New Books | Black education during Jim Crow

Civil rights leader and renowned journalist Percival Leroy Prattis was just one of many tireless activists who excelled in their studies before going on to fight for racial justice.

Author:

17 May 2021

This is a lightly edited excerpt from Haste to Rise: A Remarkable Experience of Black Education during Jim Crow (PM Press, 2020) by David Pilgrim and Franklin Hughes.

This article contains racist language that depicts life under Jim Crow conditions in the United States.

Race news: African American journalists

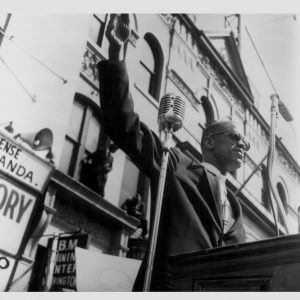

Percival Leroy Prattis was a pioneering journalist, influential newspaper executive and nationally recognised civil rights leader. He was the city editor of the Chicago Defender when it was the nation’s leading African American weekly newspaper. Later, he spent 30 years at the Pittsburgh Courier, another prominent Black paper. In 1947, as a representative of Our World magazine, he became the first African American news correspondent to be admitted to the United States House and Senate press galleries. Prattis rivals Belford Lawson as the most accomplished of the Hampton students who came to Ferris.

He was born on 27 April 1895, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Alexander and Ella (Spraggins) Prattis. He began his education at the Christiansburg Industrial Institute in Cambria (now Christiansburg), Virginia. The school was founded by Charles S Schaeffer, a Union soldier and Baptist minister. Working for the Freedmen’s Bureau, Schaeffer came to Christiansburg in 1866 and taught former slaves in a rented house.

In 1870, the Friends Freedmen’s Association, a Quaker group, became the main financial backers of the school. In the 1880s, Schaeffer turned over control of the school to a completely African American staff. Booker T Washington became an adviser to the Christiansburg Institute in 1896. Soon after that, the school changed its curriculum to align it with those at Tuskegee and Hampton. Prattis remained at Christiansburg for four years, literally working his way through school – milking cows at the school’s dairy farm during the day and attending classes at night. He was valedictorian of his class.

Related article:

Prattis left Christiansburg on the night of the day that he was graduated, taking an all-night train across the state. He was 17 years old and on his way to Hampton Institute. He would later write: “As I catnapped through the night, I felt like I was riding in the sky – I was going to the great Booker T Washington school, the school which motivated him to found Tuskegee Institute.” Christiansburg and Hampton were both Black schools with a focus on practical education, but the young Prattis quickly noticed differences:

“At Hampton, the picture was different from Christiansburg. Hampton was much larger, with many more impressive buildings. It was like a small town. There were more students than at Christiansburg. The students were Black and red, or Negroes and Indians. As nearly as I can recall, not more than three of the academic teachers were Negroes. Some of the teachers of trades were white. The head of the Agricultural department was a white graduate of Pennsylvania State College. All of the white teachers, male and female seemed to have been graduates from northern colleges and universities. They were affable, friendly and devoted to their responsibilities as servants for the students.”

Without much money, Prattis had to work his way through Hampton – he worked in the institute’s dairy farm for three years. Because of this work, he was placed in the agricultural programme (which took three years to complete). He wanted to enroll in college preparatory courses, but the school did not offer many, and the ones that were offered conflicted with the requirements of his programme. Prattis spent many hours searching for his life’s path. His experiences at Christiansburg and Hampton were more training than education – training to accept life as a farmer, albeit one able to teach others to farm. He wanted something different.

“I had to admit that I did not want to spend my life behind a plow or milking a cow. I had no prejudice against farming. Farming was the basis of civilisation in Egypt and Samaria thousands of years ago. Even so, I never had the feeling that I could make good, be successful as a farmer.”

Related article:

Some of his classmates told him about a school in Michigan, where a Black man could take college preparatory courses. He did not have the money for tuition. So, in 1915, the year after graduating from Hampton, Prattis took a job as “poultry master” – actually a foreman – at Shellbanks farm, an auxiliary of Hampton. In the fall of 1916, he enrolled at Ferris Institute to “pick up the academic subjects that Hampton’s vocational programme had not provided”.

Although battered by a difficult Michigan winter – “temperatures hovering around 40 degrees below zero” – Prattis found his year at Ferris to be rewarding.

“Ferris Institute was really great. It was an acknowledged ‘cram’ school. Everybody worked hard, including the teachers. If you needed extra tutoring, the teachers gave it to you without extra cost. Our saint, of course, was Woodbridge N Ferris, the white-haired founder of the school who later became Governor of Michigan.”

Today, the word cram has a slightly negative connotation, meaning, to prepare hastily for an examination. When Prattis referred to Ferris as a cram school, he meant that the college preparatory programme offered short intensive courses. And Prattis wanted to delve into as much learning as he could squeeze into an academic year.

