Long Read | ‘This was our Woodstock’

Concert in the Park in 1985 gave the vast crowd in Joburg a taste of what life could be in South Africa, and performers an idea of the sway they held over politics at the time.

Author:

11 August 2021

The idea of a stadium full of people enjoying a day of music may seem far-fetched in today’s physically distanced times, but much the same could’ve been said in January 1985, albeit for different reasons. South Africa was on the boil and months away from a state of emergency that would give the state free rein to commit unspeakable atrocities, as oppression and resistance were ratcheted up until the country was close to breaking point.

Musically, however, things had never been better (and arguably never would be again). Sensing an opportunity, record producer Hilton Rosenthal and Radio 702’s Issy Kirsch got rugby boss Louis Luyt to allow the use of Ellis Park stadium in downtown Johannesburg free of charge. Then they convinced 22 of the county’s top acts to donate their talent, as well as all the requisite stage, sound and lighting crew. The day came together in what was billed as a fundraiser for Operation Hunger, a Joburg-based non-governmental organisation established in 1978 that is still around today, providing relief against poverty and malnutrition.

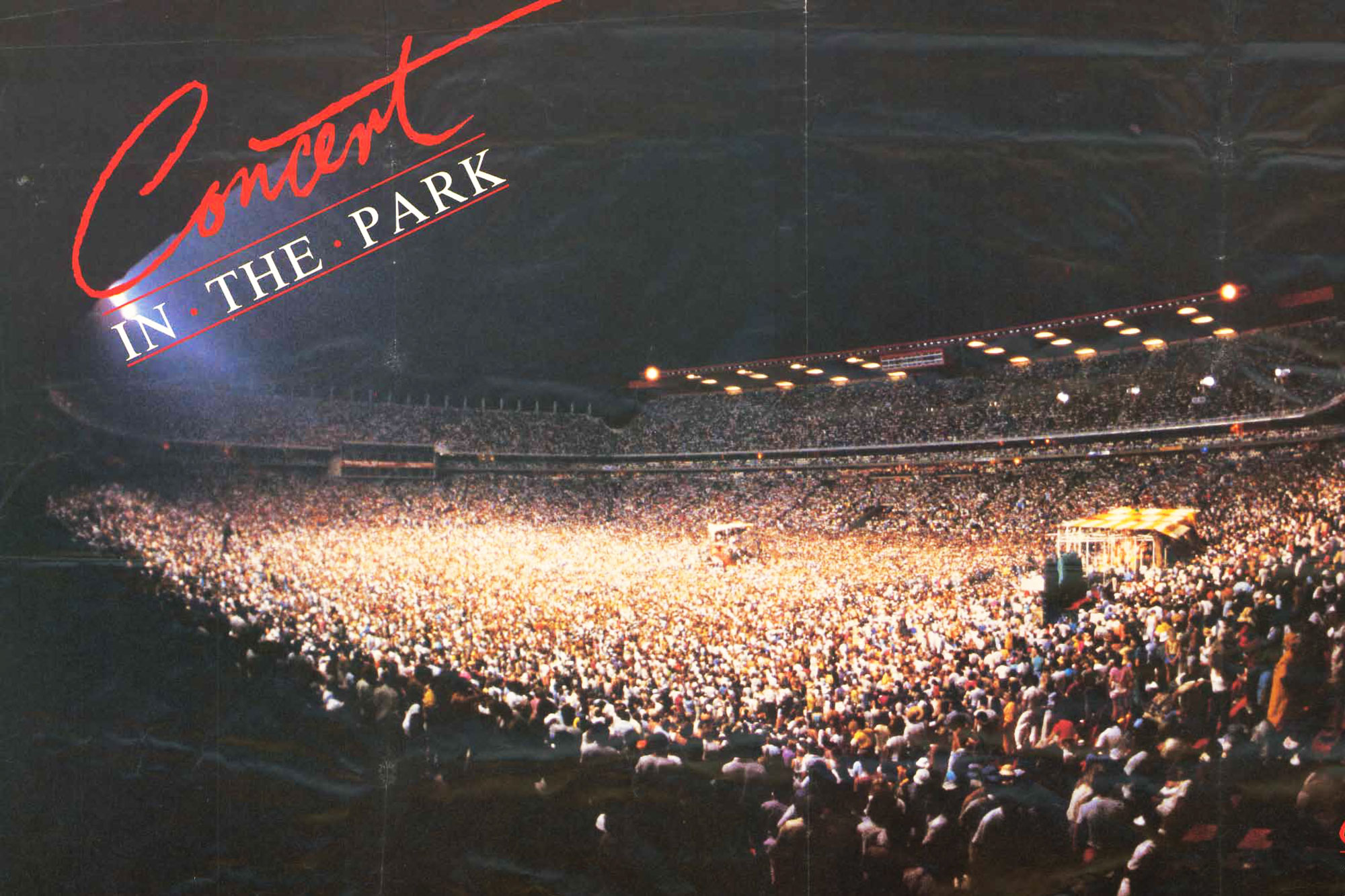

It became the largest single-day live music event this country has ever seen, with an estimated 125 000 flocking to the stadium on Saturday 12 January 1985, the majority of them paying to get in.

In the context of apartheid South Africa, what transpired defied even the wildest expectations of the organisers and the performers: a massive audience drawn together across race, all enjoying themselves for a worthy cause.

