Long read | Workers as artists, artists as workers

Inclusive creativity has the power to remake the world – it is potentially revolutionary, but only if artistic production is wrested away from capitalist exploitation.

Author:

30 September 2021

This is a lightly edited version of the keynote address at the inaugural event, on 24 September, of the Political Revival programme at The Forge.

Comrades and friends, greetings on this Heritage Day weekend. I’m honoured to have been invited to this very first political revival event.

We all know what the official events to mark this holiday look like. A government representative stands up, names a South African writer, painter or musician of the past, and delivers a sketchy life story and some lavish praises scripted by one of their civil servants. Occasionally, the speech adds how tragic and shocking it is that the artist in question had to die in poverty. A statue or exhibition may be unveiled. Maybe there’s a tickets-only banquet with a “cultural performance” to entertain while people drink and eat lavishly (the performers often get a few sandwiches elsewhere). The speaker tells us to be proud of all this wonderful cultural heritage. Then it’s all shut away again to gather dust until next 24 September.

Those aren’t our politics; and that’s absolutely not what we mean by arts, culture and heritage.

Culture isn’t just performance or attire, it’s all the dynamic patterns of how we live and live together. Heritage isn’t just statues or exhibitions but everything, including language and memories, handed down by earlier generations that we choose to retain. So for working people, whether formally or self employed, collective struggle is integral to both our culture and our heritage. And the arts – far from being something just to be consumed – are our voices to recall, express and if necessary reshape this culture and heritage.

There’s a famous headline from the Freedom Charter: “The doors of learning and culture shall be opened.” It’s about free education, sure, and free access to cultural resources. But it’s about more than that. Most significantly, the first clause of that section reads: “The government shall discover, develop and encourage national talent for the enhancement of our cultural life.” (Not to sell to tourists – to enhance our own cultural life.) In other words, it asserts the right of working people to be artists and be supported in their cultural work.

