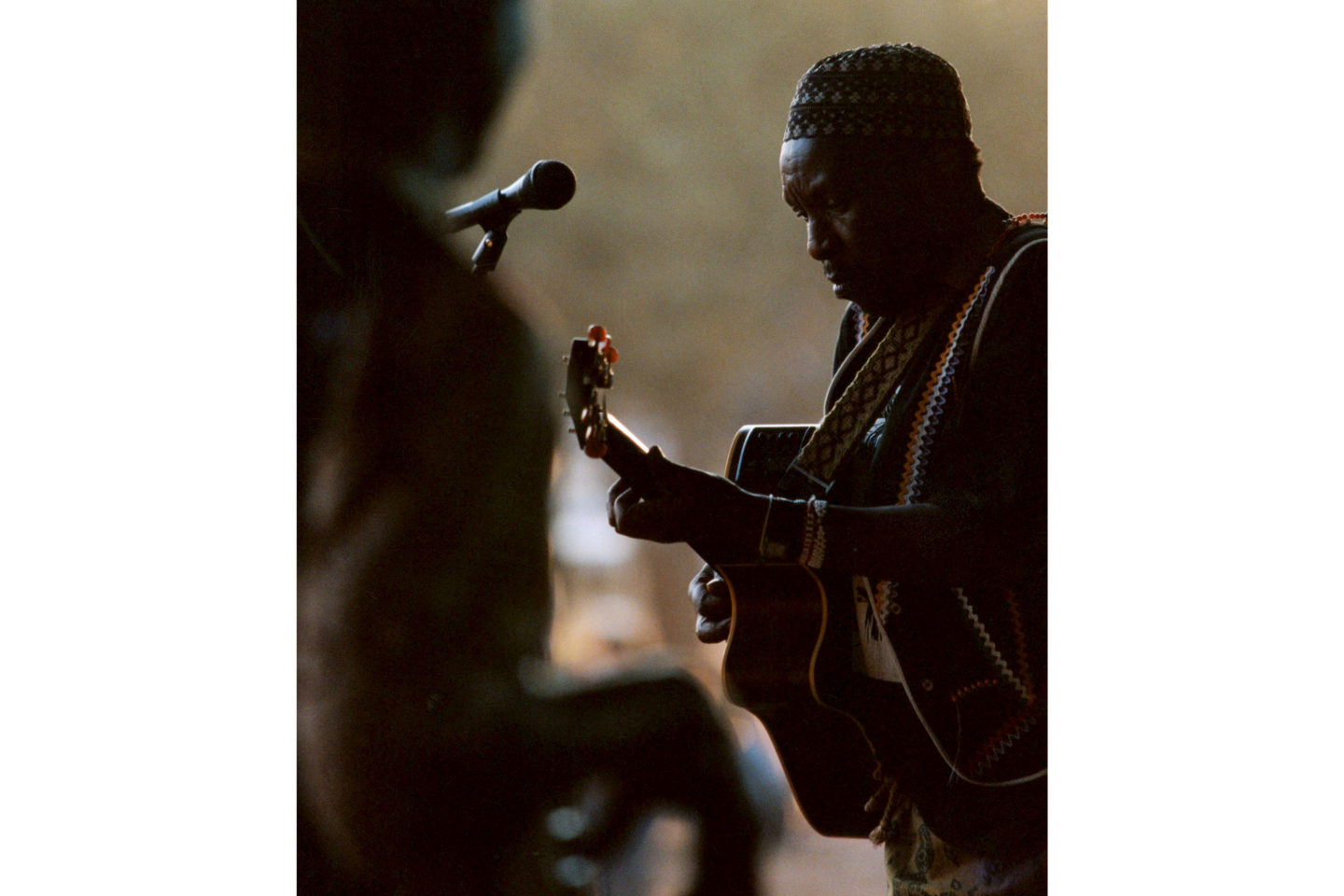

Madala Kunene tells his story through his guitars

The maestro’s music is tied to his lifelong connections to the places in the city where he was born and raised, learnt to play his beloved instruments and still makes a living.