Returning to the scene

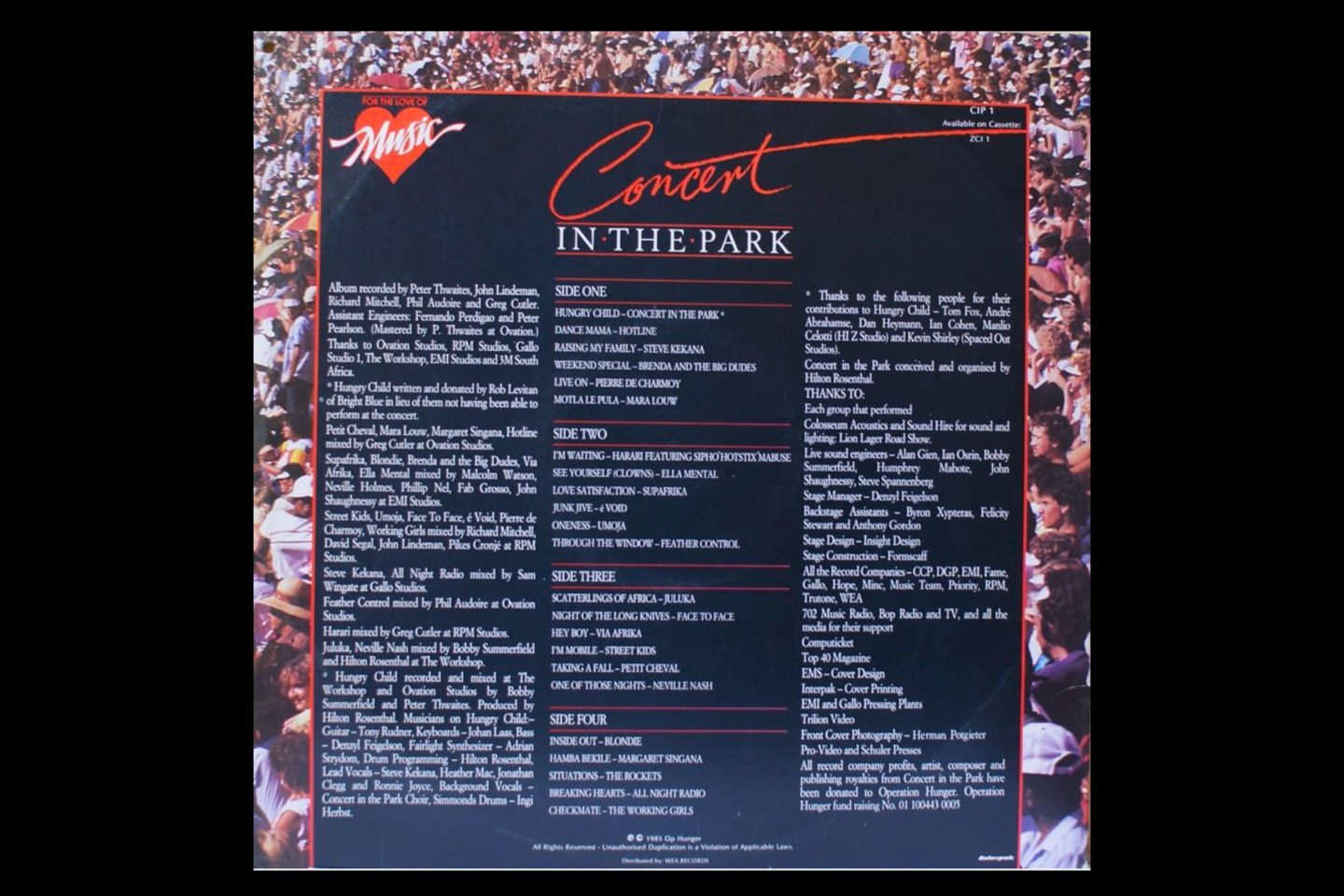

On a summer day shortly after the start of the new year, the day’s proceedings, performed by a line-up assembled in a matter of weeks, get under way. Each act plays a short set, although only one song of each survives in the official record: an abridged version of the concert released on vinyl and in videos later reposted to YouTube.

The first part of the concert proceeds innocently enough. Opening are Pretoria New Romantics Petit Cheval, fronted by Jonathan Selby, setting the tone for what’s to come. Neville Nash, one of the country’s biggest-selling soul singers since the late 1970s performs his new single, One Of Those Nights. Supa Frika, aka Henry Maitin, follows with his hit Love Satisfaction. Mara Louw’s version of Motla Le Pula (The Rainmaker) brings the spirit of the exiled Hugh Masekela to Ellis Park without dampening the weather. Ray Phiri’s pre-Stimela project Street Kids, featuring Nana Coyote (born Tsietsi Daniel Motijoane) and Paul Ndlovu, turn on the charm with their hit I’m Mobile.

Throughout this time, the audience is growing, but patches of red seats in the stands are still visible. By the time funk outfit The Rockets, led by “Little” Ronnie Joyce, perform Situations, the crowd is even starting to fill the spaces behind the stage – traditionally left empty in a show – a sign that by now things have reached a point far beyond what was expected. What follows are the golden hours that surely resonate strongest among the audience, each respective artist seemingly aware that this could be history in the making.

Underlying the biblical proportions of the event, Blondie Makhene, by this point already a veteran of the South African music scene, takes to the stage and injects the holy spirit into the audience: “Reach out and touch somebody’s hand, make this world better. (Inside, outside, touching you every day!)”

The oldest artist in the line-up, Margaret Singana, performs in her wheelchair – after having suffered a stroke while on stage in Joburg in 1978 – throwing herself into Hamba Bekile, in English known appropriately as We Are Growing (in 1986, the song would become the theme for the miniseries Shaka Zulu, starring Henry Cele).

Experimental rock band Ella Mental are up next. Their compelling singer Heather Mac asks the mass of humanity in attendance: “What’s this about a new direction, something that can help us grow?” The lyrics for their most famous song, See Yourself (Clowns), in this new context surely assume greater significance than the artists themselves could have ever expected or hoped for.

Disco-funk act Umoja, led by former Harari bassist “Om” Alec Khaoli and flamboyant Donovan Knox, take to the stage in their trademark spandex leotards, upping the theatrics by donning monster masks for their finale. Behind the fun is still a salient message: they perform Oneness, which is also the meaning of the band’s name in kiSwahili.

