New Books | Memoir of a South African film producer

Anant Singh has produced more than 100 films over four decades, including the Oscar-nominated Yesterday. He tells the story of his childhood and journey into filmmaking.

Author:

20 December 2021

This is a lightly edited excerpt from In Black and White: A Memoir (Picador Africa, 2021) by Anant Singh.

Even the circus was in on it

When Charlie Chaplin first swaggered into my life, it was on a big white sheet attached to the curtain rail in the lounge of our small but comfortable house in Springfield, Durban. This was the only place the sheet would fit so that was where it went. Affixed with pins at its four corners, it formed a screen of roughly 1.5 x 1.0 metres.

Much to the delight of his two sons, my father loved movies and he would hire a projector and bring home films for the family to watch. These were special occasions – Mummy happily ensconced on the brocade settee where she had kept a space for Daddy, for when he wasn’t checking the film reel, my grandmother, Parvati Singh, whom we called Ajee, in the small old wingback armchair that was reserved for her and her only. My brother Sanjeev would sit hugging his knees at Mummy’s feet, while my place was always cross-legged at the far end of the mottled rug so that I could satisfy my curiosity and keep an eye on Daddy as he readied the machine whirring at the back.

It wasn’t always Charlie Chaplin in his ill-fitting clothes tying us up in stitches. We fell in love with The Three Stooges and with Laurel and Hardy – the greatest comedy duo to have ever lived. Buster Keaton was another firm favourite – even without a single word of dialogue. The great stone face never ceased to keep us youngsters enthralled with his ability to maintain his decorum while around him everything went to hell. Sometimes my father kept us guessing. Who would it be tonight – The Tramp, Zorro or The Lone Ranger? Or maybe – yes, maybe – the wild antics of Moe, Larry and Curly?

Such enjoyment was infectious and Sanjeev and I thought of a way to share the entertainment with the neighbourhood children.

Related article:

“Sanjeev!” This was our father, calling from the top of a chair, which was balanced precariously against the back wall of our lounge, lined with furniture shifted to the side so as to leave empty floor space in the middle. “Anant! Bring the chair, please!”

We brothers stole a glance at each other, stifling giggles. Daddy liked to act all cross and grumpy but we knew that, secretly, he was happy to help us, to lend a hand, encourage our determination and dedication. Our parents had long resigned themselves to their sons’ initiatives, and the Singh boys’ “bioscope”, as our mother referred to it, had become something of a talking point among the children in Springfield. It was a source of excitement when word spread that the brothers had hauled out their mother’s sheet and were setting things in place.

The screen secured, Daddy would climb down off the chair, wipe his hands on the dishcloth my mother handed him and begin to set up the projector. Keeping one eye on the youngsters at the gate, he unpacked the 8mm reels from their cases and began to loop them in place. When he was done, he banged on the door. “Anant! Sanjeev! Come, bring your friends. We are ready …”

And with that pandemonium broke out. Little legs scurried through the gate, up the path and into the house as fast as they could, everyone scrambling for a place on the carpet, tiny ones in the front, the bigger ones at the back. Animated chatter, excited giggles, some prodding and teasing as everyone settled in.

It was my job to flip the switch and dim the light. I always relished that moment as I knew what was to follow. The joy we would soon see on those little faces as, wide-eyed, the neighbourhood children followed every move on the makeshift screen was magical. As soon as the projector ground to life and the whirr of the spooling reel was heard, a hush fell over the room. And then – dead silence, not a sound. Until Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy waddled onto the screen and our lounge erupted with raucous laughter. Sanjeev and I would turn to each other and smile. This was what it was all about.

Related article:

For the most part, Sanjeev and I were fortunate, in 1960s apartheid South Africa, in that we were relatively shielded from much of the horror, the harsh reality of the racism and violence experienced by so many elsewhere in the country. Safe in the embrace of our parents, our family, we saw little of what was unfolding beyond our home and the security it offered us.

I was born on 29 May 1956, the eldest son of Hareebrun and Bhindoo Singh. This was the year that African National Congress (ANC) leader Albert Luthuli was arrested and charged with treason alongside 155 others, including Nelson Mandela, Ahmed Kathrada, Walter Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, for daring to challenge the injustice that was apartheid.

I was four years old when the massacre at Sharpeville occurred on 21 March 1960. Police officers shot and killed more than 69 unarmed people, including children, protesting in a township on the goldfields up north in the Transvaal.

As small children, we did not yet know about the minefield of apartheid legislation or the Group Areas Act, which dictated where and how everyone would live, including us. It meant that we would grow up in an Indian neighbourhood and attend schools only for Indians. Springfield was one such Indian community and home, for us, was No 223 Quarry Road, a comfortable tin-roofed house with a single outdoor toilet. People very often lived with multiple family members, sometimes as many as 15 or so, in a single dwelling.

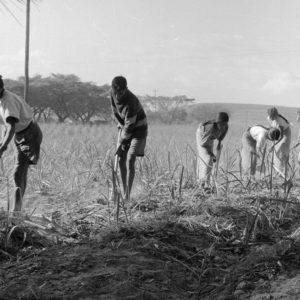

I had the good fortune of being born into a large family. My father was one of nine children – six brothers and three sisters – and he grew up in the same Indian community that had sprung up on the banks of the Umgeni River, the big, lazy, slow-moving mass of water that runs into the Indian Ocean at the Blue Lagoon about 7km further downstream. Sometimes, after heavy rain, the river would become a seething mass of angry floodwater, charging the riverbanks and wreaking havoc along its route. Our home was built only a short distance from the river, in an area known as Tika Singh’s Bend. Tika – short for Tikaram – was my great-grandfather, who arrived in South Africa as an indentured labourer to work the sugar cane fields of the colonial British.

