and creativity that is necessary for building a new society, and people of African descent have an important role to play, as they have in the past, in defining how the movement toward such a society might unfold in the coming years.

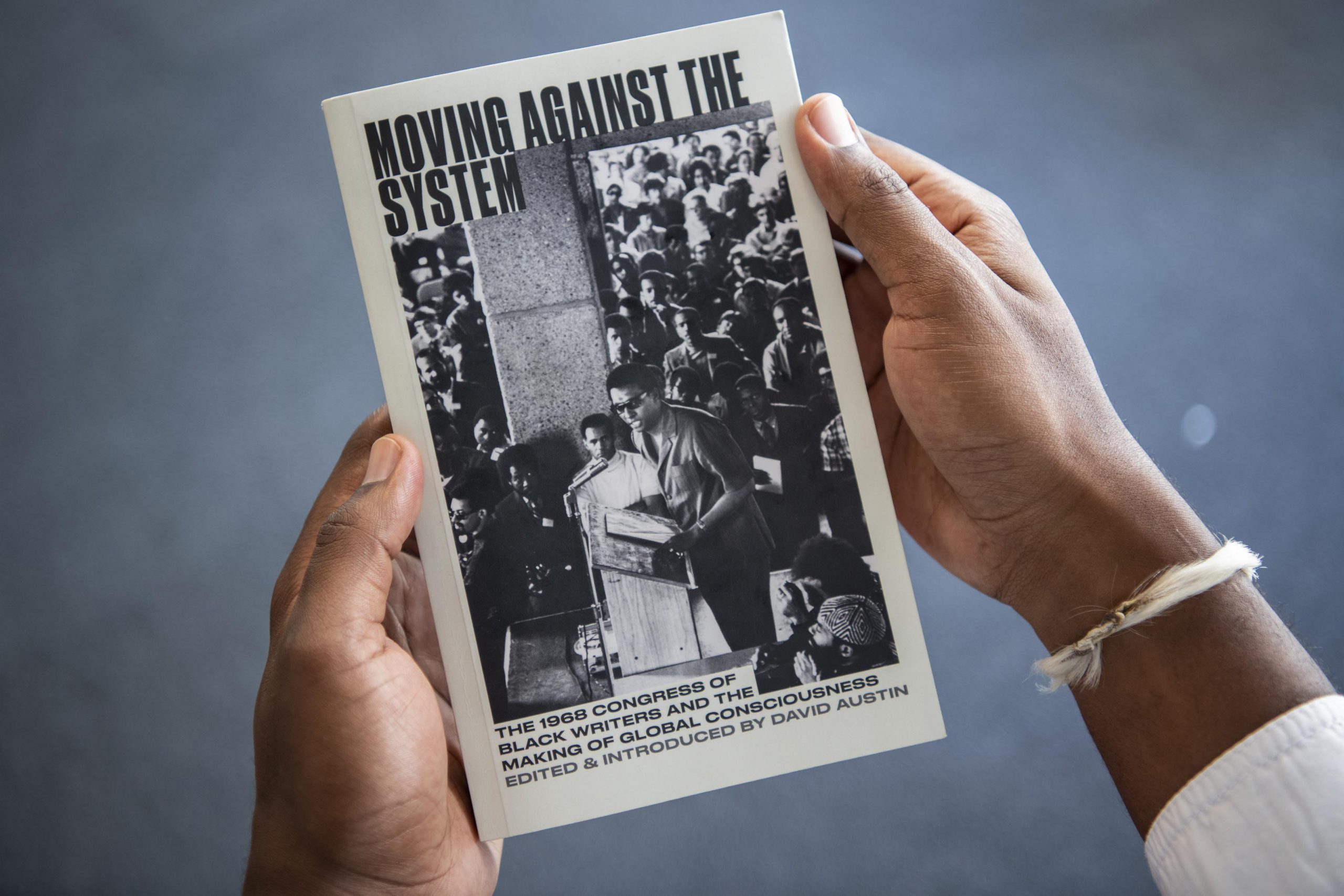

This is an edited excerpt from Moving Against the System: The 1968 Congress of Black Writers and the Making of Global Consciousness(2018), which is edited by David Austin and published by Pluto Press.