Nakhane’s muscle memory

As the artist returns to the stage with their first live performance in two years, and an album on the way, they contemplate what this means through their look, approach and sound.

Author:

20 May 2022

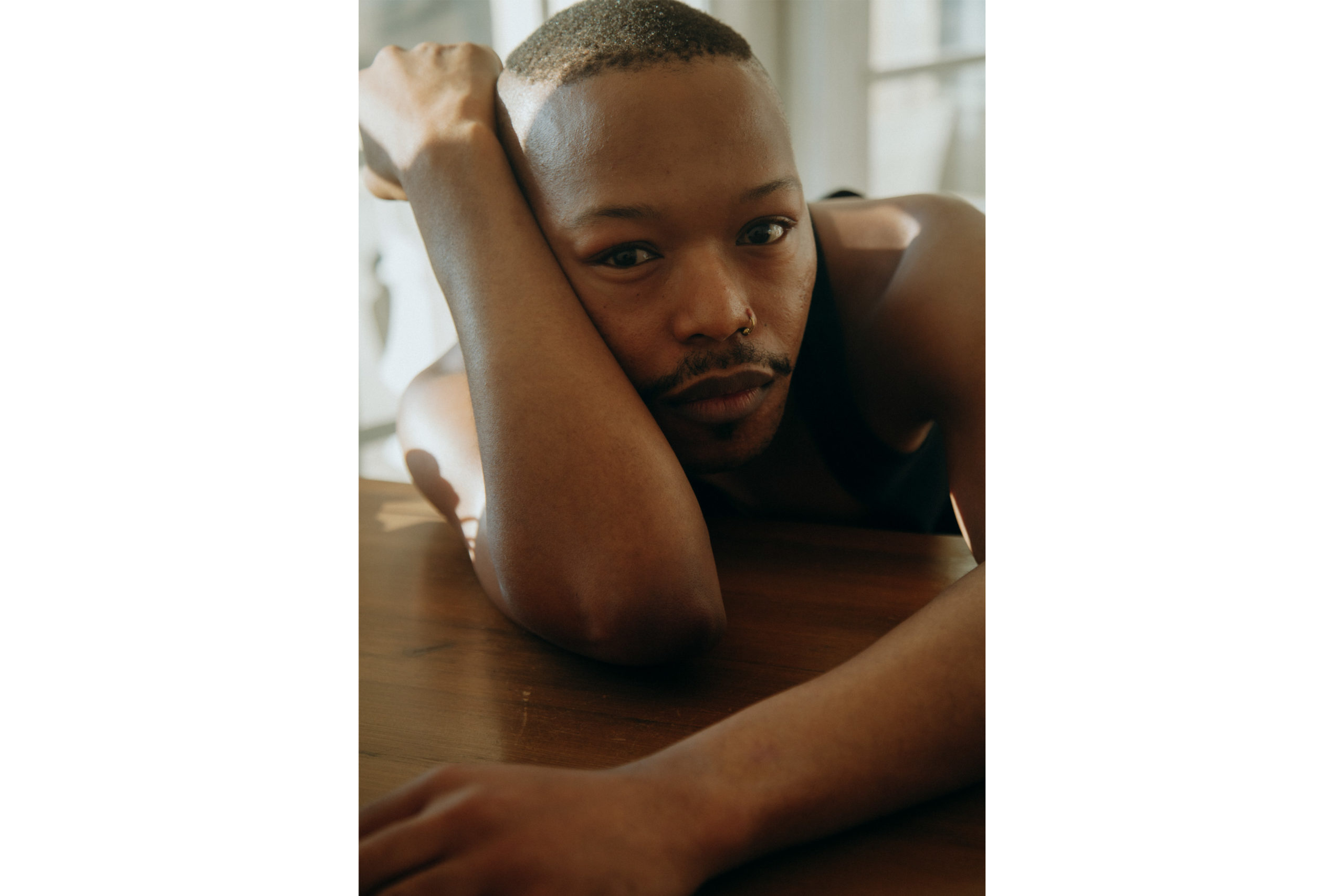

Nakhane greets me wearing “all-black-everything”. In Doc Martens, shorts and a vest, this sartorial turn is a signal: the artist has entered a new era. Walking into a minimalist apartment in Westminster Mansions, Johannesburg – a temporary home for the musician now based in New Cross, South London – their extravagant Rich Mnisi suits and elaborate Euphoria eye make-up have been replaced by something more austere: a uniform. Nakhane is, in effect, wearing time – showing how the years and the changes they’ve brought can be marked in aesthetic shifts.

