Migrants face mental health crisis amid lockdown

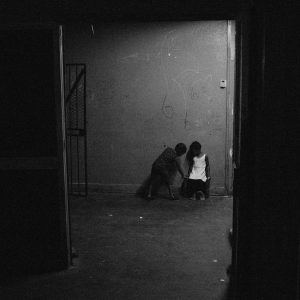

The ongoing lockdown in South Africa has confined vulnerable refugees and asylum seekers to tiny rooms in which past traumas and hunger haunt them.

Author:

9 June 2020

Esther Bikombo’s* life in South Africa has been one struggle after another. But the past two months during South Africa’s extended lockdown to fight Covid-19 have become nearly unbearable for the single mother of two.

Locked up in a tiny room with her children, the younger of whom has a severe physical disability, Bikombo, 38, has felt her mental health deteriorate quickly. Seeing the military on the streets has provoked vivid memories of the horrors she had faced in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Related article:

Bikombo fled the DRC in 2007 after an attack on her family. She was sexually assaulted by rebels from the military group M23. They hacked her brother and mother to death with machetes in front of her. The use of rape as a weapon against women in the DRC’s ongoing conflicts has long been a concern, with Human Rights Watch reporting that in 2008 alone nearly 16 000 rapes were reported in the country.

“In the east of the country, a battleground for government troops, militias and foreign armies, sexual violence is practised systematically by many fighters,” Human Rights Watch said in 2009.

But this was not the only time Bikombo was raped. As she travelled through many African countries – including Burundi, Tanzania and Zimbabwe – to seek refuge in South Africa, she was sexually assaulted by men who offered to help her.

Before Bikombo’s family was attacked and she was forced to flee, harassment from the government’s security forces was a common occurrence for them. The family lived in fear because her father, a journalist, was an outspoken critic of former president Laurent-Désiré Kabila.

“I have not been able to sleep. I have been very scared,” Bikombo recently said while sitting in a room at the Sophiatown Community Psychological Services (SCPS) in Bertrams, Johannesburg, where she receives counselling and other help.

“I have been thinking too much … lots of questions that don’t have an answer. It makes you go back to remember everything that happened to me.” On top of the trauma of seeing soldiers on the streets again and having flashbacks of what happened to her, Bikombo, who is unemployed, worries about how she will feed her children.

“It makes life unbearable because you have to work to provide as a mother, but there is no way I can provide [for] or feed the children. It makes life hell for me,” she said.

Effects of stress and anxiety

Federica Micoli, legal and advocacy officer at the SCPS centre in Bertrams, said the majority of the 50 families with migrant or refugee backgrounds to whom the organisation provides assistance have been dealing with “a huge amount of stress”.

“Well, honestly talking about our clients, I would say all of them [are struggling]. They have a huge amount of stress because they don’t have food. They’re all stressed because they’re threatened to be evicted because they can’t pay rent. I would say all of them. And then there are those who need specific medications but they can’t get it, and it makes the situation worse.”

Micoli said the mental health crisis facing refugees and asylum seekers as a result of the extended lockdown exposes all the fears they have – from fleeing their countries to not being able to provide the basics they need for themselves and their families in South Africa.

“We are trying to get a donation of washable nappies because the mothers don’t even have those. So you can imagine how stressful it is for these mothers,” she said.

The Psycho-Social Rights Forum, a consortium of non-governmental organisations that offer psycho-social support to refugees and asylum seekers in South Africa, said it was concerned about “the toll that the lockdown is having on the mental health of our clients”.

Related article:

The forum said asylum seekers and refugees generally displayed “amazing resilience” in leaving their countries and being forced to make a new life elsewhere. “However, since the lockdown, hundreds of thousands of families find themselves locked up in rooms that they share with other destitute people, unable to provide food [for] their children.

“Many of our clients manifest symptoms – constant headaches, body aches and high blood pressure – that can be related to the need for an unrelenting vigilance in their daily lives. In the isolation of their dwellings, memories of war and persecution, which had been skilfully managed by the daily struggle for survival, have come back to haunt many of our clients. This leads to the feeling that they will never be free from those ghosts,” the forum said.

