Making Black intellects central to music teaching

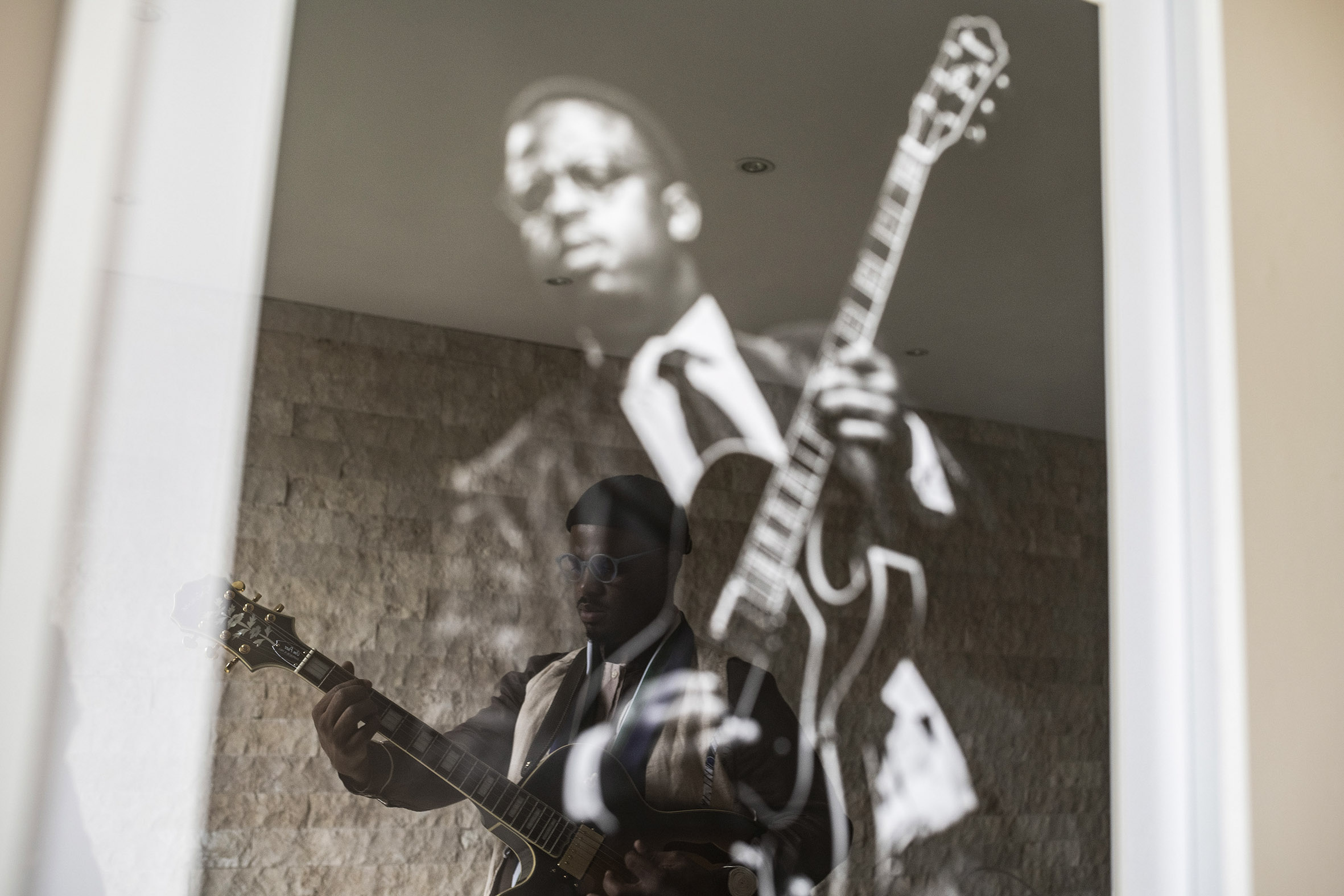

Tracing the history of guitar music and its players, guitarist Billy Monama’s new South African guitar book continues the struggle to decolonise the curriculum.

Author:

24 March 2022

Even across a computer screen, guitarist and researcher Billy Monama’s excitement is palpable. The first volume of his textbook, Introduction to South African Guitar Styles: Five Decades of Ukuvamba (Real African Publishers, 2021), is finally out. It’s the culmination of 15 years’ work: six years envisioning, investigating and planning, then the past nine packed with intensive research and learning how to publish a book – all this alongside releasing his debut album Rebounce in 2017 and continuing to develop his career as a performer and teacher.

His excitement isn’t just personal, however. For Monama, the book has been an intensely political project. “What the youth of 1976 started isn’t yet over. But now it’s an intellectual war to implement a Black curriculum.”

What initially drew Monama to this work was his experience, first as a student and then teaching. “When I was learning guitar, I learnt about BB King and Wes Montgomery, but a giant like [guitarist, bandleader and composer] Almon Memela was mentioned nowhere. I dropped out of those studies.” Later, when teaching aspiring young guitarists, he found a similar lack of materials about South Africa.