Author:

19 October 2021

Cato Manor (Umkhumbane) in Durban still bears many reminders of the struggles over the future of this historic working-class shantytown. Everywhere there is palpable evidence of its violent history of dispossession, loss and resistance.

Musician Madala Kunene was born here, and his guitar is tuned to the structural features of its complex reality. The artist’s music is deeply embedded in a lyrical and honest excavation of the hardships of contemporary life, sometimes expressed through old idioms.

Kunene’s distinctive sound is probably more noted internationally than domestically. At his home in Hillary in Durban where he continues to compose, he explains that its uniqueness is rooted in the way he tunes his guitars, composing songs that express divination rhythms and draw on Zulu folk music.

During the interview, Kunene plays tunes from his storotoro (Jew’s harp) with comfortable ease, squinting his eyes into distant contemplation. Delivering an impressively peculiar tune, sometimes humming chants in between, he articulates speech-like sound with the harp.

Kunene then calls for his son to bring his guitars, each with its own name. He first picks up Fat Lady, his oldest and favourite guitar, followed by the other two, Little Lady and Lady Million. In an impromptu backyard show, his right foot taps and the connection with his guitar becomes a serious and mesmerising affair.

Kunene’s connection both to the instrument and a sense of the politics of place is clear. The elements in his music – its hue, tone, cry and joy – are the blueprints to his story, which is simultaneously the story of Umkhumbane.

Over the course of multiple conversations, Kunene shares stories, many of them relating a distant past when he had just started making music, while others involve his impressive collaborations with renowned artists and memories of happiness and success. But the story he tells of the present is one of unfulfillment and betrayal.

“The ambition I had devoted to creating music for social commentary will never fade. It is linked to my social call for humanity, for ubuntu. But I have spent too many of my years unrecognised by the people I do the music for: Africans. I have only received international acclaim, but never from my own people.

“After more than 40 years, I have decided to refocus on my future. In the end, I have a family, a house and no sound acknowledgement from the South African industry. Now, you speak to my manager, she is the only person who I can trust to help make sure I get well-paying gigs outside the country and that my children go to school,” explains Kunene. His words are punctuated by a sharp and uncomfortable pause – an impasse too hard to ignore.

Playing for pennies

In the beginning of his musical journey as a young child in Cato Manor, Kunene drew influence from his father and his brothers, who were amateur musicians in the neighbourhood during the 1940s and 1950s. His father Bantu Kunene often played his favourite songs on the gramophone and built Kunene his first guitar using a 5-litre oil can, a plank and three strings made of nylon wire. By the time the young musician was seven years old, he had mastered the home-made instrument.

He later started playing for money with some of his friends in the area. They called themselves “nikabheni” (give pennies) performers.

“The economic circumstances demanded even children to start earning as soon as they could in order to supplement the shortage of food and income at home,” explains Kunene. “This was normal. And so, nikabheni performances began.

Related article:

“My father performed in the backyard shebeens and public places in Umkhumbane. He would often play the guitar to make money from these spots. There was a friend of his, Ernest Khoza, who also played guitar, another man called Vonco Khumalo who would dance, and someone else known as Dixie. They were a group of friends performing together.

“We grew to love this as we watched them in awe,” he says. “It wasn’t long after [that] we decided to become the young ‘nikabheni’ performers, making pennies from the local spots and from suburban areas in the city.”

As he grew in age and musicianship, Kunene began playing a modified version of his homemade guitar – with the addition of an extra string. With four strings, he began imitating American influential jazz guitarist Kenny Burrell and British bands The Beatles and the Rolling Stones. In 1978, however, he took the decision to focus on creating his own sound.

Adding another string

Kunene’s is a storied life, which he relays with a richly textured narrative. He explains how he bought his first “real” guitar after playing at a jazz event at Curries Fountain in 1964, where he had met the late renowned drummer Mabi Thobejane.

