‘Nevermind’ at 30: an enduring legacy of rebellion

The album that catapulted Nirvana to stardom still stands as a symbol of resistance to consumer capitalism, drudgery and alienation, even as it has been co-opted by these very forces.

Author:

29 September 2021

American rock band Nirvana, with a crowd of riotous extras, gathered on 17 August 1991 at a soundstage in Los Angeles to film a music video for their upcoming single, Smells Like Teen Spirit. The group hired video director Samuel Bayer because they liked the lo-fi quality of his earlier work, finding it “not corporate” and “punk”.

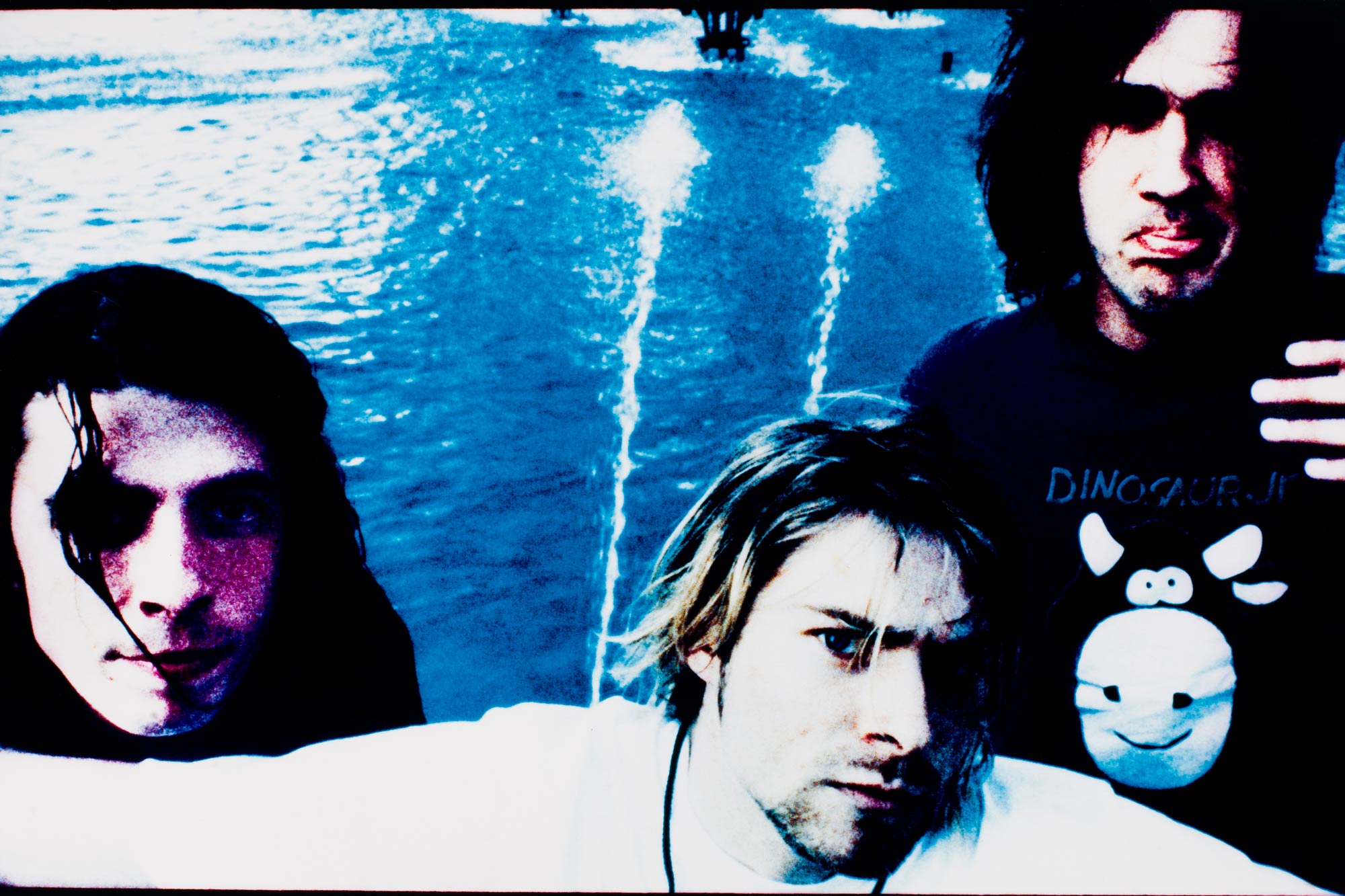

The video featured scenes of chaos inside a high school auditorium, complete with cheerleaders clad in anarchist symbols. Teen Spirit’s grimy aesthetic reflected the underground American punk scene in which singer and guitarist Kurt Cobain, bassist Krist Novoselic and drummer Dave Grohl had been active participants in the 1980s.

