Long Read | Wamba, militant African intellectual and friend

Ernest Wamba dia Wamba loved to laugh. He combined a lifelong commitment to emancipatory politics with a deep-seated African humanism.

Author:

23 July 2020

On 15 July, in Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ernest Wamba dia Wamba Bazunini left this world. No doubt the usual clichés will abound. A “great son of Africa”, “an intellectual giant”, “a great pan-Africanist” and so on as people revert to the tired old slogans they regurgitate every time an important intellectual figure joins the world of the ancestors.

Wamba would have giggled at this, as was his wont. He was keenly aware that behind such empty slogans are precisely empty politics, and that these slogans are a substitute for what he saw – and deplored – as the absence of political thought among many intellectuals in contemporary Africa.

Wamba (as he was known by all) was a rare phenomenon. He was an organic intellectual in the full sense of the term, and one of the greatest on our continent. He lived his life in complete fidelity to his political principles and at considerable personal cost, having endured arrest and detention, been a protagonist in armed struggle and narrowly escaped assassination attempts on several occasions. His principles were founded on drawing all the consequences from the axiom that it is the people and the people alone who are the makers of the emancipatory currents in world history.

I had the singular honour of interviewing him over five consecutive days in May 2019, during which our conversations covered all aspects of his politics and his philosophical thought. In fact, the two were practically indistinguishable.

Wamba was totally at ease discussing the state in ancient Egypt, the Mobutu regime, the problems of the nationalist movement in the DRC, the intellectual debates at the University of Dar-es-Salaam in the 1970s, African spirituality, pan-Africanism, the politics of the Cultural Revolution in China, the philosophies of Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Alain Badiou, the neocolonial character of liberal democracy in Africa, the dominance of statist conceptions of politics among ordinary people in the DRC or the sound of the guitar played by Franco, the King of Rumba.

Collective community meetings

Wamba was born on 16 April 1942 in central DRC in a Kikongo-speaking area. His was a peasant family and he was deeply immersed in local traditions from his early youth. He learnt respect and love for humanity from a young age, with his values centrally concerned with treating people with dignity and respect. In Bakongo communities, the importance of resolving non-antagonistic contradictions in a manner that was participatory and democratic was absolutely fundamental to holding people together.

It was out of the experience of attending a number of these collective sessions, in the form of a mbongi or palaver – a community method and practice to resolve contradictions among the people – that he wrote what is probably his most well-known work, Experiences of Democracy in Africa: Reflections on Practices of Communalist Palaver as a Method of Resolving Contradictions. His study of the palaver was not anthropological. In this study, and throughout his work, he related popular practices and struggles to a politics of emancipation that he was constantly rethinking and developing.

Related article:

The central concern of politics for Wamba was not war or violent antagonism, but the production of a collective unity. He insisted on the fact that his politics were always directed to bringing peace to the DRC (as it happens, the name Wamba means the one who brings peace). In his view, the failure of the state in post-independence Africa was precisely the failure to develop a shared understanding of an idea of the “common good”.

There are perhaps two dominant themes running through his intellectual and political work. One, the importance for the state in Africa to understand the need to manage the “common good” rather than the interests of (neo)colonialism, and historically its total inability to do so, a fact that implied its failure to adhere to basic universal democratic norms. Two, the unavoidable centrality of independent popular organisations in emancipatory politics to a) hold those in state power to account and thus insist on genuine, popularly founded democracy and b) provide the basis for popular movements to defend those who end up in power and attempt to oppose (neo)colonialism.

In Wamba’s view, without popular democratic organisation, pan-Africanism was impossible and Africa would be doomed to continue as a neocolonial amalgamation of countries ruled by predatory and repressive elites with disastrous consequences for its people. Of course, this never meant the abandonment of an idea of class struggle but rather an insistence on the idea that to effectively engage in political struggles, the unity of the oppressed is an absolute necessity.

The state as an external imposition in Africa

For Wamba the primary failure of most African intellectuals is a virulent and obvious state fetishism with a consequent inability to theorise politics as being conditional on emancipatory subjectivities to be founded on the politics of the organised masses, much as was the case with Amilcar Cabral’s famous prescription to Return to the Source. Without a popular mass movement, there could be no emancipatory politics.

The problem of the state in Africa was not so much the absence of institutions but that existing institutions were modelled on the West, so that the state – even after independence – remained an external imposition disconnected from the people it was meant to govern. In his well-known expression, the postcolonial state was simply “grafted” on to the pre-existing colonial one, thereby making it impossible to transform Africa along a popular-nationalist conception of genuine emancipation.

