New Books | Flow

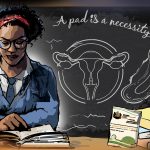

For menstruators without adequate sanitation, a normal bodily function jeopardises their access to work and school. The authors of Flow advocate for menstrual activism to change attitudes.

Author:

18 October 2021

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Flow: The Book About Menstruation (Kwela, 2021) by Karen Jeynes, Candice Chirwa, Pontsho Pilane, Tariq Hoosen, Claire Fourie, Ilana Johnson.

Menstrual rights are human rights

“You’re an adult now.”

For many of us, these are the words we heard when we had our first period. They marked an important rite of passage into maturity.

I recall that when I announced my first meeting with Aunt Flo to my mother, we had a serious discussion about the management of my period. It was a conversation full of fear and confusion, but we talked, nonetheless. That openness is something that many young people who menstruate do not have in this country.

Why not? Well, it’s because it is still unacceptable to talk openly about menstruation, to make it visible. When we think of how society portrays menstruation, it is usually in the format of horrific PMS jokes or first menstruation horror stories, and this results in socialising our young menstruators to expect to hate their periods, even before they have them.

We should acknowledge that menstruation affects everyone differently, but the purpose of this chapter is to illustrate how the lack of resources can have a socioeconomic impact on menstruators and therefore be a violation of human rights. Ultimately, the obstacles and challenges menstruators face due to their periods puts young girls, in particular, at a major disadvantage compared to their male counterparts and this contributes to inequality.

Related article:

Now if you’re like me who is a passionate feminist, you will likely believe that having a natural bodily function shouldn’t be an obstacle in our lives.

You’ve probably read the title of this chapter and thought: how does menstruation have anything to do with human rights? The significance of how we view our periods is important in the discussion of the dignity menstruators are entitled to when it comes to placing menstrual health within the human rights agenda.

When you think of the access to products, sanitation and information needed in managing your period, ask yourself whether you’d be able to manage it without those basic necessities. And then think about the young girls, women and menstruators who don’t have access to sanitary products, clean water, safe facilities, sexuality education every single month.

Gender inequality, extreme poverty and harmful traditions can all make menstruation fraught with deprivation and stigma. All around the world girls, women, transgender and intersex people suffer from the stigma of menstruation through cultural taboos, discrimination and the inability to afford sanitary products. This is also known as period poverty. When “that time of the month” arrives, so does a range of economic and social burdens on young girls during their time of transition into adulthood.

Menstruation is linked to human rights because when menstruators cannot access safe facilities and safe and effective means of managing their periods, then they are not able to manage their periods with dignity. Menstruation is fundamental as it unites the personal and the political, the intimate and the public, and the physiological and the socio-cultural. If not properly managed, it can either facilitate or impede the realisation of a whole range of human rights. And I am pretty sure that most people did not know that.

Related article:

Furthermore, the universal declaration of human rights states in its preamble that all human beings should be recognised for their inherent dignity. The stigma and shame generated by the various stereotypes around menstruation have severe impacts on all aspects of women’s, girls’ and menstruators’ human rights, including their right to equality, health, housing, water, sanitation, education, freedom of religion or belief, safe and healthy working conditions and to take part in cultural life and public life without discrimination.

And again, when we think of periods, we are beset with TV commercials that depict the happy-go-lucky girl who is always ready for the day and menstruates magical blue liquid. This misrepresentation of our lived experiences while menstruating is harmful and can lead to potential human rights violations all because we are not having enough conversations about the various obstacles that menstruators have to go through month to month. These inaccurate depictions of our lived experiences have often led to non-menstruators – mostly cis gendered men – assuming that when we menstruate, we are overreacting, and that our cramps are something we can get over. When this is simply not the case.

Again, we as menstruators are meant to be afforded the right to comprehensive sexuality education that allows all of us to be empowered about our bodies and to make the necessary critical decisions that have an impact on our sexual and reproductive health. However, that is not the reality of many menstruators throughout the world. In certain societies, menstruators are punished through banishment and isolation. In countries such as Tanzania, Mali, Nepal and India, menstruators are forced to remain isolated in “menstrual huts” during their periods. In 2016, in Nepal, a 15-year-old girl (Roshani Tiruwa) died due to smoke inhalation as she was expected to remain in the menstrual hut. As well as being forced to sleep in huts, girls, women and menstruators having their period usually have extreme outdoor labour during the day. They are restricted in who they can work with and are only given limited food. In certain extreme cases, many girls and women are banned from reading and writing while menstruating. Cultural practices like in Nepal encourage the discreet management of blood flow and discomfort resulting in people keeping their experiences of menstruation hidden and secret.

