Mabandla’s 12-track generous exploration of love

Bongeziwe Mabandla’s new album explores a love story, from start to end, alongside parallel questions of memory.

Author:

3 April 2020

To watch Bongeziwe Mabandla step onto stage is to witness the transmutation of the abstract into the physical. The 32-year-old’s performances are probably best described as conjurings: a kind of magic that sees Mabandla act as an interlocutor between his listener and the wide range of emotion (loss, rebirth, love) that his music inspires.

Two Februarys ago, as the blue pulled away from the sky in Braamfontein, I made my way to the now-closed Orbit jazz club to see Mabandla perform for the first time. Having never seen Mabandla perform before, I had no idea what to expect. He was then known for his work as an actor – he played a character called Andy on Generations and had a recurring role on Tsha Tsha.

The night rolled toward the moon, mid-set there was a moment. Guitar in-tow, Mabandla paused to insert a preamble into his next song.

“I wrote this song a little while after living in Johannesburg,” he spoke into the mic. “It’s essentially about that feeling you get when you look back and think: how did I become the person I am? How did I lose so much of who I was?”

A few seconds later, the psalmist began his sermon:

Phambi kwabantu bonke ndiyafunga

Oba bomi bendibuphila

ndibushiya emva

Lemini sisiphawulo

Iyandazisa

At its core, the lyrics are a prayer bound by the contours of return. Mabandla makes a solemn declaration “in front of every living being” to cast his current self in the future and no longer be the person he used to be.

He laughs when reminded of the memory. “Yeah, I always try to make my music as biographical as possible. Mangaliso was an album about spirituality. I wrote it during a period of rediscovery, when I wanted to reconnect with who I was before I moved to Johannesburg. But my new album is about something else entirely,” he says.

A dimensional approach to a love story

Mabandla’s latest album, iminii, is a 12-track exploration of love, its animating power, limitations and its inevitable end. Initially recorded over 21 days in March 2019, and refined over the months that followed, the Tsolo-born artist maps out the lifeline of a relationship over folksy guitar riffs, pulsing synth lines and restrained percussion.

It’s a devastating listen, especially given how beautifully the album-opener, mini esadibana ngayo, sets us to believe that this might be another one of those love-inspired albums. You know the kind? Boy meets girl, serenades her with his guitar, before they lock lips in slow motion over a field of slow-moving daisies.

It’s a beautiful story, if you can live it.

“I wanted something that went beyond that. The album’s inspired by a series of events that happened in my life,” he says without giving any more detail. “I was more concerned with trying to figure out how it is that someone who used to be in your life – someone you imagined yourself growing old with – falls out of love with you? Where does that person disappear to? The album is about the days we spent together and looking back for both the memories and answers.”

Organic experiment in rhythm and melody

When Mabandla released his debut, Umlilo, in 2012, a certain musical description was tethered onto him: Afro-folk. It is a label he did not mind, but he is the first to admit his music bares little resemblance to his debut. His musical pairing with 340ml’s Tiago Correia Paulo on Mangaliso continues here with its experimentation of electronic rhythms sitting underneath his guitar melodies.

On masiziyekelele (14.11.16), he describes the dizzying pull of young love. “Akekho umuntu omhle nje ngawe,” he sings, inviting his soon-to-be-lover into his heart with hyperbolic expressions of their beauty. A chorus of synth-blips, a rubbery bassline and, finally a marching drumline, enter the fray before Mabandla tells his lover to let themselves go and swing along with the tide.

A few songs later, Ndanele (which loosely translates to “I am whole”) opens with a haunting hum that stands opposite to the song’s theme. Mabandla repeats the song title, almost as a seance before delivering the kicker: ‘uthando lwakho lungandenza ndonele’ – it’s a sentiment widely shared in most love songs – the power of romantic love making the receiver “whole”. But alongside Mabandla’s guitar riffs and pensive lyrics, it never devolves into oversentimentality.

“I don’t think there was an intentional effort to make the album experimental: that’s just a result of working with Tiago. I wasn’t going out of my way to make the album sound like Mangaliso because I don’t think it does in many respects. But it’s also true that, when I wrote Mangaliso, I wrote most of it before I knew he was going to produce it. This was different because our previous work together was an anchor but all of it was organic.”

A devastating turn

As the album’s narrative continues to play out, a message begins to cohere: the centre will not hold. On, ukwahlukana, a cry pierces into the black echo and then, amongst the soft tapping of a glockenspiel and piano chords Mabandla begins to ask: What went wrong? “Ndakunika elinye ithuba, wakhetha ukuphinda undikhathaze,” he says, expressing his patience with the unfurling relationship running thin. Son Little (the only vocal collaborator) chimes in with a few lines about never feeling good enough for his romantic partner.

What follows next is, without doubt, the album’s most devastating moment. bambela kum, is a gentle-guitar ballad that starts with the question: “kutheni siphathana kanjena?” His words half-insisting that they could still treat each other as tenderly as they used to. Mabandla pleads with his partner to “hold on” to him. The song is a plea for togetherness even in hard times. But there’s nothing romantic about the request. It is a desperate plea: the kind you make when you can see the end coming into sharp focus.

