Mother Earth is a victim of gender discrimination

In Text Messages this week, if the world started ‘thinking like women … it would end violence against women and children’ – and against the planet.

Author:

11 November 2021

It is telling that the single most significant piece of writing about the harm that humankind inflicts on nature was written by a woman. Portions of this book first appeared as lengthy articles in The New Yorker weekly magazine. Then, in 1962, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring hit the bookshops.

A scientist with the ace reporter’s eye for telling detail, the nature writer’s ear for the Earth at work and rest, and the pantheist’s respect for all living things, Carson shook the world out of its easy relationship with the chemical mass-warfare being waged on insects, weeds and fungi. All the easy nostrums of the agricultural industry were in Carson’s sights, from DDD to its close relatives DDT and DDE, the herbicides 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T, and organic phosphates, among many others.

In the noxious atmosphere of today, where the careful work of responsible scientists is routinely disparaged by conspiracy theorists and hysterical ignoramuses, Carson’s book would have had an interrupted arrival and bumpy reception. In the marginally saner world of the 1960s, with the memory of a world war and two atomic bombs that obliterated tens of thousands of people still fresh in the mind, there were fewer labelling cries of “Alarmist!” (Although the chemical-industrial complex repeatedly uttered that epithet.)

Related podcast:

Carson pursued her case dispassionately, shining a forensic beam on the crimes against nature and by extension humankind committed by the excessive use of pesticides, insecticides and herbicides. The birds of the air, the fish of the sea, the quadrillions of living things on the surface of the Earth, including humans: all were at desperate risk.

Carson ended her brilliantly lucid demonstration with an advocate’s closing argument of eloquent force: “The ‘control of nature’ is a phrase conceived in arrogance, born of the Neanderthal age of biology and philosophy, when it was supposed that nature exists for the convenience of man. The concepts and practices of applied entomology for the most part date from that Stone Age of science. It is our alarming misfortune that so primitive a science has armed itself with the most modern and terrible weapons, and that in turning them against the insects it has also turned them against the Earth.”

A man’s world

Today we are even further on the road to perdition than in 1962. The obliteration of so many pollinators means more humans in more parts of the world will face the terrible slide from food shortages to hunger to famine. Soaring temperatures and freak weather will play havoc with farming, and it is women and girls who will be most affected because they are on average more dependent on subsistence farming.

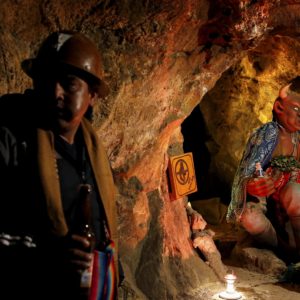

Given that climate collapse worsens gender inequality, it was cheering to see that the COP26 summit devoted a day to discussing gender equality. Probably the most quotable quote came from Angelica Ponce, executive director of the Plurinational Authority for Mother Earth in Bolivia, who said, “The world as designed by men has destroyed many things. The world should begin thinking like women. If it was designed by women, it would end violence against women and children.”

Related article:

But despite the huffing and puffing, promises and commitments that the media drip-fed from COP26, it is difficult not to think of it as a colossal disappointment. Before the ink had dried on some agreements, signatory nations were readying to renege, none in so spectacularly infantile a style than Indonesia, which complained that the anti-deforestation paper it signed was too tough on it.

Let’s leave COP26 aside because a profound text on this very subject of ecology, climate and care for the Earth already exists – and says so much in so few pages. Laudato Si’ is the encyclical letter Pope Francis published on 24 May 2015. Its title means “Praise be to you” and its subject is “On care for our common home”. Its 183 pages are free to download and provide a singularity of vision that the babel of Glasgow cannot.

Problems and solutions

Francis begins by saying, “Mother Earth, who sustains and governs us … now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her.” He then sets out problems and solutions. To give a sense of its breadth and depth, here is a breakdown of its contents.

Chapter one, “What is happening to our common home?”, looks at pollution, climate change, waste, the throwaway culture, water, lost biodiversity, decline in the human quality of life and global inequality.

Chapter two, “The gospel of creation”, offers a biblical perspective, including a beautiful section titled “The message of each creature in the harmony of creation”.

Related article:

Chapter three, “The human roots of the ecological crisis”, examines technology, the globalisation of the technocratic paradigm, and the crisis and effects of anthropocentrism.

Chapter four, “Integral ecology”, ranges from environmental, economic and social ecology through cultural ecology and the ecology of daily life to the principle of the common good and justice between the generations.

Chapter five, “Lines of approach and action”, suggests a realistic programme based on dialogues about the environment in the international community, new national and local policies, transparent decision-making, politics and economy working for human fulfilment, and religion and science talking to each other. Very refreshing is the pope’s pragmatism and emphasis on viability considering these are often sadly lacking in those secular experts skilled in analysing and decrying the establishment and the status quo, but unable to offer a comprehensive and achievable counter-plan.

Chapter six, “Ecological education and spirituality”, explores a new lifestyle, preparing a covenant between humanity and the environment, ecological conversion, joy and peace, civic and political love, and the relationship between all creatures. Together with the second chapter, it is the most religious aspect of the encyclical.

Related article:

Francis gives the reader 246 theses. The following from chapter six, under the section “Towards a new lifestyle”, will surprise many.

“203. Since the market tends to promote extreme consumerism in an effort to sell its products, people can easily get caught up in a whirlwind of needless buying and spending … This paradigm leads people to believe that they are free as long as they have the supposed freedom to consume. But those really free are the minority who wield economic and financial power. Amid this confusion, postmodern humanity has not yet achieved a new awareness capable of offering guidance and direction, and this lack of identity is a source of anxiety. We have too many means and only a few insubstantial ends.”