“During this time, the sense of uprootedness and of not belonging is also enhanced by the fact that migrants are de facto, even if not formally, excluded from the government food distribution programmes and social grants. Renewed anxiety around xenophobic attitudes is also exasperated by ministers who suggest that, after Covid-19, the economy should exclude foreigners so that South Africans can recover from their losses.”

Nowhere to call home

Joseph Beya, 20, came to South Africa when he was four years old, after his family had fled the DRC. “Basically, I don’t know a lot of that side. But I was told stories of the war and why we came here,” he said.

As a young refugee in South Africa, xenophobic comments from peers at school were always present. And in September last year, the xenophobic attacks that swept through Johannesburg landed right on his doorstep in Malvern, east of Johannesburg.

“It’s been tough. I wouldn’t say it is easy for anyone when you are going to something new. It’s never easy learning how people act knowing that you are from another country. They treat you differently,” he said.

“I’m friends with mostly South African kids. I keep my circle small. I do that because I want to fit in and have a sense of belonging at least. If you have South African friends it is a bit better, because some of them do understand what’s happening to you. At school, I was called names. And just hearing how people talk about people from other countries – it does have an impact on you, and it makes you feel like you don’t belong here.

“I have been living in Malvern for almost all my life, and I am sure you know what happened there last year with the attacks. They were throwing things where we were living. I heard some people jumping over [the wall] but the police came before anything could happen. I was shaking,” he said.

Beya, his 14-year-old sister and their mother survived the xenophobic attacks unharmed. But his world came crashing down when one of his best friends was shot dead outside his house, on Christmas Day last year, after visiting him.

Related article:

Being confined to the small room he shares with his mother and sister during lockdown, Beya said all the thoughts and feelings came rushing back. “Lockdown has been tough. Physically, emotionally, even financially, it’s been hectic. Physically because the right to be free and to go out has been taken away from us, which I feel is one of the only rights foreigners have in this country – the ability to move around,” he said.

“When you are stuck inside you go through a lot of thoughts. That affects you emotionally and psychologically. With our parents who come from places where there is war, we can see the psychological effects on them. Even seeing a soldier they freak out, because they remember what used to happen in war.”

Unable to register for tertiary education because of his documentation status, Beya is left watching as his peers carry on with their education and careers. He launched his own clothing brand, Yasuka, in part honouring his friend who was killed, and trying to make a living to help his family.

“With me, my brand has been put to a halt. I just started it last year … but now I’ve used the money I’ve been making to try and get my family through this time,” he said. “With lockdown, when I am stuck inside [the house] I am full of thoughts. Sometimes depression kicks in and you lose it and you feel like why am I here? I am a burden because if I was not here, if mom was maybe alone, things would have been better.

“I am the first born and I am supposed to be making a plan for the family, and not being able to do that makes me question myself as well. It makes me think maybe I am not cut out for this – ‘you are letting everyone down’. It’s hard to believe [that I am not a failure] at times because people my age are doing things, making things happen. That’s how I feel,” he said.

Karen Weissensee, a counsellor at the SCPS centre and a social worker with more than 30 years’ experience, said she has seen “lots of hopelessness”.

“Lots of this is unbearable. One mama had entire pieces missing from the conversation we had the day before, some really regressive stuff. The physical stuff – terrible headaches, ulcers … The ulcers are worse because there is not enough food and you are stressed,” Weissensee said.

Related article:

“People are locked in their rooms and they are terrified. They are both terrified by the current situation and what they have been through historically that is now coming back. And when you are living with children – children don’t understand there is no food, there is no money. So [people are] getting angry and frustrated with the children as they are challenged with their inability to provide.”

Weissensee said the fear of the police and army is always there, but it has been exacerbated by seeing them patrolling the streets. “There is a fear that they have regressed. I think and I hope we can still regain that ground.

“Some of them have made steps into independence and now all of a sudden they are back having to ask for help with food or rent, feeling humiliated having to beg … The lockdown has caused serious anxiety, serious depression, serious irrational thinking. I have had to do some extra containing [work], telephonically, of people who are just not managing.”

*Not her real name.