Related article:

From what we have been able to determine from ships’ passenger lists and family records, the 22-year-old Tikaram and his wife Sulwantia, aged 25, disembarked in Durban on 3 June 1877. Tikaram was from the town of Mhow in the state of Madhya Pradesh in central India, and his wife was from Shahabad in the state of Uttar Pradesh. The couple would go on to have seven children: five sons and two daughters.

After completing his indenture, Tikaram opted to take up a plot of land rather than the free passage back to India and the family settled in Quarry Road. Here he became a successful market gardener, in time able to acquire additional plots further west on the banks of the Umgeni on a road that later became known as Siripat Road, and across the river in Sea Cow Lake, where some of his children would later settle on the land he gifted to them – including his daughters, a gesture quite unheard of in his day, when family wealth was deemed to be the right of sons only. Tikaram also leased a tract of land adjacent to the Quarry Road property from the Durban City Council. Here small plots were demarcated and rented out for informal housing, the rent revenue supplementing his income. This was the area that became known as Tika Singh’s Bend.

In time, Tika’s son Bunsee – my grandfather – continued to maintain the vegetable garden in the same field tended by his father, which became a welcome resource when it came to feeding and nurturing the growing brood that was the Singh family. As a youngster Bunsee spent many long hours working that plot of earth, his back bent, his neck burning in the blazing sun, his brow dripping from the toil. Here, on the banks of the Umgeni, he also tended the rose bushes that became one of his great passions, and which continued to bloom in profusion right into the 1990s after my father transplanted a few of them to our new home in the suburb of Reservoir Hills. Sadly, in the mid-1970s the portion of the land in Quarry Road that had the vegetable garden was forcefully expropriated; and at the same time the Siripat Road property was also expropriated to develop sports fields. The family received a paltry compensation of less than R1 for a square metre. The city official who was dispatched to negotiate with property owners was told by my very angry Uncle Jonsy that the price was insulting. One could not even buy fabric for that price, he said.

Balkumar, my father’s brother and the eldest of Bunsee’s children, took his older brother responsibility seriously: he kept a close eye on his siblings, especially when it came to the river. He and his younger brother Maania would scavenge for shrimps and freshwater crabs (the best, tastiest “seafood” ever) and other creepy-crawlies that made their home on the banks of the river, digging in and around the swampy shallows, while the other children played nearby. That was how we learned to experience the Umgeni – for leisure, irrigation, food, and the ebb and flow of our lives.

Related article:

Balkumar was well aware of the dangers posed by the river, the risk of young boys and girls being caught in the swells and eddies. He’d heard the stories, many of them, over and over. He did not want anyone in his family ending up like the neighbours’ little Leela, whose head had disappeared under the churning water and who hadn’t been seen again. At the same time his siblings knew that their big brother – Barka Bhai (meaning big brother in Hindi), as they called him – would never let that happen to them. Learning to swim was the first safety measure. Sink or swim. That was how all of us boys, growing up on the banks of the river, learned to swim. For the most part we taught ourselves and from an early age, five or six; girls at the time had fewer freedoms than their male siblings and cousins. In a city with sweltering temperatures, swimming was a way to cool off, but it was also a useful skill, a precaution against drowning. And there were many drownings over the years. Mostly it would be the elderly trying to cross the river to reach the market or young children who strayed too far and ended up in the water.

Balkumar – popularly known in later years as BB – had heard too many tragic tales to ignore the dangers. Becoming more and more concerned about the high rate of drownings, he took it upon himself to do something about it. Life was like that then; there was a sense of responsibility to the community. So it was that, in 1933, he garnered all his organising skills, rounded up some of his friends and founded a voluntary lifesaving club that would later become known as the Durban Indian Surf Lifesaving Club. For the Singh boys it was voluntary in name only, however; all the brothers were forced to join by my grandfather.

The lifesaving club, based in a hut structure at Durban’s Indian beach, was often called out to help search the river for a lost child or missing relative whom it was feared had succumbed to the raging torrent when trying to cross the river to get home. At other times, particularly during the hot summer months, they would simply keep a close eye on the river when families converged there to swim.

Related article:

Areas designated “White” at this time had all the amenities, while the demarcated Black, Coloured and Indian areas had none. Public swimming pools were reserved for the use of white people only and the beaches that were closest to us – the best beaches – were also reserved for whites. These spaces were off-limits to all people of colour, including us. I remember clearly our days at the beach – our “Non-White” beach was very different from where white people spent their summer days. The Nest, an eatery in a white beach area, had its own special facilities, toilets and even indoor seating. Of course all these luxuries were for whites only but – because “business is business” – we were permitted to place an order at the restaurant and be served on trays at our cars. These injustices linger in the hearts and minds of children all the way into adulthood.

Unsurprisingly, given the sociopolitical context of the time, the lifesaving club had no equipment or amenities, but Uncle BB was determined to change that. After serving in World War II in North Africa, he embarked on a fierce campaign for facilities for both the lifesaving club and a swimming pool in Durban where people of colour could be afforded the opportunity to learn how to swim. The struggle was long and hard. His battle against the Durban City Council and its politicians dragged on for nearly 20 years, hampered by the fact that we, part of the majority, had no fundamental rights, freedom or the vote.

Finally, on 2 June 1957 the first swimming pool for Indians only was officially opened in Durban – just one day short of the 80th anniversary of the arrival of Tikaram Singh in South Africa and three days after my first birthday. The pool, named the Balkumar Singh Swimming Baths in recognition of Uncle BB’s contribution to swimming and lifesaving, was in the neighbouring Indian community of Asherville. Uncle BB’s success here would spur him on to seek further and greater victories for his own community and the city at large. It would become a lifelong mission for him. By the time of his death in 1982 he had been instrumental in the opening of six swimming pools for people of colour in Durban.