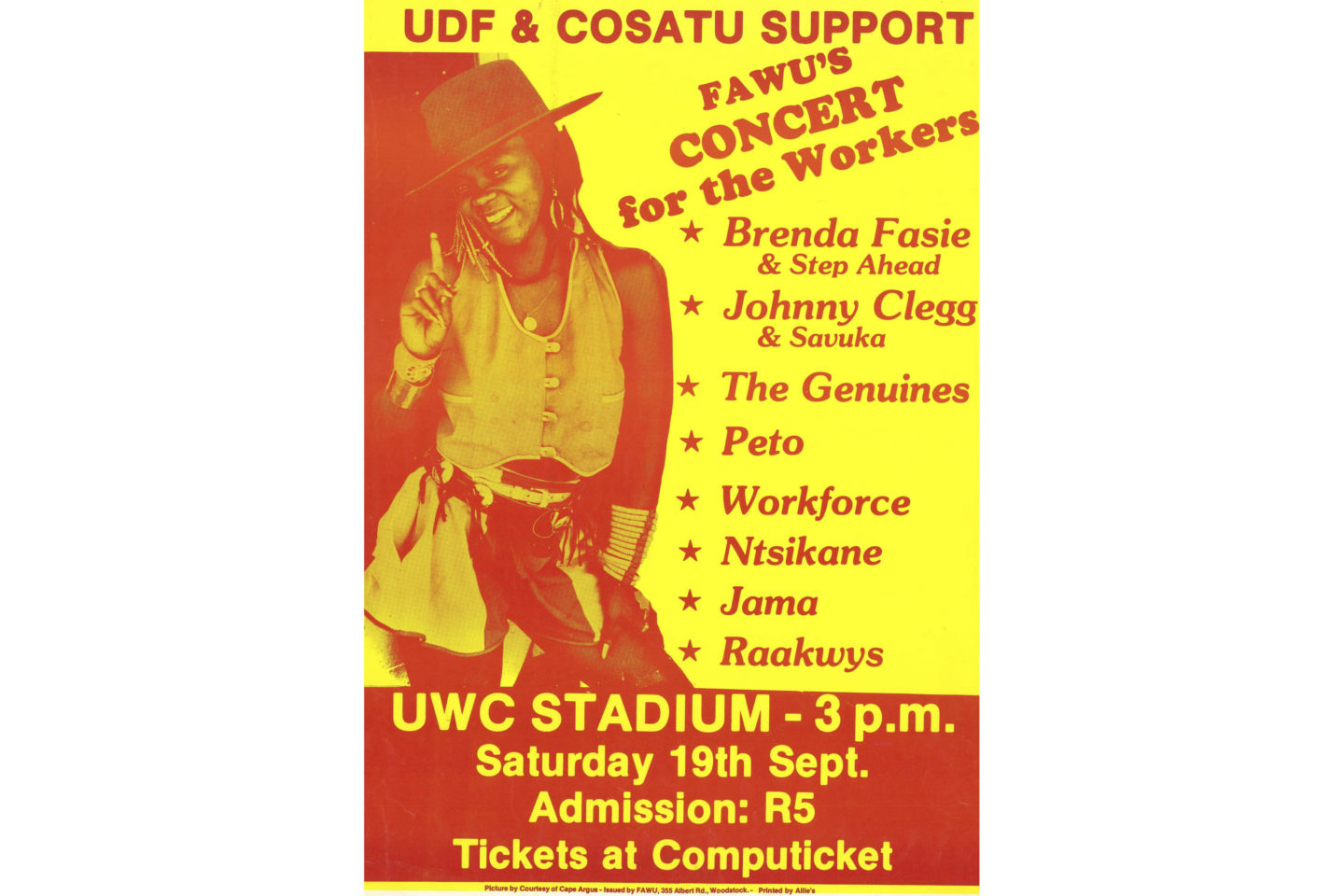

At the height of the struggle during the 1970s and early 1980s, you could open a copy of the progressive arts magazine Staffrider, and find at the back a list of dozens of active cultural groups – in communities, in factories, attached to trade unions as “cultural locals” and more. Townships reclaimed space for People’s Parks: places to meet and breathe long before “greening” got fashionable. Organised workers, innovating from creative practices in their communities and from the pan-African and international examples of resistance culture, shaped their own visual language through posters and banners, wrote and performed poetry, created plays such as The Long March. They added a new genre, mzabalazo, to choral music, fresh in subject matter, costume and gesture. The Braitex Choir sang, “Come together workers and be one so we can defeat the bosses with our numbers.” That’s the heritage that the Abahlali Women’s Choir we’ll hear today are carrying forward.

People in struggle discovered their creativity and saw they could own and liberate it to remake their world. A vital part of that was their process – collaboration in creative collectives born in and nurtured by their communities: what revolutionary Medu artist Thami Mnyele in 1982 called the connection to “the river of life”.

A shift in culture

That rich community culture didn’t last. Cosatu established a cultural desk in 1985, the year of its birth. But murderous attacks from the regime at home, massive organisational burdens and increasingly centralised approaches to culture from the exiled ANC Department of Arts and Culture abroad all combined to make grassroots cultural organising harder. Four years later, Albie Sachs proposed that we inaugurate a new democratic culture by banning the phrase “culture as a weapon of struggle”. Compromises emerged and priorities changed. By the early 1990s, we were seeing the first signs of the official view that flourishes today: the arts as something people buy, not something people make, and as a servant of official policies. As poet Ari Sitas described it, in the first democratic government “culture was handed to Inkatha and creativity to the market”.

We’re very far, these days, from opening the doors of culture to all people as both audiences and makers. Tickets are expensive; many heritage sites have to charge entry fees to survive. As spending on education is trimmed to save money, arts teaching in the schools of the most impoverished communities has almost disappeared. Even in better-resourced schools, parents often have to pay extra and the artists who teach work in insecure conditions, sometimes on near-volunteer stipends. Adults with low or no income seeking to become cultural makers will find even less.