Via Afrika, fronted by Rene Veldsman on vocals and bass, up the energy further with Hey Boy, the perfect fusion of African groove and new electronic delivery. It is South African pop music at its innovative, evocative best. People are dancing together.

As the sun dips below the stands, Brenda Nokuzola Fassie – just 20 years old but already a household name – delivers her breakthrough hit Weekend Special with the backing band that had helped launch her career two years earlier, The Big Dudes. They playfully and seamlessly shift for a moment to CJB’s bubblegum hit Tonight I Need Somebody.

Next up, late-era Harari, the innovative Afro-rock group fronted by Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse on piano, work their way through the slow, churning I’m Waiting. “I’m waiting, let’s celebrate, just the two of us.”

Hotline follows, with 24-year-old PJ Powers unleashing Dance Mama on an audience the size of which has now reached epic proportions, several times the regular capacity of the stadium.

As darkness falls, Steve Kekana – who died unexpectedly in July – performs Raising My Family, a song with a distinctive and pioneering bass synth (crafted by producer Mally Watson) that had already topped the charts in Scandinavia, taken the singer to Europe the previous year and been covered by Jamaican singer Precious Wilson of Eruption fame.

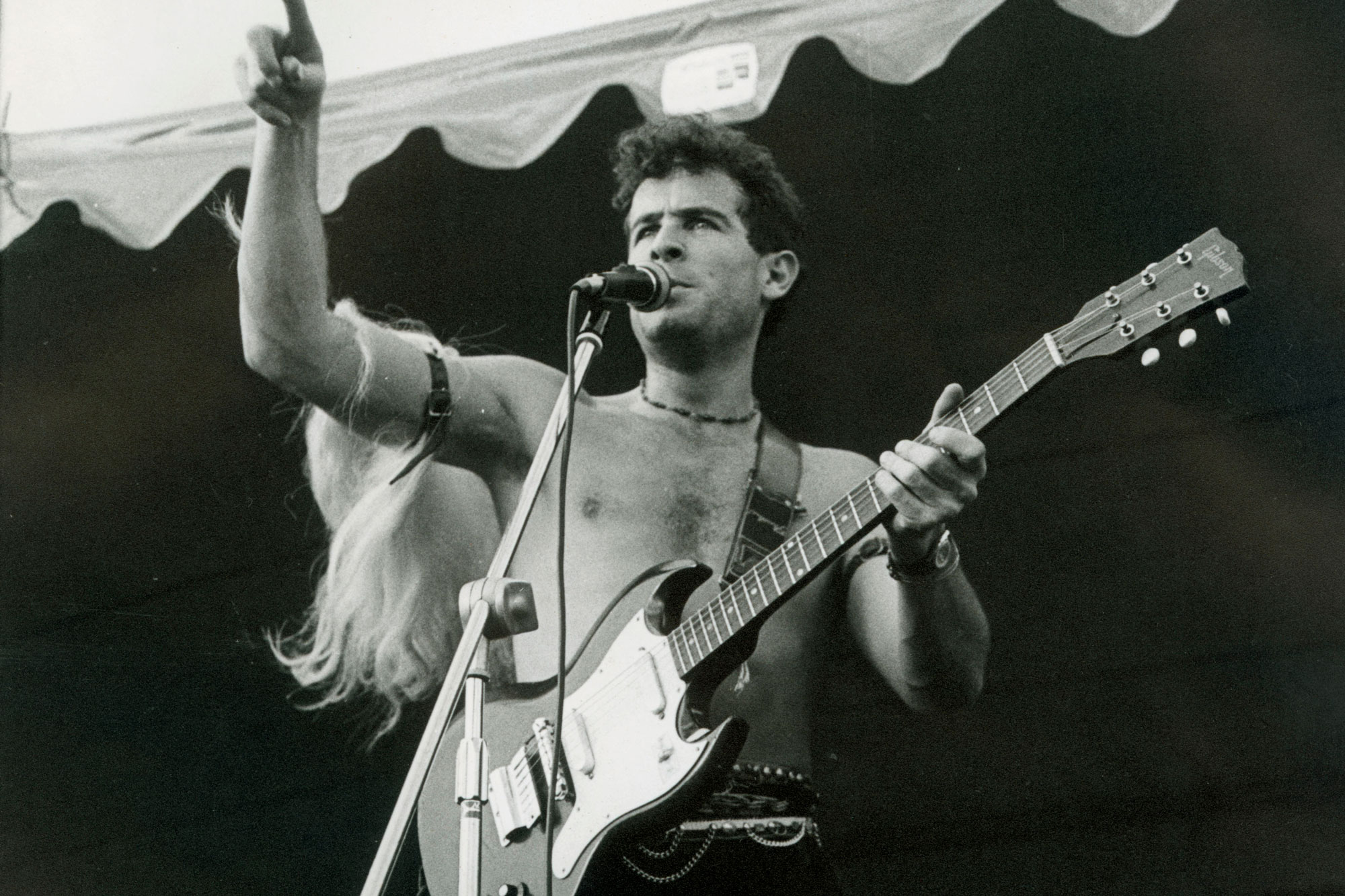

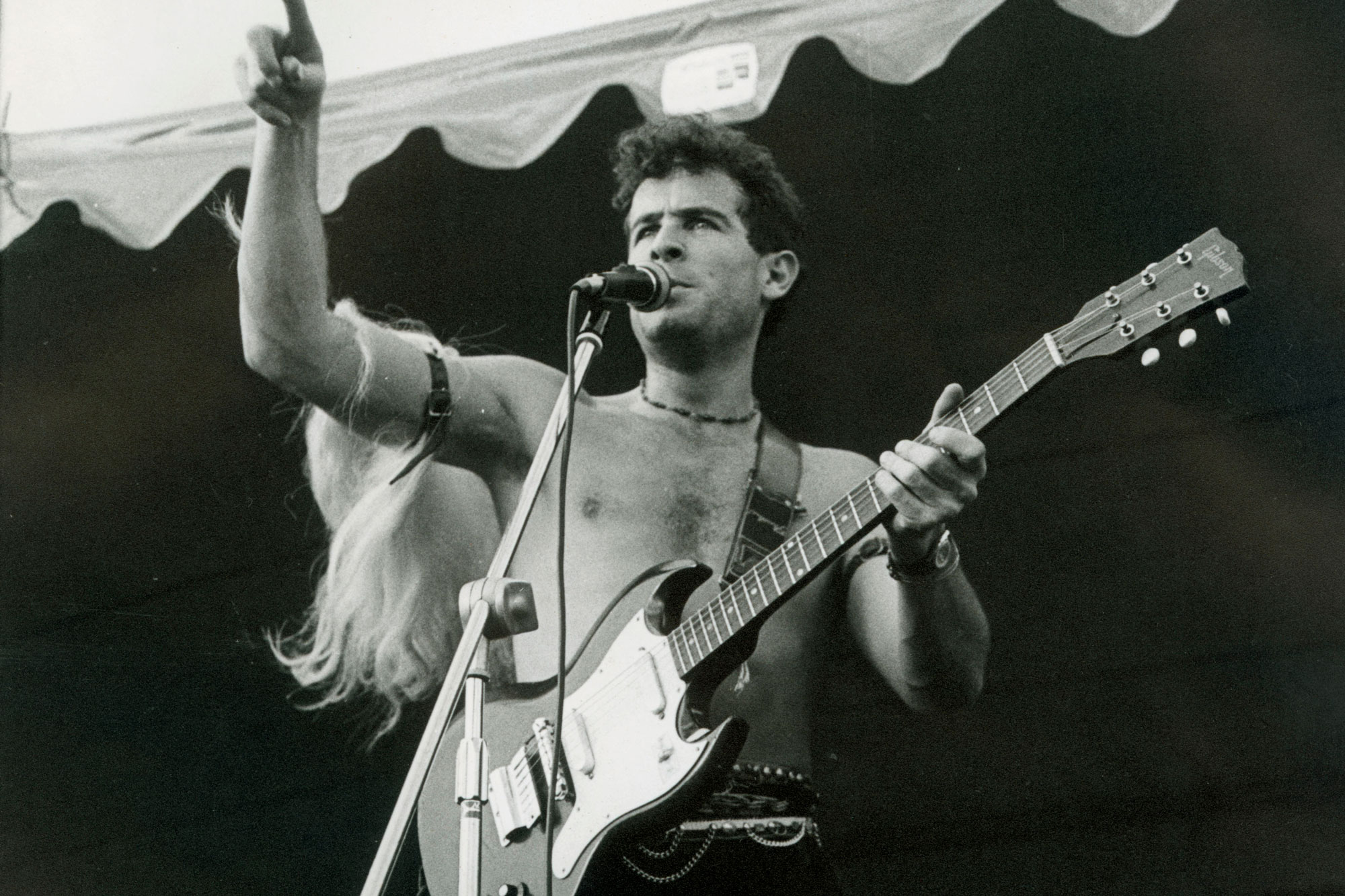

The concert reaches a crescendo with Juluka, a hugely powerful political and cultural presence at the time. Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu have the vast crowd enraptured as the band play their anthemic hit, Scatterlings Of Africa.

