Max Coleman was a champion of human rights

The arrest of his son in 1981 turned Coleman into an activist and anti-apartheid campaigner, leading him to an Order of Luthuli award.

Author:

27 January 2022

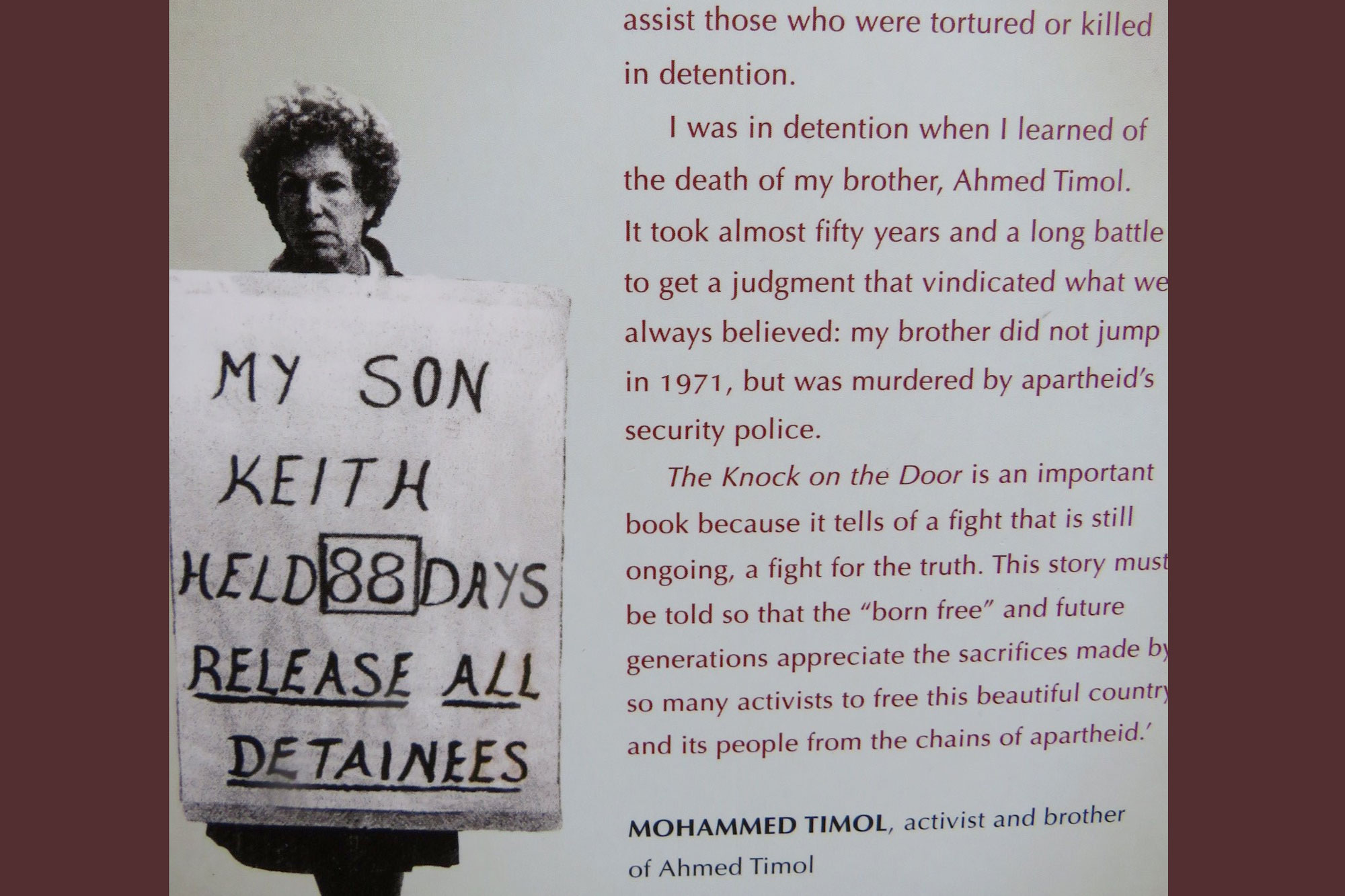

Max Coleman, who died at the age of 95 in Johannesburg on Sunday 16 January, and his wife Audrey Coleman were driving forces of the Detainees’ Parents’ Support Committee in the 1980s.

The committee was initially an ad hoc support group. The Colemans started it with the parents and family members of other political detainees arrested by the security police in 1981, based on duped Barbara Hogan’s “close comrades” list.

It grew into one of the most visible community-based organisations in the country. The committee raised awareness about what was happening behind closed doors at police stations, improved the conditions under which detainees were held, and offered material, legal and social support. Using Coleman’s rigorous research methods and meticulous record-keeping, it collected information about nefarious weapons of repression. These records are vital evidence of what happened during the most violent period of apartheid.

Wagging the tail of the dog

Before the 5am knock on the door of their suburban Johannesburg home on Saturday 24 October 1981, the Colemans were a middle-class couple focused on raising a family and making a living. Morally opposed to apartheid, they were inactive members of the Congress of Democrats in the 1950s and remained philosophically concerned but politically “dormant” after the Sharpeville massacre in 1960.

The Soweto Uprisings of 1976 confirmed their unease though, Coleman told researcher Jocelyn Hellig in 1995 for the book Cutting Through the Mountain. “Our sons had become involved in student politics … and they started educating their parents.”

The security police were looking for their son Keith, whose name was on Hogan’s list. But he was neither at his parents’ home nor the flat in Yeoville that he shared with his friend Clive van Heerden.