Grassroots cultural initiatives do survive. Today we hear the Abahlali Women’s Choir and we may also think of the Moses Molelekwa Arts Foundation in Tembisa and the Feminist Women’s Art Network collective. There are many more. But they struggled for resources even before Covid devastated the creative landscape. Those struggles and that devastation, I’ll come back to later.

Treating culture as just another capitalist industry ignores – or more likely deliberately stifles – the fact that everywhere working people gather to paint, or sing, or play an instrument, or write a poem, a life story or a rap lyric, the most tremendous power is unleashed. Making art together – like doing anything collectively – brings people together to enact a different kind of democracy they can bring to other areas of their lives. Swedish worker-poet Jenny Wrangborg – who worked in a restaurant kitchen – said that “by writing about what was close – the time clock, the boss and colleagues – I also discovered everything else: the system, exhaustion, solidarity and opportunities for change”.

Making art together runs on a politics of respect and acceptance. It links us as people and communities. Discovering you can create a striking image, or a catchy tune, or powerful words, frees the confidence to assert our own experiences and feelings. It helps rebuild hope when that has been systematically dismissed and undermined by the system.

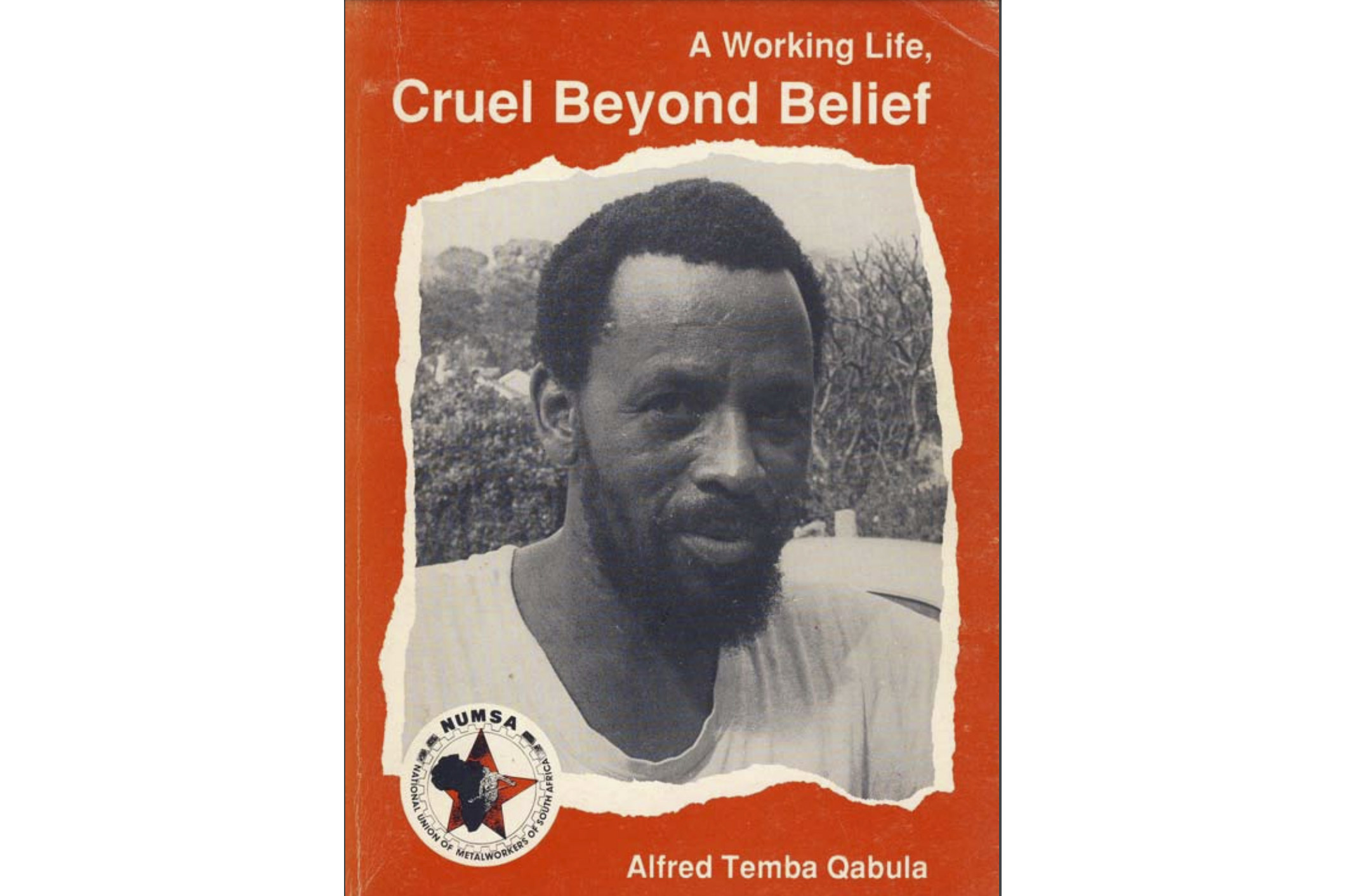

Listen to worker-poet Alfred Themba Qabula: “The powerful ask / Who allowed these stalks of cane, these blades of grass, to sing? / Songs are the property of trees, you have to be tall / you have to have substance, stature and trunk to sing / But we sing.” (In The Tracks of Our Train)