After Juluka and into the final part of the evening, the size of the crowd wanes as more middle-of-the-road white acts such as Feather Control, Pierre de Charmoy, Face to Face, The Working Girls and All Night Radio perhaps remind many in the audience that the party’s over and it’s time to negotiate the often perilous trip home. Later, éVoid close the day with renditions of Shadows and the funk-filled Junk Jive, which still incites electric excitement among the remaining crowd.

The politics of dancing

Though the popularity and quality of acts that day would have contributed to the concert’s success, organisers of live events then trod a perilous line, often needing approval from one or both of two opposing sets of authorities, or risk being shut down. With a line-up catering equally for Black and white audiences, and artists being a deeply heretical idea at the time, at one point the event going ahead at all was touch and go.

Nash recalls: “Surely there were a lot of political things happening … and there were meetings because some of the musicians were strong into politics. They were meeting [with comrades] and saying, ‘The show might not go on’ … and I was waiting. Some of the artists were saying, ‘Hey, it’s off, we’re not gonna do it.’ So I approached the organisers of the show and asked what’s happening. They said, ‘No, it’s still on.’ I said, ‘Man, I haven’t heard anything [about it being cancelled], so I’m on!’”

Views differ in terms of the day’s legacy. Clegg recalled in a 2010 interview: “Concert in the Park was a momentous event because it was the first time that all these various genres of music came together in a huge, 12-hour concert … It’s the biggest concert that ever happened in the country, and I think it still holds the record.

“But for me, it was the beginning of the idea that we could form an alliance as musicians. And later on, in 1986, we started to debate the idea of an alliance, and it was launched at the end of 1986, the South African Musicians’ Alliance … The Concert in the Park was the first time that we had … the possibility of all being together in one place. For me, it was a watershed, breakthrough moment.”

Ian Osrin, as a sound engineer for Colosseum Acoustics, witnessed the day from the sound booth perched on scaffolding over the audience in front of the stage. He remembers it as one of the biggest days in South African music, but one that has since been almost entirely forgotten.

“It was 1985, the same year of [then president] PW Botha’s Rubicon speech. All hope had vanished … Would there ever be a peaceful resolution? Never, it was the end. And yet that concert took place in the midst of that. The most joyful, most happy coming together of people across every culture, enjoying each other’s music. How perfect.

“That day proved something unequivocally, and probably paved the way in many senses to the success of the elections later … It was proof … of Black and white people being able to coexist extremely peacefully, happily, have a great time together, under circumstances that were impossible.”

Mabuse sums it up: “In my view, the concert was more than just an exercise of attraction [between people of different races] but rather a mega statement towards apartheid at its height.”