As historian Kevin Mattson writes in his 2020 book, We’re Not Here to Entertain, this was a counterculture that, in spite of its delinquent image, was focused on DIY creation and self-expression. From bands like Black Flag and the Dead Kennedys to filmmakers, poets and comic book artists such as The Simpsons creator Matt Groening, United States punk was a bastion of leftist values during the highly conservative years of Ronald Reagan.

From 1981 to 1989, Reagan implemented hyper-capitalist economic policies, drastically reducing the political power of the American working class. He supported criminal regimes like apartheid South Africa and joked about starting a nuclear war.

Punk had arrived in the US in the late 1970s, after British bands like the Sex Pistols had scandalised the United Kingdom with their outrageous interviews and anti-establishment lyrics. But, while it failed to achieve mainstream commercial success, it slowly seeded itself city by city, state by state.

This process was mirrored across the world. From Eastern Europe to Asia, punk became a beacon for those who felt outcast from the dominant class and gender structures. As Jon Savage wrote in his acclaimed book England’s Dreaming, released in 1991, “punk was an international outsider aesthetic: dark, tribal, alienated, alien, full of black humour”.

Punk mocked power, while offering its own form of autonomy and participation. It had, in Savage’s words, “an infernal power that offered the chance of action, even surrender – to something larger than you – and thus possible transcendence. In becoming a nightmare, you could find your dreams.”

In a highly conservative time, US punk maintained a brash anti-corporate, anti-authoritarian stance, with songs and visuals that condemned police brutality, US imperialism and even sexism. There was a powerful mistrust of the established music industry, with artists preferring small, independent labels and control of their own work over “selling out”.

Freedom calling

To Cobain and Novoselic, punk became a beacon of emancipation in their conservative, working-class hometown of Aberdeen, Washington. (The Teen Spirit video even includes a reference to Cobain’s time working as a high school janitor.)

But the obsession with selling out could turn into its own kind of restrictive puritanism. Alongside a general questioning of social values, there was a cynicism and nihilism expressed in depression and the abuse of hard drugs. Some used the chaotic aspects of punk as a pretext for violence, such as the neo-Nazi punk gangs that sprung up in the southern California hardcore scene.

Nevermind, Nirvana’s second album, was released on 24 September 1991. Cobain had originally wanted to title it Sheep, in reference to what he saw as the unquestioning jingoism of the American public around the 1991 Gulf War. In a song from the same period, Cobain’s musical heroes, Sonic Youth, attacked Reagan’s successor, George Bush, with the line “Yeah, the president sucks, he’s a war-pig fuck”.

Earlier that year, Nirvana had left their Seattle-based independent label, Sub Pop Records, to sign with a subsidiary of Geffen Records. This move was motivated partly by the fact that, despite its anti-commercial stance, Sub Pop failed to pay its musicians a liveable wage.

The band chose to pre-empt allegations of being sellouts in a suitably self-mocking and punk way. For Nevermind’s cover, they chose an image of a baby boy swimming to a dollar bill attached to a fish hock, a symbol of the corrupting influence of money.

Ironically, this anti-consumerist image has now become the source of a lawsuit filed by Spencer Elden, the baby whose photo was on the cover.

The 13 songs on Nevermind highlight the musical diversity of US punk, shifting from psychedelic walls of sound (Come As You Are) and howling thrash (Stay Away) to a chilling acoustic song about homelessness (Something In the Way).

Cobain’s lyrics are allusive and surreal, ironically touching on themes like narcissism (“the finest day that I ever had/ was when I learnt to cry on command”). Punk demanded relentless self-questioning, and in On a Plain he even challenges his own relevance as a musician: “What the hell am I trying to say?”

