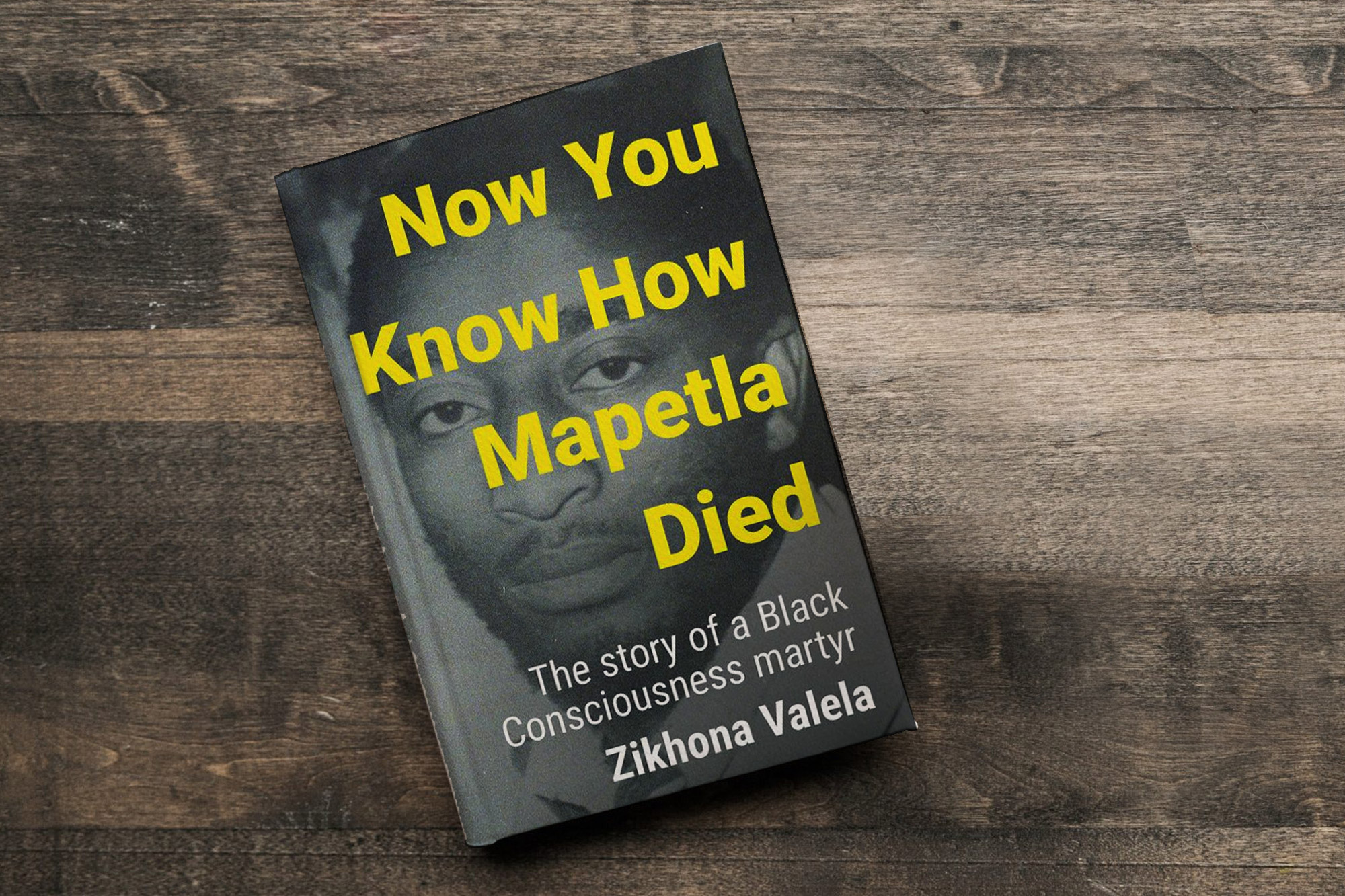

New Books | Now You Know How Mapetla Died

Mapetla Mohapi, a member of the Black Consciousness movement, died in detention in 1976. Historian Zikhona Valela teases out the threads that led to his death.

Author:

30 May 2022

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Now You Know How Mapetla Died: The Story of a Black Consciousness Martyr by Zikhona Valela (Tafelberg, 2022).

Bensonvale was as among the schools where students protested to the point of burning down infrastructure. When the ANC and the PAC were banned in 1960, the Cape Province saw a series of acts of sabotage in resistance to the increasingly repressive apartheid regime.

Bensonvale, which was both a high school and teacher training college, was founded in 1861 by the Methodist Church and named after the Reverend Joseph Benson. It was the first of its kind in Herschel district. The Reverend Benson was also Herschel district’s first missionary.

