Marital rape lawsuit unsettles India’s men

The law that allows husbands to rape their wives without fear of prosecution is being challenged. Angry men are threatening a marriage strike while the state remains reluctant on legal reform.

Author:

8 March 2022

A social media campaign calling for a marriage boycott after India criminalised marital rape has shed new light on the deep-seated patriarchal biases in the country’s legal system.

The campaign was in response to a lawsuit seeking to make “non-consensual intercourse and sexual acts” with one’s wife part of the offence of rape in India’s penal law. The high court in Delhi resumed hearing submissions on 11 January from rights groups challenging the constitutionality of a marital rape exception in Section 375(2) of the Indian Penal Code, which gives married men immunity from prosecution when they rape their wives or are accused of doing so.

As the high court conducted hearings on the petition to criminalise marital rape, the hashtag #MarriageStrike surged on Indian social media by 20 January. Thousands of tweets were sent in reaction with some pledging not to marry, saying it would make marriage a dangerous institution for men.

Opposers of the lawsuit say criminalising marital rape will undermine the Indian family system and that the change in law would be used by women to “wrongfully accuse” men of rape. The Save India Family Foundation (Siff), the lobby group formed in 2005 that launched the Twitter campaign, said criminalising marital rape would put men at risk of facing frivolous criminal charges.

Related article:

“Men don’t want to get married because their human rights are not getting protected,” said Siff co-founder Anil Murty. Before the hashtag became popular on social media, Murty said the phrase “marriage strike” was used to convey discontent with the difficulties of obtaining a divorce.

Men’s rights activists took to Twitter again on 26 January to declare that there were “large-scale violations of civil liberties and human rights in the name of women’s empowerment” and that men are treated as “second-class citizens” in the country. They used the hashtag #NoRepublicDay4Men in their posts. Republic Day falls on 26 January in India and is the day on which the country’s Constitution first came into effect.

The Siff-led rants did not go unchallenged. Many Twitter users mocked those who said they would boycott marriage if the government criminalised marital rape, saying they hoped such men would go on strike indefinitely as it is perilous to marry a man who does not comprehend the notion of consent.

“Consent is among the most underrated concepts in our society. It has to be foregrounded to ensure safety for women,” Indian National Congress leader Rahul Gandhi tweeted in support of criminalising marital rape.

“Behind the trend were angry and angst-ridden men who believed that their futures were being determined by feminists who were out to destroy the fabric of society by undermining the institution of marriage,” wrote journalist Harini Calamur. “But behind the inadvertent hilarity caused by the trend and the response to it lies a very serious issue – does sexual consent exist within a marriage?”

Cultural norms

India is one of three dozen nations in which marital rape is not a crime. Indian rape law excludes sex acts between a man and his wife, an exemption that dates back to colonial times. “Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife, the wife not being under 15 years of age, is not rape,” underlines Section 375(2) of India’s penal code.

This effectively means that a man having “non-consensual sex” with his wife who is above 18 years of age cannot be charged with the laws pertaining to rape. If a woman says no to sex with her husband and if he sexually abuses her, the man will not be charged with rape. He can be charged with domestic violence and other non-sexual offences.

With the emphasis on the need for consent, even among couples, the high court judges are now deliberating on petitions requesting amendment to the existing rape legislation, which considers “non-consensual sex” by a husband with his wife an “exemption”. The petitions have been submitted by the RIT Foundation and the All India Democratic Women’s Association.

Related article:

The marital rape exception has been challenged on the basis that it violates the fundamental rights of married women, including the Indian Constitution’s Article 14 (which provides for the right to equal treatment by law) and Article 21 (which is for the right to life and personal liberty).

Karuna Nundy, a lawyer representing two petitioners, told the court that the exception is unconstitutional as it gives primacy to the institution of marriage over the individuals in the marriage. “To grant immunity in situations when rights of individuals are in siege is to obstruct the unfolding vision of the Constitution,” she said.

Senior advocate Rebecca John, acting as amicus curiae (a friend of the court) in the case, argued that a married woman can be subjected to sexual intercourse without her consent and that is rape. She said the penal code’s exception provision must be viewed as “an instrument of oppression”. This is because it favours the conjugal rights of the husband and is based on the doctrine that, by getting married, a woman grants irrevocable sexual consent to her husband.

In its submissions to the court, the Indian government opposed any changes to the marital rape exemption in the law. It said the country should not “blindly” follow Western nations in criminalising marital rape, because that would have far-reaching sociolegal implications.

Related article:

Reaffirming its 2017 position, the government said there is a great variation in the cultures of Indian states and that a meaningful consultative process with various stakeholders, including the state governments, was needed.

In an affidavit filed to the court in August 2017, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi maintained that marital rape could not be added as an offence to the Indian Penal Code as it could have a “destabilising effect on the institution of marriage”. The high court in Delhi asked the Modi government on 21 February for its clear standing on the matter. The government had sought more time to submit its response and had asked the court to defer the hearing of the petitions – requests that were not granted.

When asked earlier this month about the central government’s position on marital rape, Minister for Women and Child Development Smriti Irani told the Indian Parliament that branding “every marriage as violent and every man as a rapist is not advisable”.

Historic fallacies

More than 30% of women aged 18 to 49 report having experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of their spouse, or both, according to the National Family Health Survey – 5, 2019-2021. The average Indian woman is 17 times more likely to experience sexual violence from her husband than from anyone else.

The prevalent tolerance and approval of marital rape – that women give up the right to say “no” when they marry – is intimately tied to the position of women in Indian society. This inequity stems from deeply held beliefs about the role of women in Indian families. Patriarchal attitudes are also reflected in the spousal violence prevalent in the country.

The common law origins of marital rape immunity can be traced back to 18th-century English judge and jurist Matthew Hale. “The husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful wife, for by their mutual matrimonial consent and contract the wife hath given up herself in this kind unto her husband, which she cannot retract,” he wrote.

In traditional Hindu law, marriage was a sacrament. Fathers had a religious obligation to marry off their daughters before they reached puberty. When the Indian Penal Code was enacted in 1860, it fixed the age of consent for girls at 10.

Related article:

It wasn’t until 1890 that rape inside marriage was considered legally, after 11-year-old Phulmoni Dasi died after her husband raped her. This led the age of consent for sex within marriage to be raised to 12 years.

But this created a schism between reformers, who sought to use the colonial state’s authority to better the situation of Indian women, and Indian nationalists, who considered any such move the unwarranted interference of a foreign authority in the private realms of religion and the home.

The Justice JS Verma Committee recommended in its 2013 report, Amendments To Criminal Law, that the exception to Section 375 of the Indian penal Code be removed. “The relationship between the accused and the complainant is not relevant to the enquiry into whether the complainant consented to the sexual activity, and the fact that the accused and the victim are married or in another intimate relationship may not be regarded as a mitigating factor justifying lower sentences for rape,” the commission underlined.

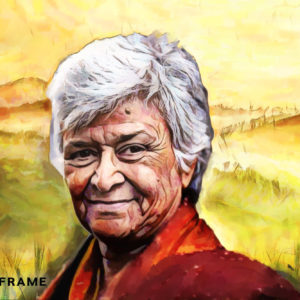

Successive governments have ignored the Verma committee’s recommendations. The state has also ignored lawyer and renowned women’s rights activist Indira Jaising’s report, submitted to the Indian Supreme Court panel in January 2016, recommending that marital rape be criminalised.