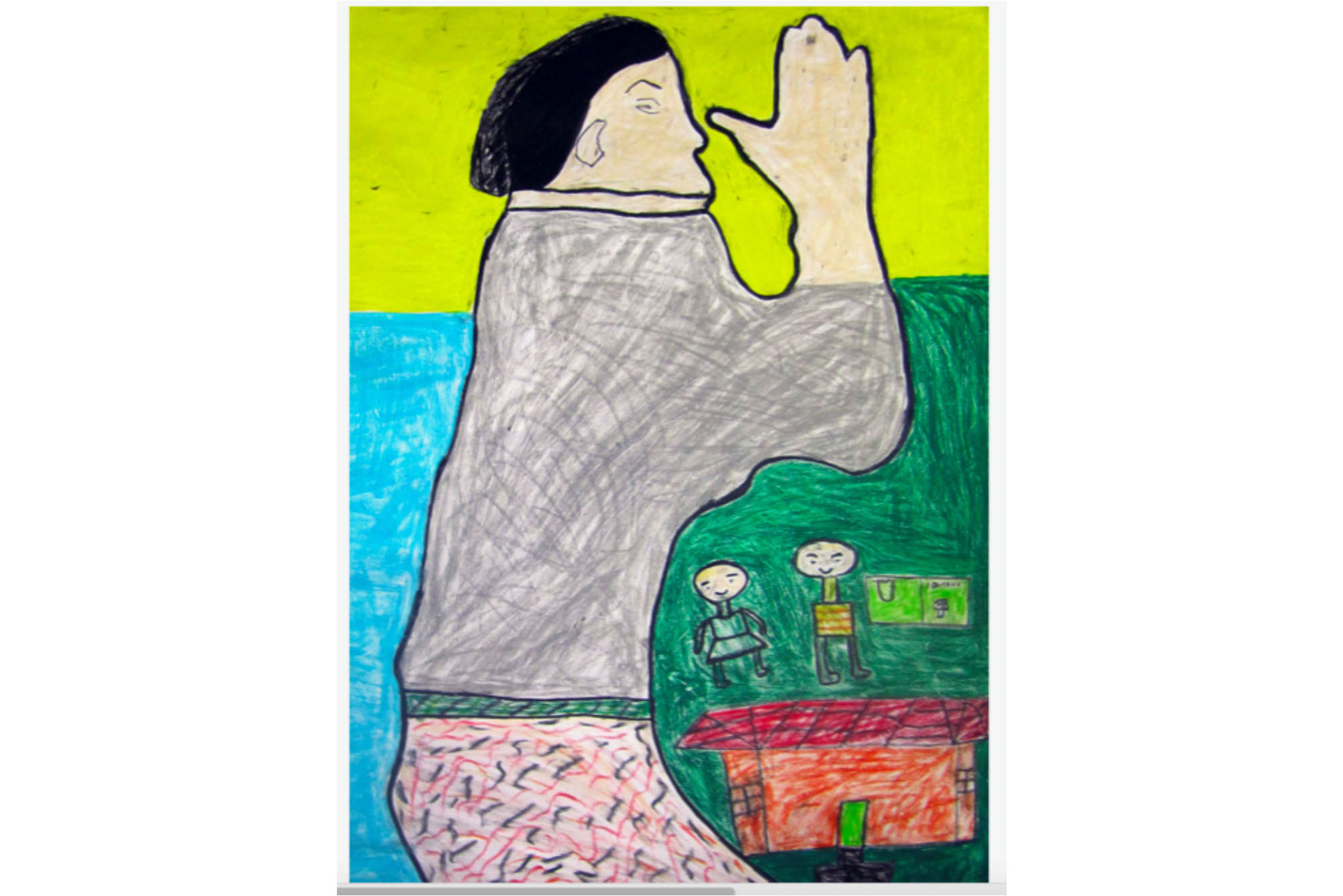

Listen to Mathabang Ntsenyeho, the widow of one of the miners murdered at Marikana, talking about a painting she made in a 2013 collective art-making workshop about the event. Her choices about what to show and how to show it to convey her experience, her images, colours and symbolism, are all deliberate and considered. She speaks not as a “victim” but as an artist: “My name is Mathabang Ntsenyeho. I am coming from the Free State in the area of Sasolburg. After I received the news that my husband had passed away, I am sitting and praying: why did this happen to me? These are my children. That is the house, our dream house, which we had hoped to build with my husband. There is my ID – as you see me I am coming from Lesotho, I do not have an ID. The yellow colour there shows the peace and happiness when I was living with my husband. The blue colour shows the tears that have been falling from me and my children; the pain I have when I think about the police who killed my husband. I am feeling the pain. That green colour on the other side is the pain in my side, which is hard to live with.” (Translated)

