Makhathini still taps away at sports to good effect

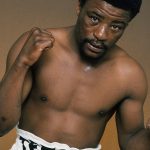

Legendary boxer Elijah “Tap Tap” Makhathini is working in the hills of rural KwaZulu-Natal to give impoverished youngsters hope.

Author:

13 January 2021

The grizzly old man sat motionless and alone on a rough-hewn wooden bench. His stoep offered pitiful shade in the 40-degree Zululand summer heat, but he seemed to dismiss it with an indifferent scalp rub beneath his leather cap.

His gaze set on the horizon. Elijah “Tap Tap” Makhathini was lost in thought. A swirl of dust on the road outside heralded the arrival of visitors. Tap Tap took them in through rheumy eyes. The white steel wool stubble on his chin stood out against his ebony skin and he looked like Santiago in Ernest Hemingway’s Old Man and The Sea, only this old boxer looked out over bushveld rather than the ocean. Nothing about the image of him betrayed his glory days.

Except maybe his hands.

The enormous, powerful hands wrapped around his knobkerrie were disproportionately large. There have been a few vain attempts to make an attraction of Makhathini’s rural bottle store off Route 66, in Habeni, a 20-minute drive from Eshowe. But the area is impoverished and Tap Tap Liquor and General Store has meagre stock to service mainly locals.

You would think nothing of the place if you didn’t know the owner or the humble boxing academy behind the store. In the 1970s, South Africans were mesmerised by the man who came to be known in the boxing world as a “southpaw sensation”.

Tap Tap Makhathini turned pro at the age of 29 and enjoyed almost a decade in the limelight. His name alone demanded attention. The plosive consonants in “Tap Tap Makhathini” conjured up images of determined fists.

Boxing in his veins

Tap Tap’s real surname is Xulu. He used Makhathini, his clan name, because some speakers who aren’t Nguni couldn’t get their tongues around Xulu. Tap Tap has a fascinating genesis. His grandfather nurtured his interest in boxing. He was forever talking about boxers. And it was he who encouraged his grandson to fill a sack with sand and pound it.

Young Makhathini went one better. He packed the makeshift punch bag with cow dung instead, and that made his hands even stronger. Just out of his teens, Makhathini got a job working for the railways as a handyman in Stanger, an hour’s drive from his home.

He was already a keen amateur boxer then and, one day, ahead of a tournament, he was chatting with friends at work. One asked him: “How are you going to win today’s fight?”

Makhathini pondered this. He took out his measuring tape and some chalk and drew a series of sketches on the factory floor, depicting the ring, the referee, himself and his opponent. “That night when I was about to get into the ring my friends shouted ‘Tap Tap’ and the name stuck. From that day on people started calling me Tap Tap – the guy who measures his moves.”

In 1971, Makhathini turned professional and found a key ally in trainer and promoter Chin Govender. This trainer-fighter relationship would flourish and earn Tap Tap many victories in the middleweight division especially. Xulu says Govender was a friend and a sharp negotiator.

“He was the best. I earned R2 a round because of Chin.”

According to BoxRec.com, Xulu had 62 bouts in his nine-year career – with 47 wins, 13 losses and two draws. His prowess as a fighter took him as far afield as Monaco. And he won against a host of prizefighters, including a memorable bout against Charlie Weir.

Related article:

In November 1976, sporting history was made when Black and white South Africans fought each other for the first time for a national title, according to an Associated Press archive.

Makhathini scored a third-round knockout of the titleholder, Jan Kies, in a ring surrounded by cameras and a crowd that included apartheid cabinet minister Piet Koornhof. A quiet, understated sportsman, Makhathini became a drawcard in the early days of non-racial boxing and was often referred to as “the peoples’ champion”.

In August 1974, he beat Brazilian Juarez de Lima. A year later, American champion Emile Griffith succumbed to his gloves. In 1976 Makhathini knocked out South Africans Victor Ntloko (in seven rounds) and then Jan Kies. In 1979, a year before he retired, he beat the formidable Charlie Weir. Makhathini says he never feared a single opponent.

He had a winning four-punch combination that ended with his sizzling southpaw. “My power? It’s my left hand. It’s like a hammer. I have wonderful memories of being in the ring.”

‘I wasn’t used to much money’

Former Daily News sports editor Mohen Govender, who is Chin’s grandson, remembers the Tap Tap phenomenon well. “I was a boy when my dad Jugoo and uncle Mahalingam went to Durban to watch Tap Tap fight Charlie Weir. They left me at home because I was too young, much to my disappointment. So I was forced to tune in to the radio broadcast.

“It went like this: ‘Charlie Weir is winning this fight and Tap Tap will need a knockdown to win.’ This was followed by an eerie silence … before commentary resumed. ‘And Charlie Weir is down and it doesn’t look like he’s going to get up’.”

Govender says his grandfather’s protégé had a devastating left hook. It left the superbly talented “Silver Assassin” sprawled on the canvas. “Weir needed several minutes of medical attention before he could be revived.”

Makhathini, now 79, recalls his magic boxing career with nostalgia. “It makes me feel so good,” he says from his verandah.

Tap Tap’s technique was to mimic boxers in the ring. Once he unnerved them he would unleash his lethal sequence of four sucker punches. “The memories fade and come back,” he said, smiling slowly and wiping a big hand across his brow.

Makhathini says he was never seduced by the success of being a champ. His rural upbringing grounded him. “You have to be disciplined. I wasn’t used to much money because I came from the farm. Fame mustn’t go to your head. People liked me and I liked being around people.”

Related article:

He only ever got into one scrap outside the ring when somebody insulted Chin because he was “Indian”. Makhathini said he settled the matter with one punch and not a single angry word.

He never felt the need to raise his hand outside the ring again. Makhathini had 23 children by five wives. Some have passed away. He jiggles the slide bolt on the door behind his bottle store. It reveals a sparse but tidy gym. He looks wistfully around the modest boxing academy.

He’s content to watch the world go by, but misses training the youngsters. It was rewarding but Covid-19 has put that on hold, he says ruefully. The old man walks with a bit of a stoop but is still sprightly. He shadow boxes and pounds the punch bag in a breathless display that would shame a man half his age.

His development work, he says, is as good for him as it is for his charges. “Training the youngsters has kept me young. If I didn’t do this I would just sit around,” he says.

Boxer Mhlonishwa Mkhwanazi says Makhathini trained him and a host of others, inspiring youngsters from around his village, most of whom had little opportunity for advancement. “Tap Tap Makhathini is a man of his word. I gained a lot of experience through him. He is a very patient man who has taught many young ones,” Mkhwanazi said.

He and Makhathini have worked together since 2001, scouting for talented young boxers and training them. “His gym is open to anyone who wants to show their skills. We have trained many champs.”

Mkhwanazi says he is still learning moves from Makhathini. “He’s old school. His style is unique.”

Zweli Ntuli from King Cetshwayo Olympic Style Boxing Association describes Makhathini as “amazing”. “Tap Tap is always encouraging youngsters. He is at every tournament, motivating participants. He accommodates everyone. As old as he is, if he had the support of the government, he could help take boxing in KwaZulu-Natal to the next level,” Ntuli says.

Local businessman Richard Chennells praises Makhathini’s work. “Any initiative that offers hope to people in poverty is cherished. This area isn’t dire. People look out for one another, but every person with a social grant or a job ends up supporting between six and eight people.

“I have heard about Tap Tap’s academy. Any sports development or a skills centre, no matter how small, has a huge impact here.”