Wamba argued that Africa in general, and the DRC in particular, remained the prisoner of a predatory capitalism that systematically engaged in the mass torture of a continent. The result was that, following the colonial “civilising mission”, Africa experienced a Western “developmental mission” soon followed by a “democratising mission” in which a travesty of development and democracy were deployed and more frequently imposed. African leaders were, in the main, unwilling to work to support the realisation of the needs of the continent’s people because they allowed their interests to coincide with those of the West. Much like those traditional leaders and kings who had sold their people into slavery, postcolonial African leaders continued to sell their people to Western interests while blaming the latter for the people’s poverty.

Related article:

Wamba stressed that Africans should undertake a study of their own past, including of their popular struggles and similar ones such as those of the Chinese, to elucidate theoretical signs and alternative political conceptions. This requires self-criticism and a thorough spiritual cleansing. Such study could learn much, for example, from the idea of Ma’at in ancient Egypt, which insisted on the maintenance of social balance and an ethical life that venerates justice and truth. The point here being that, even in the conditions of the existence of the pharaonic state, in other words of extreme power differentials, the interests of minorities excluded from power would be taken care of to a certain degree. In this way, at least some sort of social balance could be maintained and chaos, the main fear of the ancient Egyptians, avoided. Of course, this didn’t always happen in practice.

Wamba also invested considerable intellectual energies to an elucidation and examination of the historical predictions and prescriptions of anti-colonial millenarian movements. One of these was the movement led by Simon Kimbangu in the DRC of the 1920s, for example. He predicted the subservience and corruption of post-independence leaders to Western dominance and insisted on the need to fight the destruction of African languages.

For Wamba, these movements sometimes expressed political prescriptions that were politically more important than those of many Western-trained academics. He said that one had to learn from these histories and, in general, the emancipatory prescriptions emerging from popular ruptures with the order of domination.

The philosophical result of these reflections was Wamba’s insistence on knowledge acquisition as a collective as opposed to an individual activity, and on dialectical thought, namely the recognition of contradictions and divisions along with their trajectories, as being at the centre of emancipatory political thinking. These philosophical views dovetailed completely with Wamba’s personal lifestyle and political commitments.

At a personal level, Wamba was an extremely spiritual person and would not see his departure from the living as in any way an end point. Rather, the idea that a person’s soul (or whatever one wishes to call it) could be resurrected in someone else was an African belief to which he held strongly. He was fully immersed in ancestral reverence and communication. The coercive separation of Africans from their spirituality was, for him, one of the more nefarious aspects of colonial domination.

Political involvement from a young age

Wamba’s political involvement began at the age of 14, when he was elected president of the teachers’ union while teaching French to nurses at a medical school. He was also the secretary and then president of the school debating club. His political practice took off from there.

He was offered a scholarship to the United States, where he became part of what was called the Black Action Movement at Western Michigan University. He met civil rights organiser Stokely Carmichael and received the Robert Friedman Philosophy Prize for his masters dissertation.

After returning home, Wamba entered government as the personal assistant and eventually principal secretary to the minister of social development and housing. He had the opportunity to go to France, where he met and became involved politically with other philosophers such as Badiou and Sylvain Lazarus.

Back in the US, he was again involved in student politics, teaching a course on the political economy of the Third World at Brandeis, Harvard and Boston College. He took part in creating the Student and Workers for African Liberation committee, with which he worked politically from 1973 to 1978.

Wamba then left for Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, where he took up a position in the history department of the University of Dar es Salaam. Here, he ran the history seminars that became a major centre for intellectual debates. This is where I first met him, in 1982. By then, Guyanese historian Walter Rodney had left and Wamba became critical of both positions taken in the so-called Dar-es-Salaam Debate, saying that rather than discussing capitalism or socialism, the primary focus should be on neocolonialism, which had to be thought in itself as a new historical epoch.

A reluctant leader of a rebellion

In December 1982, Wamba was arrested in Zaire (the DRC today) while travelling through Kinshasa. He was caught with a paper he was writing that was critical of Mobutu’s idea of “authenticité”, which was the dictator’s idea of African nationalism. For Wamba, this was simply a neocolonial notion. As a result of international pressure in the US, France, Britain and Tanzania, and the personal intervention of Tanzania’s first president, Julius Nyerere, he was eventually released in December 1983.

He later became a member of the National Sovereign Conference (1991-1992), which was a genuine attempt by the Congolese to establish a new form of state as Mobutu’s power waned. Mobutu managed to frustrate the conference’s work with the backing of the US.

Related article:

From 1992 to 1995, Wamba was the president of The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (Codesria), which is headquartered in Dakar, Senegal. After ending his term as president of Codesria, Nyerere sought out Wamba’s advice with regards to the DRC.