For musicians, the meaning of a change in appearance is significant. It’s a telegram to the audience in all caps, declaring that a new album is on the way.

When we spoke a week earlier, Nakhane was on their way to a photo shoot for their fourth project, which follows 2018’s You Will Not Die. It was a reshoot demanded by time’s changes, too. Two years have passed since the album was completed and their vision has distilled. While initially influenced by Solange-like images of multiple bodies, Nakhane is now interested in a stripped down, back-to-basics approach.

“Remove everything and just have the bare essentials in terms of the visuals,” they explain. “And that’s going to be extended into the shows as well, no longer flowing clothes, more streamlined, hard” with “a sense of rhythm and military precision”.

The multihyphenate – actor, musician and writer – has returned to South Africa to headline Baseline Live, their first show in more than two years, and they are nervous.

“We are a very honest country when it comes to performance. If it’s shit South Africans will tell you. They are not going to clap just nje because they like you. So it’s a baptism by fire, I’m getting back into the groove of things”, they say.

The inner engine

The last time I saw Nakhane was at an interview marking the culmination of their Don’t Die Babes world tour, with a performance in Maboneng, Johannesburg. Over the years, having insight into the person and process behind the product – as writer, contemporary and friend – has meant the rare opportunity to witness not only output, but also the (at times) complex and crushing mechanics of the creative process when plugged into the capitalist machine. To witness, in other words, a life.

Within this, Nakhane’s metaphor for approaching the new show feels apt. It’s a “tearing away the skin, to see how the engine works”.

They go further, explaining that You Will Not Die was “so soft and feminine, and I felt like I pushed that to a place where I was no longer interested in exploring that anymore. I wanted to explore something more violent, because as much as we encourage each other to be soft”, we forget that we live in “a very violent world”. Survival, for Nakhane, means cultivating “an image of hardness” that “does not mean that you are not kind, or you don’t love”, but that “you are willing to go to any depths to protect what you love, or who you love, and yourself”. In other words, being queer.

“And so I wanted to explore nations, belonging, armies, the military, masculinity,” says Nakhane. “I’ve always run away from it because I just found it to be toxic, dangerous … so I’m asking myself what is [masculinity] to me?”

These questions pulse through their larger body of work, too – asked anew each time. Their last album, for instance, opened with the track Violent Measures. Nakhane’s musical projects consistently return to the same themes – expanding considerations of queerness, familial relationships, Christianity, love, sex and self. Their work feels like an extended study in self-portraiture.

A different way of seeing

Understood in this way, their next project is less dramatic turn than shift in perspective – a way of seeing the same terrain from a different vantage point. And within this, everything is a site of subversion, subject to exacting critique and consideration – including clothing.

Nakhane’s “uniform” is punctuated by a nose ring, moustache and multiple piercings. It’s a signal of a deeply queer masculinity. As I share this, they cheekily respond that they were going for “1970s porn star” – with a wink – before expanding on their new look’s deliberate and studied intent.

Related article:

Their approach to the themes of the upcoming album and view on aesthetics invoke a contemporary who feels like their kin: Ocean Vuong. The Vietnamese-American poet once riffed on wearing a singular long earring, as both a nod to his mother as well as a declaration of his queerness; “a thesis of myself”. There are thematic resonances in the considerations of armies, war, masculinity and violence – the current of Vuong’s novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous and poetry.