Keith decided to turn himself over to the security police and Coleman accompanied him to the notorious John Vorster Square police station on the morning of Sunday 25 October 1981. His father told arresting officer Captain Andries Struwig that “if anything happens to my son, I will hold you personally accountable”, Keith recalled in an interview for The Knock On the Door: The Story Of the Detainees’ Parents Support Committee (2018). “And I believed him, absolutely. But I also saw that Struwig believed him. This big monstrosity of a human being looked at my father and at that moment he was scared.”

‘An immediate attraction’

Coleman was born in South Africa in 1926. His father Sam Coleman was born in Kovno, Lithuania, but only lived there for a year before immigrating with his family to Ireland. Sam, the son of an Orthodox Jewish family, fell in love with Louise Wright, an Irish Catholic. Realising that neither of their families would accept their relationship, they ran away to South Africa in 1925. Coleman told Hellig that he grew up “always uncomfortable with the racial segregation of SA and would often say that the Nationalists didn’t invent apartheid, they only perfected it”.

He became politically active while a student at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) in the 1940s, before he left South Africa to further his postgraduate studies in chemical engineering in England. In London, he shared a flat with his student friend Gerald Goldman, whose younger sister Audrey, Coleman had first met when she was a teenager.

Related article:

On his return to South Africa in 1953, Coleman met Audrey again. As she described it to Hellig: “I had, in the meantime, grown up and there was an immediate attraction.”

The couple married that year and Coleman took a job as a chemical engineer before later going into a chemical and photographic business. Audrey gave birth to their first son Neil in 1956, and raised him and three more sons over the next two decades. When their third-born Colin began high school, Audrey told Hellig, “it was time, as a privileged white, to put something back into the community and I joined the Black Sash”.

Meeting rooms

At the time of Keith’s arrest, Coleman was in charge of a successful business that employed around 500 people at its height. Although he drove past John Vorster Square on the highway every morning and was aware of its reputation, he had never been inside the building until that morning in 1981. It was the moment that saw Coleman become an activist and anti-apartheid campaigner – and it defined the rest of his life.

The Colemans were among the parents, family members and political comrades of the dozens of activists arrested in raids across the country. They began to meet at Wits University in rooms anthropologist David Webster booked for the purpose soon after Keith, Auret van Heerden, Liz Floyd, Neil Aggett, Emma Mashinini, Prema Naidoo, Firoz and Azhar Cachalia, and others were detained. They called themselves the Detainees’ Parents’ Support Committee in affinity with Argentinian group the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo.

Using their connections in the privileged world of white, middle-class society and liberal organisations, the Colemans helped parents get information about their legal rights and the places and terms of their relatives’ detention, and deliver food parcels and other items to detainees.

When Aggett died in detention, the Colemans were at the front of a march by the parents’ committee to John Vorster Square, where they demanded and were granted visits to their relatives. As Coleman recalled for the Sunday Times Heritage Project in 2007, Aggett’s death “was a great shock for the authorities … the publicity for them was absolutely negative. That had the effect of breaking through and setting up visits for all the detainees’ relatives … There was no way they could disagree to that, so that started a whole new era.”

Going national

By the time Keith was released from detention in April 1982, the committee was mushrooming into a national organisation. It increasingly drew the ire of the apartheid government, which denied the organisation’s regular condemnation of detentions in local and international newspapers despite the painstaking records the committee provided to reporters.

Shortly before the announcement of the first state of emergency in 1985, the committee moved into offices in Khotso House in downtown Johannesburg. “Within the first two weeks, there were 10 000 people detained and … suddenly we had this huge problem of recording all these detentions and responding to all these families,” Coleman said of this period for the Heritage Project.

The security forces targeted members for their involvement in committee activities, but it was a fundamental source of support for thousands of families during the turbulent 1980s.

Webster’s assassination in 1989 was partly the result of him being a committee organiser, and the much publicised “tea parties” he hosted to allow parents and activists to circumvent the ban on political gatherings.

Agents of the apartheid government bombed Khotso House, which also housed several other anti-apartheid organisations, in August 1988, under orders from then president PW Botha and longtime committee antagonist and then minister of law and order Adrian Vlok.

Human rights champion

Coleman was appointed as a commissioner of the newly established Human Rights Committee (HRC). The umbrella body sought to continue the work of monitoring and documenting state repression that the committee had spearheaded before its banning in February of that year.

By the time of its unbanning in 1990, the system the committee had been set up to expose and oppose was beginning to be dismantled. Then ANC secretary general Alfred Nzo thanked the committee for undertaking the “mammoth task” and “tireless work” of ensuring “that the South African people and the international community became conscientised and politicised about the inhuman, repressive apartheid system. We will always be indebted to you.”

As head of the HRC, Coleman helped raise awareness about the extent and nature of the political violence that swept the country in the build-up to the first democratic elections in 1994. He went on to serve as one of the first commissioners of the South African Human Rights Commission.

Coleman and his wife were awarded the Order of Luthuli in Silver in November 2021, for their contributions “to the fight for liberation and the promotion of human rights through active involvement in lobbying”. The couple were honoured, but warned that “the freedoms South Africans fought for are not the freedoms enjoyed today. Instead, unemployment, poverty, racism, inequality and violence are alive and well … State capture and thuggery have corrupted not only the state but the minds and soul of the ANC. They have attempted to steal the freedom, vision and hopes of the nation. They cannot be allowed to succeed.”

Related article:

They urged President Cyril Ramaphosa to rid the ANC of corrupt elements and restore the state to its “historic duty to put South Africans first … It is to the future generations we now look. We hope, and believe, that the Coleman grandchildren will be part of this future. We hope, too, that all South Africans will embrace this future which so many died and struggled for.”

Coleman is survived by Audrey, his sons Neil, Keith, Colin and Brian, and his grandchildren.