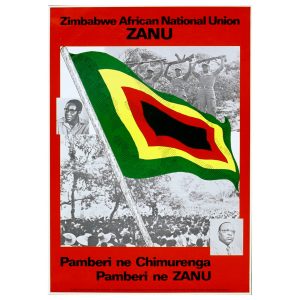

Congolese revolutionary and politician Laurent Desiré Kabila had been in exile in Tanzania, but on invading the DRC with the support of Rwanda and Uganda, Nyerere feared that massacres may take place in Kinshasa. After achieving power, Kabila started persecuting ethnic minorities with the result that an alliance of opposition parties, the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD), was formed. This alliance of various disaffected groups, ranging from ex-Mobutists to ethnic Tutsis and Left democrats and radicals, was in search of a presidential figure acceptable to all. In 1988, Wamba was reluctantly persuaded to take up this position, which he deemed inevitably necessary as a contribution to liberating his people from centralised state oppression.

Armed struggle and academic controversy

Nyerere was a particularly important figure in Wamba’s political life, because it was he who persuaded him to lead the RCD rebellion against Kabila. Nyerere was able to provide him with support so that the interventions of Rwanda and Uganda within the coalition were restricted. With the death of Nyerere in 1999, that support evaporated and the RCD broke into an ethnic faction based in Goma and a democratic faction led by Wamba, which moved to Kisangani.

Although involved in an armed struggle, Wamba was insistent throughout that attempts be made to encourage the development of a popular democratic movement in that part of eastern DRC to combat militarism within the state and the opposition. For Wamba, military power was always to be subordinated to popular democratic power. His attempts to build a movement in the context of war were largely stillborn. The rest, as they say, is history.

Related article:

Wamba’s participation in this struggle was the subject of often vociferous controversy among African scholars in Codesria. Unlike many of his colleagues who insisted on the separation between academic work and politics, while being linked to states and non-governmental organisations, Wamba was a movement intellectual who held that intellectuals should be practically committed to Africa’s liberation. He was vilified by many of his erstwhile colleagues for being “subjective”. By committing himself to a struggle he had, in their eyes, crossed a line. Some even accused him of recruiting child soldiers. This was a pure fabrication, of course, but what upset him most was that few of his African academic friends ever took the trouble to go and see him, to listen to his point of view and engage with him.

This was the case even when he was in South Africa and Botswana while the negotiations were taking place. Apart from Zimbabwean Ibbo Mandaza, who wanted to listen to his side of the story, he was almost universally condemned for “mixing politics with academics”. Of course, the liberal notion that academic discourse was apolitical and that state democracy allowed for independent thinking was making a comeback at the time.

After the peace negotiations at Sun City in South Africa, the war ended in 2003 and Kabila’s son Joseph assumed power and was recognised by states around the world. As part of the compromise, Wamba took a position in the Senate, where he was a prominent advocate for the subordination of the neocolonial state to popular democratic practices. However, the new government swiftly collapsed into complicity with neocolonialism and a predatory relation to society.

Last years of struggle

In his last years, Wamba was engaged in developing political discussion groups (he called them mbongi a nsi) in Kinshasa and engaging in pan-African activities while in Dar es Salaam. He sustained warm relations with activists, movements and radical intellectuals around the continent, including in South Africa, where he was seen as an elder by social movement and trade union activists.

Wamba’s intellectual work, although published in scattered places, is being brought together by friends. Although he was a complete human being who will be sorely missed by many of us, his spirit and work will live among all oppressed people, particularly among those Africans seeking an emancipatory future free from neocolonial domination.

Related article:

It is noteworthy that in a letter expressing his condolences, Badiou emphasised that he cries “for the friend and the militant, and for the thinker and the human being”.

Shack dwellers’ movement Abahlali baseMjondolo said, “Baba Wamba understood that the oppressed have to organise themselves for their own liberation, and he understood that, as well as being open to the whole world, we also have powerful tools within our own culture and history to draw on in the struggle.”

Wamba was committed to emancipatory politics irrespective of who engaged in them, not to social status. Not many people would be remembered in this way by both the leading philosopher in France and some of the most committed and courageous grassroots activists in South Africa.

Wamba loved to laugh. On learning that he was a great fan of Franco’s music, I asked him some years ago why Franco had demeaned himself by writing songs extolling the virtues of Mobutu Sese Seko as a presidential “candidate”. I said it was understandable that he could not be critical of the dictator, but that surely there must be limits? Wamba replied, “Listen to the guitar, it is ironic!” And he laughed and laughed. I’ve been enjoying this irony ever since.