“I was at Ferris from September 1916, until June 1917. During that period, practically 10 months, I covered the following courses: two of French, two years of Latin, algebra, plane geometry, trigonometry, rhetoric, physiography and spelling. According to present day grading, I made A’s [above 90] in all subjects but trigonometry in which I made 85 … It would be a grave sort of indifference for me to fail to name some of the teachers who went out of their way to help me. Among them were Mr Masselink, vice president, who taught in the college preparatory department; Mr Carlisle regarded as the ‘biggest little man in the state’; and Mr St Peter who, it was reputed, could do anything with electricity: and carried tables for mathematics in his head. These men made me feel like I had a chance in life. So did many of the students.”

Related article:

This is a poignant and revealing testimony. At a time when the South – and other parts of the country – still had racial hierarchies, Prattis felt welcomed at Ferris. He was involved with the Wednesday night debate club and the interscholastic debate team. He was also selected as one of the editors for the yearbook. He graduated from the college preparatory programme in 1917. He planned to enter law school, but those plans were interrupted when he was “called up to the army”.

“I was inducted in August 1918, and sent to Camp Sherman, Chillicothe, Ohio. The going was not rough once we reached camp. Our training was a bit peculiar. My first training was in the peeling of potatoes. I was given a stool to sit on outside the camp kitchen and put on KP [kitchen police] duty. I did nothing but peel potatoes all morning. However, after lunch I would stroll up to the company office to see if anybody was using the typewriter.”

One can dispute the reasons that the United States joined World War I, but there is no arguing that a popular narrative was that the United States was fighting for its liberty and attempting to spread democracy. Although many Black Americans rightly saw the hypocrisy in this narrative, they hoped that if they fought – and fought bravely – when they returned to this country they would be granted the basic rights denied to them. Hollis Burke Frissell, the principal of Hampton Institute, sent letters to Hampton graduates calling on them to “stand shoulder to shoulder” with all Americans to “rally to the defence of the nation”.

Whether influenced by Frissell’s letters or not – Hampton graduates joined thousands of other Black men in “the war to end all wars”. They saw military service, a significant civic obligation, as the way for them to be treated as first-class citizens.

Unfortunately, Black soldiers could not escape Jim Crow. Black people were not allowed to serve in the marines and the navy confined them to mess duty on ships. Most Black soldiers in the army received inadequate training and served in labour battalions. Prattis summed it up this way:

“There were many of these [Black] regiments. Ours was known as the 813th Pioneer Infantry Regiment. How easy it is to delude with words! We were not really going to France to fight, although some of us might carry. We were being shipped over there to work, to do the hard and dirty work. All except me.”

Related mixtape:

His unit was made up of Black enlisted personnel and junior officers, supervised by white senior officers. The unit was responsible for filling shell holes, helping with road construction (often under fire), clearing battlegrounds and reburying bodies that had been hurriedly buried at the time of their death.

“We were all members of the 813th Pioneer Infantry. Uncle had not planned for us to do anything new or different in France. We had worked with our hands in the good old USA and Uncle planned to put our hands to work in France. Pioneer Infantry meant ‘pioneer work’ or ‘pioneer labour’. For everybody but me.”

A white colonel from Alabama pulled Prattis away from the other Black soldiers. He had seen him using a typewriter. He asked Prattis about his schooling. Prattis told him about his experiences at Christiansburg, Hampton and Ferris. He talked about the courses that he had taken. When the questioning concluded, Prattis was promoted to a sergeant major and told he would work behind a typewriter – over Black privates, corporals, sergeants and first sergeants. Prattis was pleased. “Man, that was something – a private one day and a sergeant major the next. My weapon from that point on was a typewriter – and I had rank.” He never carried a pistol or rifle.

He was stationed in France from 15 September 1918 to 13 July 1919, and was honorably discharged from his duties on 23 July 1919. His military service gave him the beginnings of a global perspective, which served him well in future reporting from and about Europe, Africa and Asia. It also inflamed in him an even greater dislike of Jim Crow racism.

After returning from the war, Prattis settled in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He knew the city well. It was only 50 miles from Big Rapids, and he had spent several months there before reporting for military duty. He had worked first in a barbershop – “to keep a barber shop clean and to shine the shoes of customers” – then later as a bellboy in the Pantlind Hotel. Although he had been a sergeant major, after returning to the country, he still only found menial labour: this time work as a waiter at the Pantlind Hotel.

Related article:

While working at the hotel, Prattis was asked to substitute for Roscoe Conkling Simmons, a celebrated orator who had been scheduled to speak at a fundraising dinner for the Red Cross. This brought Prattis – and his talents – to the attention of the Black community in Grand Rapids. Around that time, he also joined with his friend George Smith to begin a weekly newspaper targeted to the local Black population. Smith, a printer and the secretary of the local National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), had access to printing equipment but needed someone to function as editor and reporter. He asked Prattis to join him. Prattis was flattered but uncertain.