No more heroes

Most of the artists on stage that day, performing their hits in front of such a massive and appreciative crowd, perhaps seemed destined for bigger things. A few succeeded; most did not.

Within a year and a half, Ndlovu from Street Kids had died in a car accident. Juluka soon disbanded (later evolving into Savuka). éVoid left South Africa to avoid conscription. Petit Cheval split in 1987. Ella Mental and Via Afrika attempted to crack the American market but failed.

With the passing of time, more have died: Singana in 2000, Coyote in 2010, Joyce in 2013, his bandmate Molly Baron in November 2020, Hotline keyboardist Ron ‘Bones’ Brettell in 2016. More famously, South Africa in recent years bade farewell to Clegg in 2019 and Phiri in 2017, losses from which the industry will never recover but which overshadow the many others who never reached their level of success. And now Kekana, too, has died.

Concert in the Park was an extraordinary day. There is a temptation to romanticise it and risk overplaying its significance. To claim that this was the day on which South Africa broke down its racial barriers would, in hindsight, prove an exaggeration. But it did show many musicians the power they had and the role they could play in the struggle against apartheid, and solidify their position against the state. The struggle was still far from over, though, and the state would continue to co-opt musicians. The Azanian People’s Organisation (Azapo) would target Makhene, Kekana and Abigail Kubeka for their participation in state-sanctioned single, the notorious Info Song of 1986.

Yet returning to videos online, one can still get a sense of the magic in the air that day. It was a rare day when people triumphed over a state determined to divide and repress. A day that belongs, still, to the more than 125 000 South Africans who were there.

For young people in particular, whose lives until that moment would have largely been controlled and kept separate from perceived others by authorities hell-bent on maintaining this perverse status quo, music now offered a way of seeing each other.

A perfect storm

Osrin attests to various factors that could have resulted in any number of disasters that day: minimal security or crowd control, an inadequate sound system, an overloaded power supply, the threat of thunderstorms…

“On the Sunday when we went to strike, pack up, we came back to find we couldn’t pull the plugs out the wall because they’d overheated to the point of welding themselves into the sockets …. because we were drawing far too much power for the sockets we were using … If you look at the line-up, it’s quite extraordinary that we dealt with it … The PA should’ve packed up at 6 o’clock.”

Six months later, Live Aid on 13 July 1985 would draw 72 000 people to Wembley in London, United Kingdom, and 90 000 to JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, United States, on a day remembered as a turning point for the role of musicians in social causes. But what had already taken place at Ellis Park was a cultural lightning rod arguably more akin to Woodstock in 1969.

“It was our Woodstock,” says Osrin. “Because Woodstock was exactly the same. Chaotic, ridiculous, shouldn’t have happened. Nobody expected it [to work out] but it did, and it never happened again … because it’s [one of] those moments in history.”

For a day, the impossible became real. Because services were donated free of charge, the commercial risk was minimal. And because it was done in the name of hungry children instead of a political cause, there was sufficient buy-in from all parties to make it all possible. Promoters would attempt to recreate its success with other stadium concerts, but they’ve never succeeded in coming close to the scale and spirit of the Concert in the Park.

However, perhaps because the Ellis Park event was not associated with a political movement such as the United Democratic Front (UDF) – the vast network of organisations that reinvigorated the anti-apartheid struggle in the 1980s – historians have been reluctant to afford it a place in collective memory. Perhaps given the lack of explicit politics that day, we see no reason to commemorate it. Perhaps because the SABC wasn’t involved means it hasn’t been preserved in popular consciousness to the same extent, through rebroadcasts over the years.

The value of Concert in the Park is less tangible, more visceral and personal. It lives on in those who were there. The memory remains pure, uncorrupted by annual commemorations, unco-opted by politicians, undefiled by corporate interests. Just a moment in time. To some a harbinger of what was to come. To others, a fleeting glimpse of what could have been but remains elusive a generation on from that day.