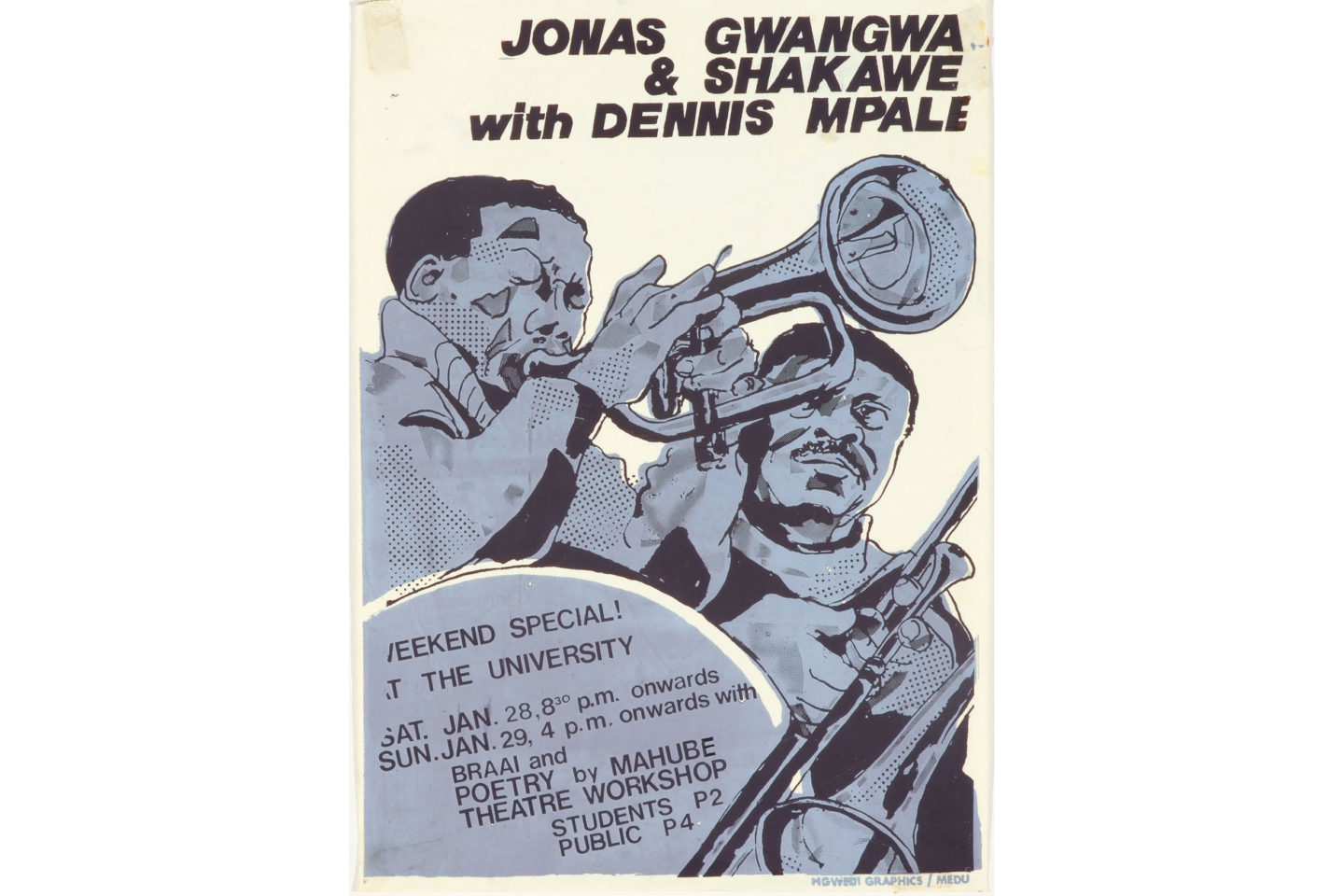

Some very beautiful work, with a distinctive aesthetic has emerged from art explicitly asserting messages of struggle: the poetry of Qabula, Ingoapele Madingoane, Keorapetse Kgositsile, Don Mattera and Frank Meintjies whom we’ll hear later; the music of Jonas Gwangwa; the visual art of Thami Mnyele or of Malangatana Ngwenya in Mozambique are only a few examples.

Nurturing liberating spaces

But making art can do these things even when it doesn’t explicitly contain a slogan. An old song sung by women workers says that people need both “bread and roses”. Just declaring your identity and experience, or calling up beauty against harsh capitalism can itself be revolutionary. “Trying to make beautiful music in an ugly society” was one of the things struggle musician, jazz trumpeter Dennis Mpale said he was doing – he saw that, in parallel with his underground military activities, as essential to his mission.

So one key element of rebuilding has to be nurturing liberated local spaces where working people don’t have to travel far to make art and master the skills of telling their own stories, and to hear and understand the stories of the others who live, work and march with them.

But that takes resources. And that brings me to the second part of this topic: the working lives of artists. The two are interrelated, because those who have already mastered creative skills are the ones who can collaborate and teach, as I know Yonela (who’ll be performing later) does with young singers. To do that kind of thing, artists need to survive.

Instead of cultural production done together, in communities, our society entrenches the divisions of capitalist industry in cultural production. It divides makers from consumers. It takes away from the people’s creators and innovators the channels to spread their messages. The wealth produced by cultural workers goes to bosses and so-called “cultural entrepreneurs”. In 1988, playwright Matsemela Manaka pointed out that art, like the land, must belong to those who work on it. We seem to have forgotten that principle.

Unlike some official spokespeople, I’m not at all surprised that so many artists die in poverty. The majority of South Africans die in poverty or something very close and our artists are the sons and daughters of the people. But the devastation that Covid and the government’s wilful ignorance and neglect have created among cultural workers is making a tough situation far worse.