“I agreed with hesitation. I knew nothing about journalism. My real love was mathematics and I could work all night on a single math problem. In mathematics, you know there is a ‘right’ answer but in writing – poetry, novels, news stories – it is hard to say for sure when, if ever, you have arrived at the correct answer.”

Thus began Prattis’s career as a journalist and executive. The Michigan State News became the first African American newspaper in Grand Rapids. The paper’s motto was “Michigan’s Race Paper”, and it was unapologetically an opponent of Jim Crow laws and practices. Smith was an NAACP officer; therefore, the Michigan State News highlighted the work of that organisation. For example, an early edition of the newspaper gave extensive coverage to the visit of Walter White, national secretary of the NAACP, to Kalamazoo and Lansing. Randall Jelks, a historian, summarised the relationship between the newspaper and the local African American community:

“The Michigan State News bolstered the work of the NAACP and kept the small African American community in Grand Rapids informed about civil rights matters nationwide. The paper and the work of the national NAACP provided the encouragement that some in the African American community needed in their own battle with Jim Crow.”

Related article:

Prattis worked for the Michigan State News when he was not required to be at the hotel, and he must have enjoyed it, because he worked without pay. His time at the newspaper awoke in him a love of journalism and a belief that papers run by Black people could be tools of activism. He had not been naive about race relations – some of his schooling was in the South, and he served in a segregated army – but his time spent at the Michigan State News gave him a deeper understanding of racism and a vehicle for addressing racial injustice.

He worked at the Michigan State News for two years and likely would have stayed longer, but an incident at his paying job provided him the impetus to leave Grand Rapids. White waitresses at the Pantlind Hotel called one of the Black waiters a nigger. The Black waiters caucused and decided to make a demand of the hotel managers: the white women should be fired. If the women were not fired all the men – 30 Black men – agreed that they would quit en masse. This did not turn out well for Prattis.

“I was too wet behind the ears to realise that men with families who were probably paying for their homes and furniture, would take some second thoughts before giving up their jobs and jeopardising the welfare of their families. The manager would not fire the girls. When the time came to quit, as we had threatened, only three out of 30 quit. I was among the three. That was why, in January of 1921, I found myself in Chicago completely alone.”

He arrived in Chicago without money. Once again, he found employment as a waiter. Shortly thereafter, he was introduced to Robert Sengstacke Abbott, founder and publisher of the Chicago Defender. Abbott was drawn to Prattis. Both men had attended Hampton Institute – and both believed that a Black-run newspaper could be a powerful tool in the fight against racial injustice. A month after taking a staff job on the Defender, Prattis was promoted to city editor, a position he held for two years. Prattis wrote articles and features under his name and under the pen name Roger Didier.

Related article:

If Prattis’s activism was awakened at the Michigan State News, it was fed at the Chicago Defender, one of the loudest voices encouraging Black people to leave the Jim Crow South. The Defender published editorials, cartoons, and articles – even job listings and train schedules – to persuade African Americans to move to northern cities. Under the leadership of Abbott, the Defender reported the news that mattered to African Americans – for example, coverage of the riots of 1919 – and campaigned for anti-lynching legislation, fair housing policies and the integration of major professional sports leagues. The newspaper was an uncompromising foe of Jim Crow. It seemed like Prattis had found his professional home, but an “unfortunate disagreement”, as he put it, with Abbott led Prattis to resign from the newspaper.

Prattis was not out of work very long; in May 1923, he landed a position with the Associated Negro Press (ANP), founded and led by Claude A Barnett, a graduate of Tuskegee Institute and an admirer of Booker T Washington. In 1913, Barnett sold advertisements and photographs to Black newspapers. He soon realised that these newspapers lacked reporters. In 1919, he created the Chicago-based ANP, which provided Black newspapers with stories, commentaries and featured essays that focused on the Black experience, including Black people in African countries. Prattis and Barnett also created the National News Gravure, a photogravure supplement that the ANP designed for distribution by Black newspapers.

Although primarily a news-sharing operation, Barnett wanted the ANP to also be a source for news coverage. Prattis served as the ANP’s city editor, and he worked as a reporter. He travelled on assignment and reported on domestic and international stories. In 1930, Prattis accompanied the Special Committee for the Study of Education in Haiti, headed by Robert R Moton, president of Tuskegee Institute. The State Department recognised him as an accredited journalist and paid his travel expenses, as if he were a member of the commission. While in Haiti, he addressed several groups of local journalists.

His experience in Haiti led him to call for more friendly relations between Black Americans and Haitians. When Prattis left in 1935, the ANP served over 200 newspapers and magazines across the United States. After a 10-week stint as city editor of the Amsterdam News in Harlem, in 1936, he joined the Pittsburgh Courier, which had eclipsed the Chicago Defender as the most influential Black newspaper in the country, with a circulation of over 250 000. He served as city editor until 1940, executive editor until 1956, editor-in-chief until 1961, and finally as associate publisher and treasurer until 1963.