Vuong and Nakhane circle similar questions as artists living alongside each other, trying to understand themselves and this world, to live in it and ultimately to express this experience in art.

“I’m giving you Zadie Smith,” Nakhane retorts.

Working the muscles

As they pose for photographs, their reference to the author is simultaneously a joke and a reminder that the two have the same literary agent.

Nakhane’s literary approach to lyrics, which read with the pithy sensibility of poetry, underscored by sharp critique, is a practice honed through many modes of writing, including songwriting, essays and a novel. Arrestingly beautiful and poignant in song, as Kwanele Sosibo astutely critiqued, their first novel read more like “a statement of intent rather than a fully fleshed-out work”, “carried by [Nakhane’s] poetic, sensuous prose rather than by attention to storytelling mainstays such as a narrative arc”. It felt like a promise.

Their music is a dazzling place where a sentence is a thesis. Lyrics such as “Oh boy, white Jesus loves you now. Much more than he’ll ever love me” and “Desperate times call for stolen pleasures”, or where the simple change from “I found you in the excess” to “I found you in the absence” are a Black queer life story. They present biography woven into histories of the church, colonialism and an indictment of the present. Nakhane sings a song of themself and their work is a powerful form of autotheory: a way of theorising through the personal.

Writing this project, Nakhane is interested in muscle. “But not like Arnold Schwarzenegger muscle,” they explain, it’s more “mobility and stretching yourself to see what you are capable of”, where creating music is a muscle “that you have to work out”.

“Every time I write a new album, I find a new way to write,” they say. “With Brave Confusion it was acoustic guitar, with You Will Not Die it was the piano, and with this one it was me programming percussion, beats and then writing lyrics on top of that, and music on top of that.”

A harder story

While their work has always been vulnerable and personal, it was previously constructed by placing “metaphor upon metaphor upon metaphor”. They first worked from an image, considering how to make it emotive and to “suggest a mood. Now I’m like here’s the story, which is harder than I anticipated,” they say – aiming to be more direct with this project, with less suggestion and obfuscation.

“I think I’ve grown into myself, I have a much stronger sense of who I was when I was writing the album, which is a long time ago,” they say, laughing.

As I ask if the time that has passed since finishing the album means they feel removed from it, Nakhane says: “That’s what I was afraid of. When you have something waiting for so long, you think, oh god, by the time it’s out will I still care for it?” But they do care, deeply. “I still love it, because I’ve never been this involved before.” They’ve engineered, produced, arranged and more on this project, which is simultaneously their most collaborative.

Related article:

As Nakhane plays tracks from the new album on a small portable speaker, the drums hit first, pulsing and electronic, followed by the familiar layered choral vocals. As Nakhane navigates the same themes, the change in who they are, how they view their past and present, is expressed in a sense of newly narrowed eyes and insistent talking back stacked into uptempo rhythms – poignancy, humour and pain alongside play.

“Disco was a sad genre made by marginalised people who still wanted to have a good time,” they remind us.

Back on stage

The light is fading. As Nakhane poses for the last images, Johannesburg seeps into sunset behind them. Preparing for the upcoming show, “there is a sense of stretching out the muscles, seeing if they still have the pliability, the range” after years away from the stage.

“Covid was hard for creatives. Well, for everyone, but you know it really whacked us creative people, particularly performers, because who are you now that you don’t have that thing that defines you so much?

“I get so much of my self-worth from being on stage, from performing, from feeling like I’m exceptional, and that made me look into my childhood, like why, why do I feel like I can only be loved if I’m performing? But also understanding that that’s also my make-up as a person. It can be healthy and it can also be dangerous, it’s how you manage it.”

They used to live here, in Westminster Mansions. Returning to the building, the stage, and to the album cycle, is also returning to themself – asking the questions that come with staring at your reflection through song and place.

Within this, their new aesthetic is a metaphor; a form of visual poetry.“I just want to be a good musician. I want to be a better musician – that’s all I’m really interested in – a better performer,” they say, “which is why I’m trying to strip away the layers.”