The renderings of memory

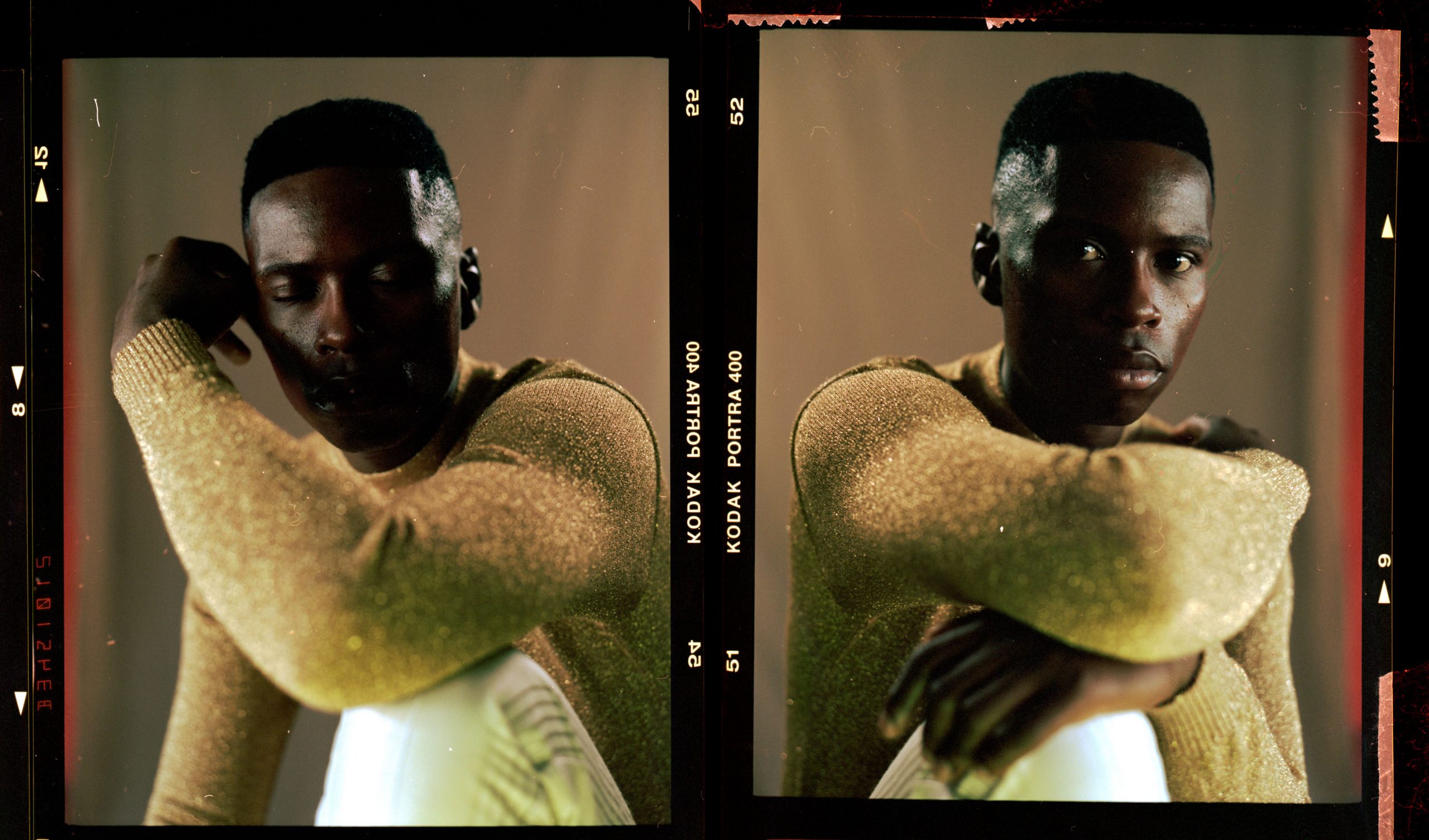

If an album cover prefaces what to expect on an album, now might be a good time to consider iimini’s. Half-drenched in darkness and light, Mabandla’s body is tilted slightly toward the camera. A naked moment suspended in time, the picture seems to suggest he’s turning to something. A deliberate misreading might suggest he’s in the process of turning away from it. Rendered in 120mm film, the image by Lidudumalingani Mqombothi produces a kind of faux-nostalgia that suggests the moment could have been captured years before the modern architecture in the background suggests. A false memory, stuck in between the present and some distant past.

The picture is representative of the album’s secondary theme: memory. For the most part, memory is in service of the narrator. The mind does its best to keep dissonance at bay, so most memories are reconstructed to the point of myth: nothing was ever the narrator’s fault.

But in his renderings of memory, Mabandla does away with the need to lay the blame at the feet of his past lover. In fact, ndiyakuthanda – the album closer – sees him make a decision uncharacteristic of most breakups: to love what remains. Left with nothing but the memory of his former lover, Mabandla immortalizes the memory of his relationship with a promise “andikwazi ukuyeka ukukuthanda”, vowing to keep loving her in spite of his loss.

Love is many things. But more than anything, to quote Charles Bukowski, the “poet laureate of American lowlife”, love is a dog from hell.

“Love is kind of like when you see a fog in the morning, when you wake up before the sun comes out. It’s just a little while, and then it burns away… Love is a fog that burns with the first daylight of reality,” said Bukowski in an uncharacteristic moment of lucidity.

Mabandla wrestles with its nature throughout iimini, eventually resigning himself to the fact that you cannot change the past, but you can choose how to carry what it leaves in its wake.