“At that time I still didn’t have my own guitar, but I was almost good enough and we were making ‘pennies’ from our public performances. After enjoying the festival, I went backstage to meet some of the performers, and something about Thobejane struck me. And so I approached him and we instantly became friends.

“Making my way to the bus station with one rand in my pocket – just enough to get me bunny chow and a bus ride home – a man stopped me to sell me a guitar. He wanted 50 cents for it. I was keen. He took the entire rand and never returned my change. But I was ecstatic that I finally owned a guitar with five strings.”

For a short while, Kunene became part of Zanusi, the band that was established in 1988 by the late drummer Bruce Sosibo, a member of the Malopoets. Kunene sang lead, played acoustic guitar and the Jew’s harp. Zanusi was disbanded in 1991.

The 1990s was a time marked by his first individual releases. Kunene’s debut solo album, King of the Zulu Guitar Vol 1, a low-tech live recording, was released by the progressive record label Melt 2000 in 1995. The label, launched in 1994, released a large number of remarkable collaborative albums from iconic artists such as Kunene, Busi Mhlongo, Amampondo, Pops Mohamed, Vusi Khumalo and Bushmen of the Kalahari.

According to Melt 2000’s website, King of the Zulu Guitar Vol 1 is the work of the founder of the label, Robert Trunz, who says he recorded and filmed the unique encounter at the riverbank in the bottom of Kunene’s garden.

But it was Kon’ko Man, released in 1996, that would become Kunene’s most acclaimed album. “The recording was after meeting record producer Robert Trunz [through musicians] Airto Moreira and José Neto. I soon had the opportunity to record some of my songs on the album Isiqonqomane. But the name was later changed to Kon’ko Man. The release of the album effectively launched my international career, beginning tours in Tromso, Norway, and eventually touring the world,” Kunene says.

To understand what is profoundly distinctive about Kunene’s music – and has defined his success – one has to journey back to the place where he first picked up a tin guitar.

Space, sound and the state

Kunene’s music is inseparable from what poet Ronnie Govender calls “the spirit of Cato Manor” in his poem Who Am I, as Niren Tolsi recently wrote in his tribute to the writer. Like the wordsmith, Kunene’s life and artistry were informed by the space.

Culturally, Cato Manor is remarkably distinct. Kunene, along with Sosibo and the late Sipho Gumede, are among the musical luminaries born there during the early 1950s and part of a generation of cultural workers that also includes Govender and fellow writer Mandla Langa. Kunene’s work and politics were forged in the history of Umkhumbane.

In the anthology The People’s City – African Life in Twentieth-Century Durban (1996), co-editors Iain Edwards and Paul Maylam attempt to explain the origins of the apartheid city, investigating the development of urban racial segregation from the 19th century onwards.

This history is a story of urban regulation and control, and rebellion, ranging across the migrant labour and pass system, and the establishment and finance of locations, particularly the petty policies and revenue gathered from the monopoly of beer brewing and housing. Maylam writes: “The belief of Cato Manor inhabitants in their autonomy and independence was most strongly evident after the 1949 Durban riots.”

Related article:

Maylam also warns against “romanticising” the harsh realities in informal settlements, with poor living conditions and sanitation still existing in many of the areas. “Cato Manor not only symbolised the occupation of urban physical space, it also represented the opening of economic and political space. There existed many economic opportunities to supply basic commodities and services to the settlement’s rapidly growing population.

“These opportunities were exploited by petty entrepreneurs and by operators in the informal sector. Such activities took various forms. Some were conducted in an individualist style; others were organised on a co-operative basis. Most fell outside the realm of any legally defined, officially recognised form of enterprise,” writes Maylam.

The forced removals, under the apartheid Group Areas Act, and the destruction of Cato Manor by the state military and the municipality began in 1958 and continued for years.

Edwards writes: “In March 1958 the Durban corporation began the removal of Cato Manor’s inhabitants of KwaMashu. In June 1959 rioting broke out in Cato Manor. The resistance was initiated by women, particularly the liquor-brewers whose very livelihood was threatened by the destruction of Cato Manor. The women vented their anger by attacking the municipal beer hall in Cato Manor, overturning vats and destroying equipment.