There was no live performance work for most of last year. In the music sector alone, a 2020 survey showed that nearly half our musicians were considering quitting because they couldn’t survive. They were selling off instruments to pay bills – just pass your local Cash Converters and look at how many instruments and amplifiers you see; each one represents a musician who needs to feed her kids or pay school fees. Without instruments, they can’t practice, get de-skilled, can’t accept some jobs that require them to supply their own equipment. What’s more – because prices have gone up, and they’re still catching up on debt – they may never, ever be able to replace what they’ve sold.

Live performances are back (until the next Covid spike) but by now many venues and services such as sound engineering have closed for good. Musicians selling their music online through a streaming service such as iTunes must pay to use that service (usually in dollars). They earn 0.000-something cents or less per sale. Do the sums the next time you buy a track online, and think how little goes to the musician.

Artists often work by coming together in different combinations for short-term projects: a play, a film, a recording, a festival. There can be long gaps in between. The structures of the capitalist arts industry (and government policy) mean even well-known artists have to stretch their earnings across those gaps. They haven’t stopped working, because they still need to write, compose, practise or paint. Unlike in a socialist country such as Cuba, there’s no support for that or for any of the costs it involves.

That’s already tough – but some bosses turn it into the most extreme form of enforced labour precarity. If you’re an actor on a TV soapie, for example, which looks like a nice steady job, you’re very likely employed “on call”. That’s essentially a zero-hours contract: you can’t risk taking other work because you’ve committed to being instantly available. South African production companies pay the lowest call fees in the world, and some pay nothing at all.

Toward new formulations

In the struggle period, artists’ unions campaigned and confronted the system. Today we see many professional pressure groups of creatives, but nothing that quite does what a union does: taking on exploitative bosses. Instead, we have CCIFSA (the Creative and Cultural Industries Federation of SA – the very name buys into the commodifying discourse of global capital). We don’t know how many members it has. Its current leaders may be well-intentioned – I don’t know, and don’t want to speculate – but it was born under the patronage of the Department of Sport, Arts and Culture (DSAC), which had given it R13 million up to 2019. DSAC is also a sector employer. That raises very uncomfortable questions for those of us who know the term “sweetheart union”.

Another key element of rebuilding, then, might be for people’s organisations to build links with artists as exploited workers, creating formations that can articulate economic demands in the context of culture as an expression of resistance and change.

As well as standing shoulder to shoulder with cultural workers in those kinds of struggles, there are many other demands worth considering. We could start with the rest of what’s in the Freedom Charter, including genuinely free education as opposed to “free but you have to pay for transport, uniforms, books – and of course art and music classes”.

A campaign against the hegemony of the FAANGS (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, Google and Spotify) could highlight how these companies impose the values of capitalist globalisation on South Africa and exploit South African creators.

A demand to bridge the digital divide, with lower data costs and more access, would put both creators and audiences in a better position to develop homegrown platforms and modes of economic survival that challenge the global platforms.

A demand that social grants should include a cultural voucher to spend on a performance, artwork, recording or book – which every citizen received in Lula’s socialist Brazil – could help rebuild audiences and support for cultural workers.

Campaigns around who gets to teach arts skills at every level (and what they are paid) might break down some barriers for potential teachers and learners. Why are so many musicians unemployed when so few state schools have a music teacher?

Related article:

Intelligently implemented local content quotas for broadcasting can create work and revenue for artists. Those quotas shouldn’t be so high that they cut us off from the rest of the world – I’m not talking 90% but perhaps Icasa’s proposed 70%. Elsewhere in the world, for example Australia, local content quotas helped to support artists and others in film production and music. But they won’t work at all unless there is actual payout of what is due to creators.

None of these demands is in itself revolutionary. Much other work on many other fronts – organising, campaigning, occupying, resisting – is needed as well. But winning some of them could help create the space needed to restore worker culture. And, as the late cultural scholar Bheki Peterson, taken from us by Covid earlier this year, said: “restoring worker culture is a key act of decolonisation”.

Viva our collective heritage of struggle! Viva the power of workers as artists and artists as workers, viva!