He was forced to do his own research – “I read, then I question” – and realised that not only were there no textbooks, but not even the most basic biographical or discographical information existed. “I heard names – Stanford Tsiu, for example – and looked, and found nothing … I taught a class at the University of Pretoria where most students were white and they knew nothing about Jonas Gwangwa or Dorothy Masuku. It was clear that information just wasn’t as accessible to them as Mozart and Bach.” The answer seemed obvious. “I can’t deal with all this. There’s no point of reference; it needs a book.” And he would have to write it.

That brought him face to face with other dilemmas such as the ownership of intellectual property and the hegemony of academic hierarchies, sourcing funds without strings, and relating ethically to a music community that had been neglected and exploited for generations.

Overcoming obstacles

Monama has no formal affiliations as a researcher. That proved a barrier until institutions got to understand his project and the “professors and deans” at the universities of KwaZulu-Natal, Pretoria and the Witwatersrand (Wits) as well as the Tshwane University of Technology started welcoming him. “Professor [David] Coplan at Wits talked to me about being a storyteller: what’s my narrative?”

Still, although some institutions have suggested it, he doesn’t want to convert his research into a dissertation. Academic language might limit its accessibility for “everybody who wants to know about the evolution of our music”, which is his priority.

Then “getting licences to use intellectual property that was created by our fathers” proved time-consuming and costly. It exhausted much of his budget and he faced slow communication and “being referred from pillar to post”. He had to take care to “fight [the licence holders] nicely” lest they withdrew permissions. “I understand about protecting ownership, but the irony is the money often doesn’t get to the families of who should be the real owners. I’ve had sons writing to me asking, ‘Can you help me get my father’s music back from [the record company]?’”

To shape his narrative, he had to mine liner notes, memoirs, memories and discographies for fragments of the jigsaw puzzle, see how they fitted and plug the gaps. Additionally, in eras long predating the selfie, there was almost no visual material – “band photographs in those days focused on the leader” and other instrumentalists often went unnamed.

For volume one, Monama breaks the history into three main periods: the acoustic era, the arrival of electric guitars and their influence, and then the parallel emergence of players with Black Consciousness perspectives on their playing and the development of pop music styles through the 1960s and beyond. Within that broad periodisation, he had to accommodate multiple regional guitar sub-styles, a complex exercise in joining all the dots.

For every significant track, Monama had to listen and make his own exact transcriptions. “I can’t write what I don’t know … and then I bring my guitar understanding and practicality – my ears and fingers alongside music theory – to my analysis.” He considers influences, home-grown and overseas, and what for him are important factors: feel, and the relationship between dance styles and music.

Finding sources and resources

Many of the project sponsors he initially approached didn’t understand the project and, in any case, “it seemed like it had never been done before and they didn’t want to take the risk … I spent sleepless nights working out how sponsors think.” In the end, a patchwork of funding came together, including the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, the Samro Foundation, the City of Johannesburg through its Heritage Month projects and, albeit slightly late in delivering, the National Arts Council. “And there are some donors who just love art and who’ll simply say, ‘How much do you want?’”

Because the work of historical guitarists was so poorly documented, Monama had to seek out information and photographs from families and communities. “And there was reluctance. I’ll book an interview and then they’ll cancel: ‘No, we know you guys – you write books and then you’re gone.’ Or ‘How much will you pay for a photo – you’re going to make money out of this book!’” Monama appreciates the exploitative history that contributed to this reluctance. “The families who shared information with me contributed so much. I can never take that for granted. I have to stay in touch now.”

One priceless resource has been his partnership with veteran guitarist Themba Mokoena. Monama met him through The Grazroots Project, an ensemble Monama established to perform historical South African music. “We were introduced by [pianist] Themba Mkhize and I invited him to a rehearsal. Wow! This was a guy I used to see on TV, whose records I used to transcribe. We’ve got similar influences – Marks Mankwane and Wes Montgomery, for example – and we instantly found a musical chemistry. We hardly need to rehearse. We can just get on stage and play.”

Mokoena has an encyclopaedic knowledge of other historical players, and the two musicians’ empathy has built a smaller touring duo for shows when the full Grazroots ensemble isn’t practicable. “Bra Themba never spoon-feeds me, but he teaches me so much.”

Already, Monama is posting tutorials online demonstrating the historical styles he has documented. Next on the agenda is a planned volume two, covering players active mainly after the 1960s. At present, Monama just has “a list of names on a piece of paper”, but he’s steeling himself for the next stage of patient musicological detective work he knows lies ahead.

“When I started wanting to be a bandleader, people mostly didn’t play this repertoire. But when I played it, people loved it. From that came the research to give it context. The research has got some record labels seeing the value of music they’ve neglected for years. But the real next stage will be engaging the departments of education to get the books on the curriculum to shift our children’s education further towards what Black intellects have created.”