Related article:

“For two weeks Cato Manor was the scene of overt resistance, expressed in demonstrations and clashes with police. And again, at the end of March in the following year in the immediate aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre, Cato Manor residents were once more at the forefront of resistance in Durban.”

Edwards’ work highlights issues of petty local state repression and gender militance as aspects in the Cato Manor riots, importantly revealing how women forcefully challenged both the state and patriarchs within their own community.

Today Cato Manor is “surviving” – the land was reoccupied in the 1980s, against the state, and a process of uneven formalisation began in the second half the 1980s. Today, occupations continue, and are once again met by serious state violence in a continuation of the vicissitudes of history.

History in the present

It is this history that is at the roots of Kunene’s album 1959, titled for the year of the beer hall riots. Released in 2015, he narrates Umkhumbane’s evolution across time, as a space that bears the mark of Africanist tradition and culture and sociopolitical struggles bulldozed by apartheid.

It is both a political and musical presentation of the destruction of the shack settlements of Umkhumbane, and the creation of KwaMashu, where many were resettled from 1958 to 1965, as a new model of modern urban society. Kunene tells the story of destruction and devastation in a chronological sequence. The songs Mlilo, Washa, Sphithiphithi and No Pass No Special talk of the ruins and the stiff resistance from its people.

Kunene’s approach was forged in a time when traditional Zulu music and South African jazz carried messages of resistance and colonial legacy. In his compositions, he employs material from Nguni oral performance traditions. He insists on this musical identity and is concerned that the lack of state support for South African musicians could “crumble” the sounds with historical and cultural importance.

His guitar technique distinctly flags a sound rooted in southern Africa. Some of his compositions are made up of imilolozelo (nursery rhymes), such as Khon’othwele and Igwababa from Kon’ko Man.

“Imilolozelo are songs everyone knows, passed down from generations. They have never been written down, but everyone resonates with them and enjoys them,” says Kunene.

A troubling reality

At the time of the interview, Kunene was working on a collaborative project with Thandiswa Mazwai. He continues to work with artists across the musical spectrum, fusing explorations with ground-breaking ensembles. Over time, his intergenerational collaborations have included the likes of Mhlongo, Mankunku Ngozi, Blaq Motion, Buhlebendalo Mda and Mazwai.

The musician continues to suffer from the financial devastation of Covid-19 and says he has been living from hand to mouth and survives with help from close friends. He misses travelling and performing on international stages and teaching music at an academy in Denmark.

“Covid-19 has hit us [musicians] hard, akusekho mnandi [things are no longer pleasant]. The pandemic exposed, in its realest form, the extent of the economic inequalities in this country,” says Kunene.

The arts and entertainment industries were among the first to close under lockdown in 2020, but Kunene says he has been financially suffering as he remains unsupported by the government. He is justifiably critical of the lack of support from the Department of Sports, Arts and Culture.

“It needs to go beyond the ‘my comrade’ model and serve its call to all its people,” he says.

Kunene also laments his lack of recognition and disregard from the public. “Gaining wealth and fame is based on pure luck in this industry. If it was based on true talent and meaningful content, I would be enjoying my legacy, with at least medical aid and a sense of security as a reward for the dedication, sacrifice and the constant battle to always remain original.

“Historically, African music has the ability to shape society. But who is there to listen to our music? There is no platform to enhance our music industry with its unique identity. There is only a drive for popular culture and bubblegum music. Even the biggest radio station that should be promoting South African music does not have even a single of mine on their playlist.”

His critique of the present is born from a concern about preserving the sounds of South Africa that have been forged in histories of struggle for generations to come. He also blames the custodians of our cultural industries for what he says is “a lack of cohesive local identity”.

“Historically, there had not been sufficient grooming of our talent for the music industry locally or globally, which had led to repercussions for the state of the current local industry. Now, kids hear a guitar from an old man and think ‘it’s maskandi, how boring’,” he says.