Bensonvale was initially meant for the enrolment of Black male students and was later opened to Black female students. The first Black secretary-general of the South African Communist Party, Albert Nzula, was a student at the school in 1919. Bensonvale became one of the hotbeds of resistance against what many activists referred to as “the system” – shorthand for apartheid.

Teachers were among the driving forces of resistance and conscientisation throughout the apartheid era. For instance, in the 1940s Winnie Madikizela-Mandela first encountered the ANC while studying at Shawbury High School in Qumbu; and in the 1970s Onkogopotse Tiro, assassinated in Botswana on 1 February 1974, is credited for politically influencing students at Morris Isaacson High School.

Related article:

As for Mapetla Mohapi, a teacher who influenced him was Mr Hintsana Nhonho. Mr Nhonho was a history teacher at Bensonvale (before becoming a school principal at Sterkspruit Senior Secondary) and member of the PAC in the Herschel district. Lovedale is where Mapetla’s future fellow comrade and close friend, Steve Biko, became politically aware of what was unfolding in the country. Biko had only just joined Lovedale in 1962 (coincidentally just as Thabo Mbeki was expelled) when he was first arrested with his older brother, Khaya. The police came to the school looking for Khaya who was suspected of being involved in Poqo, the armed wing of the PAC. Biko returned to school after his arrest, only to be expelled three months later. Although he was not involved in any political activity at the time, he was simply punished by association.

Poqo had a stronghold in the Cape Province in the 1960s. Although its armed struggle was unsuccessful in its aim of toppling the system, Tom Lodge argues “in terms of its geographical extensiveness, the numbers involved and its timespan, the Poqo conspiracies of 1962-1968 represent the largest and most sustained African insurrectionary movement since the inception of modern African political organisations in South Africa”. As the Cape Province accounts for much of this activity, Mapetla was sure enough exposed to the ideas of the PAC.

The family never discussed politics. It was simply too dangerous to do so. The stories of the Paarl Rebellion of 1962 and the 23 men arrested in Bhaziya on 5 February 1963 and sentenced to death had made headlines across the country. Though not all 23 were executed, five brothers were among the 12 executed by hanging on 3 July in 1964, while the Rivonia Trial was taking place. The youngest of them was only 18 years old, just a year older than Mapetla at the time. Men were arrested, tried and sentenced to death without thorough investigations. As the world rightly paid attention to the Rivonia Trial with bated breath about the fates of Nelson Mandela and his colleagues, families in the Cape Province reeled from what were essentially state-sanctioned lynchings.

Although Herschel was abuzz with underground activities, the political climate and the surveillance of activists, or anyone associated with them, were such that politics was spoken of in hushed tones. On the surface, Herschel in the 1960s seemed quiet, but this was only out of necessity as a result of the arrests of many leading figures of the banned organisations both in the district and the wider Cape Province. No one dared to speak openly about these things, not even in the comfort of their homes, for fear of the walls having ears.

Related podcast:

Recalling his conscientisation to fellow comrades, Mapetla talked often of the likes of AP Mda (who went underground in 1964), Joe Gwabeni, Selby Ngendane and Joe Nyathi Pokela, all of whom were from Herschel.

Gwabeni, Ngendane and Pokela were imprisoned on Robben Island for their work in recruiting for Poqo and for being at the coalface of armed struggle in the Eastern Cape and the Lesotho border area after the arrest of Potlako Leballo’s secretary, Cynthia Lichaba, and another woman courier, Thabisa Lethala, who were caught carrying pamphlets with instructions from the PAC leader to stage attacks on the system.

So influential and inspirational was the PAC on the lives of Bensonvale students that they staged a protest against the low quality of food at the school. Mapetla together with fellow students like Bhele Khongisa and Mongezi Ntoyi protested. The students faced expulsion and incarceration. The General Law Amendment Act, which empowered the police to detain activists for 90 days without trial, was already in effect. Mapetla was among the students at risk of detention or even worse. Nomafa Ntlemeza, a Bensonvale alumna, educator and former head of the Young Women’s Christian Association in Brandfort, and one of Madikizela-Mandela’s former neighbours, was a junior of Mapetla’s during this period. She recalls students who protested, leaving Herschel out of fear of punishment by the authorities. Families uprooted their lives and went into hiding because of how intensely any ANC- and PAC-related activity was cracked down upon.

Realising their son was at risk, the Mohapis moved from the Herschel district to King William’s Town and lived in the township of Zwelitsha. At this point Mphatsoe was an employee of the Ciskei, which, prior to its nominal independence, was an administrative region. This piece of information is crucial in enabling us to understand how Mapetla, who performed well in his studies, would end up enrolling so late for his degree.