But while the lyrics are sarcastic and full of self-doubt, the music soars with supreme, delinquent glee. The sound of Cobain’s voice and guitar slamming into the rhythm section of Novoselic and Grohl, such as the lightning crack of drums that precede the unforgettable chorus of Come As You Are, is thrilling.

With a bang

Nevermind sounds heavy without resorting to machismo or posturing. It is accessible and melodic while maintaining the band’s abrasive eccentricities. Nirvana and their label thought that, at most, the album would sell 100 000 copies, enjoying the same kind of modest commercial success of artists like the Pixies and Jane’s Addiction.

Instead, within a matter of months, they would become the most talked about artists in pop culture. Buoyed by the MTV success of Smells Like Teen Spirit, the band were catapulted to a level of fame and adulation none of their friends and peers had experienced.

The media saw this as a musical sea change, declaring that edgy, alternative culture was asserting itself – authenticity versus the excessive and materialistic 1980s. In January 1992, Nevermind replaced Michael Jackson’s Dangerous album at the top of the Billboard 200, the most influential sales chart in the world.

On 11 January 1992, the band played on Saturday Night Live, smashing their equipment after a ferocious performance. Cobain and Novoselic even kissed on live television to “annoy the rednecks and homophobes in Aberdeen”.

Later that year, in the liner notes for the band’s compilation Incesticide, Cobain pleaded: “At this point I have a request for our fans. If any of you in any way hate homosexuals, people of different colour, or women, please do this one favour for us – leave us the fuck alone! Don’t come to our shows and don’t buy our records.”

But fame seemed to intensify his existing struggles with depression and addiction. The same night as their Saturday Night Live performance, he would almost die from a heroin overdose. His life would become a downward spiral culminating in his death by suicide in April 1994. The infamous “it’s better to burn than to fade away” suicide letter he left behind would morbidly be emblazoned on T-shirts and wall posters.

Commodifying dissent

The success of Nevermind inspired a cynical wave of advertising marketed to a new Generation X “demographic”. In 1992, Marc Jacobs launched a “grunge” fashion line, while Subaru released an advert that claimed its new automobiles were “just like punk, except it’s a car”.

When The New York Times interviewed Sub Pop Records employee Meagan Jasper about the “Seattle scene”, she proceeded to prank the newspaper by listing absurd made-up slang, which it reprinted without question.

Eager to find the next Nevermind, major labels offered dozens of independent and idiosyncratic musicians lucrative deals – and then proceeded to drop them when their albums failed to sell in the millions. After Cobain’s death, copycat bands like Bush, Silverchair and the woeful South African group Seether filled the airwaves with songs that stole Nirvana’s aesthetic – minus the talent and punk ethics.

In his book Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher discusses how capitalism commodifies radical dissent and independent culture by using rebellion as a marketing tool. (A perfect contemporary example is a 2017 Kendall Jenner advert that co-opted the Black Lives Matter movement to sell Pepsi.)

Related mixtape:

Fisher argued that “in his dreadful lassitude and objectless rage, Cobain seemed to have given a wearied voice to the despondency of the generation that had come after history, whose every move was anticipated, tracked, bought and sold before it had even happened. Cobain knew he was just another piece of spectacle, that nothing runs better on MTV than a protest against MTV; knew that his every move was a cliché scripted in advance, knew that even realising it is a cliché.”

And yet, in their brief, explosive career, Nirvana also advanced what Fisher calls the “promethean” and “utopian” dreams of punk and the desire for something outside the world of consumer capitalism, drudgery and alienation.

Nirvana were incorporated into the endless spectacle of capitalism, but they also tried to use it as a platform to promote an adversarial world view. From their open contempt for the music industry to their regular excoriation of bigots, they encouraged their audience to be more than passive consumers.

In 2014, Grohl said that the ultimate legacy of Nirvana was one of inspiration. “Don’t look up at the poster on your wall and think, ‘Fuck, I could never do that.’ Look at the poster on your wall and think, ‘Fuck, I’m gonna do that,’” he said.

This idea of ending the separation between performer and audience and between art and daily life animated the punk movement. It was this subculture, with all its contradictions and messiness, that gave three high school “dropouts … making minimum wage” the confidence to make one of the most indelible popular culture statements of the late 20th century.