Menstruation is conveyed as a matter that is not worthy of public debate due to societal perceptions that associate menstruation with “privacy” and “shame”.

Related article:

Understand that the silence we continue to perpetuate has an impact on menstruators who go to school and work. Menstruation causes a lot of problems for those who are still at school. Let’s take South Africa for example, a country that has high insufficient sanitation in schools and rural communities, and let’s then try to figure out how a young person at school is expected to change their sanitary resources in a pit latrine without adequate water. Possibly, this results in blood-stained clothes, which in turn can lead to stress and embarrassment. Their human rights have been violated. Let’s think for a moment about the long distances that people who menstruate have to walk to school. The fear of bullying by boys. The lack of effective menstrual materials, and of sex education, and of adequate facilities. What impact do all these things have on education?

When it comes to menstrual health in relation to work, we need to consider that there are two aspects to the human right to work: the right to choose or accept employment freely, and the right to fair and favourable working conditions, which include the right to safe and healthy surroundings. Employees in the informal sector have the same rights. However, in this case, it is the latter aspect of the right to work that is the most important. The right to safe and healthy working conditions means adequate water and sanitary facilities in the workplace. Now consider the informal employee who has a heavy period and is forced to wear rags because their workplace does not provide sanitary products. This is the reality for factory workers in Bangladesh. It even gets worse: factory workers who menstruate are sometimes obliged to take contraceptive pills to reduce their flow, and therefore lessen their toilet use during menstruation as the toilet infrastructure is not suited for their basic menstrual health needs.

We cannot downplay the role of menstrual activism, which is a product of third-wave feminism. I can acknowledge that attitudes are slowly changing thanks to the work of activists and international organisations. These organisations and activists are crucial where they have the power to make a cultural change within the domestic level where states cannot. There are hundreds of websites and Facebook groups, like Menstrual Matters and Period Positive, dedicated to education around periods. The use of mass media and other media channels for communication can affect social norms by reducing taboos around menstruation.

Related article:

Yet there is more to be done – especially on the state level. Our governments can and should play an important role in the de-stigmatisation of menstruation. Perception of menstruation is affected by government policies in education, development, business, taxes and healthcare. The role of the state is to develop, apply and monitor adequate labour standards, including standards that require employers to provide safe, healthy working environments that meet the needs of menstruators during their menstruation.

Menstrual rights are human rights. Menstruation is important in all aspects of life because menstruators need to be able to manage their menstruation wherever they find themselves. The menstrual cycle revolves around equality. Menstruators pass up education, training, work and different socioeconomic opportunities in life when they cannot deal with their menstrual cycle with humanity and pride. Menstruation is a human rights matter. Numerous human rights are essential to guarantee that menstruators can deal with their period effectively. This incorporates the right to water, sanitation, health and education, including sexual and reproductive health education. Menstruation is a human rights matter because misguided judgements and negative social standards surrounding menstruation are harmful to menstruators and in certain cases can lead to death. There is great power in speaking openly about menstruation as it could contribute to the removal of societal and cultural conceptions that menstruation is a shameful and private event that must be kept secret.

Openly talking about periods could ultimately save lives. It is time to realise that menstruation is not shameful. Period.

Brief timeline on menstrual activism

In European and North American societies through most of the 1800s, homemade menstrual cloths made out of flannel or woven fabric were the norm, which is where the saying “on the rag” comes from.

1930s-1940s: Modern disposable tampons were patented in 1933 under the name “Tampax” and commercial menstruation products were first sold. Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner, an African-American inventor, patented an adjustable sanitary belt that held a pad in place, the first product of its kind.

1950s-1990s: Different versions of maxi pads for different flows, and pads with wings were introduced to the market. In apartheid South Africa, menstrual products in prisons were weaponised.

Related article:

Between 1979 and 1996: Over 5 000 cases of Toxic Shock Syndrome were reported, and the reason was probably the lack of regulation over materials and the questionable safety of the composition of menstrual products. This caused health scares and prompted menstruators, who resented the fact that they were expected to hide and feel ashamed of their periods, to bleed freely without the use of any menstrual products.

2000s to present: Products and ad campaigns starting to shift focus more on all bodies that get periods including trans men and gender non-binary people. They also mostly started using red to demonstrate product absorption, rather than blue.

Mid-2015: Movement became mainstream on social media, putting pressure on governments around the world. Countries like Canada stopped taxing menstrual products.

In 2018: South African Minister of Finance, Tito Mboweni, announced the removal of VAT on menstrual products as they are non-luxury items.