Long Read | The slow decline of West Indies cricket

Reigning supreme in the 1970s through to 1995 with Test play that kept the world spellbound, the island nations’ cricketers are now unlikely to reach those heights again.

Author:

22 September 2021

“We West Indians are a people on our way, who have not yet reached a point of rest and consolidation,” wrote CLR James in his classic cricket book-cum-anatomy of colonialism, Beyond a Boundary. “We are moving too fast for any label to stick.”

This was truer than he knew. Like one of Delphi’s double-edged oracles, James foretold the scaling of the dizzy heights, and, although he could not know it, the equally swift, head-over-heels tumble into the abyss.

James died in 1989. What would he have made of the calamity that has befallen West Indies test cricket since the mid-1990s? And those in South Africa for whom their long, glittering reign meant so much? What are they – we – to make of it?

During South Africa’s Test series in the Caribbean in June and July, the deficiencies, particularly in batting, were once more starkly in evidence. It is respectable now to support our countrymen, but one would so much have liked Jason Holder’s low-voltage outfit to spark up!

After that defeat the islanders fell to seventh in the world Test rankings, ahead only of Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Zimbabwe. They have tended to do better in one-day and Twenty20 formats, but for the players and the cognoscenti, it is the five-day game that matters.

James witnessed, in his last years, the most extraordinary decade of the game. Under the leadership first of Clive Lloyd, then of Vivian Richards and briefly Richie Richardson, the West Indies did something without precedent and unlikely to be repeated: for 15 years, between 1980 and 1995, they lost not a single Test series.

A tie that binds

Lloyd and Richards succeeded in binding 13 major islands and territories spanning 2 900km, infusing them with a burning will to win and fostering a belief in the Caribbean, and the wider world, in their incontestable ascendancy. Political union had failed with the collapse of the West Indies Federation in 1962, but cricket kept the idea of the West Indies as a nation alive.

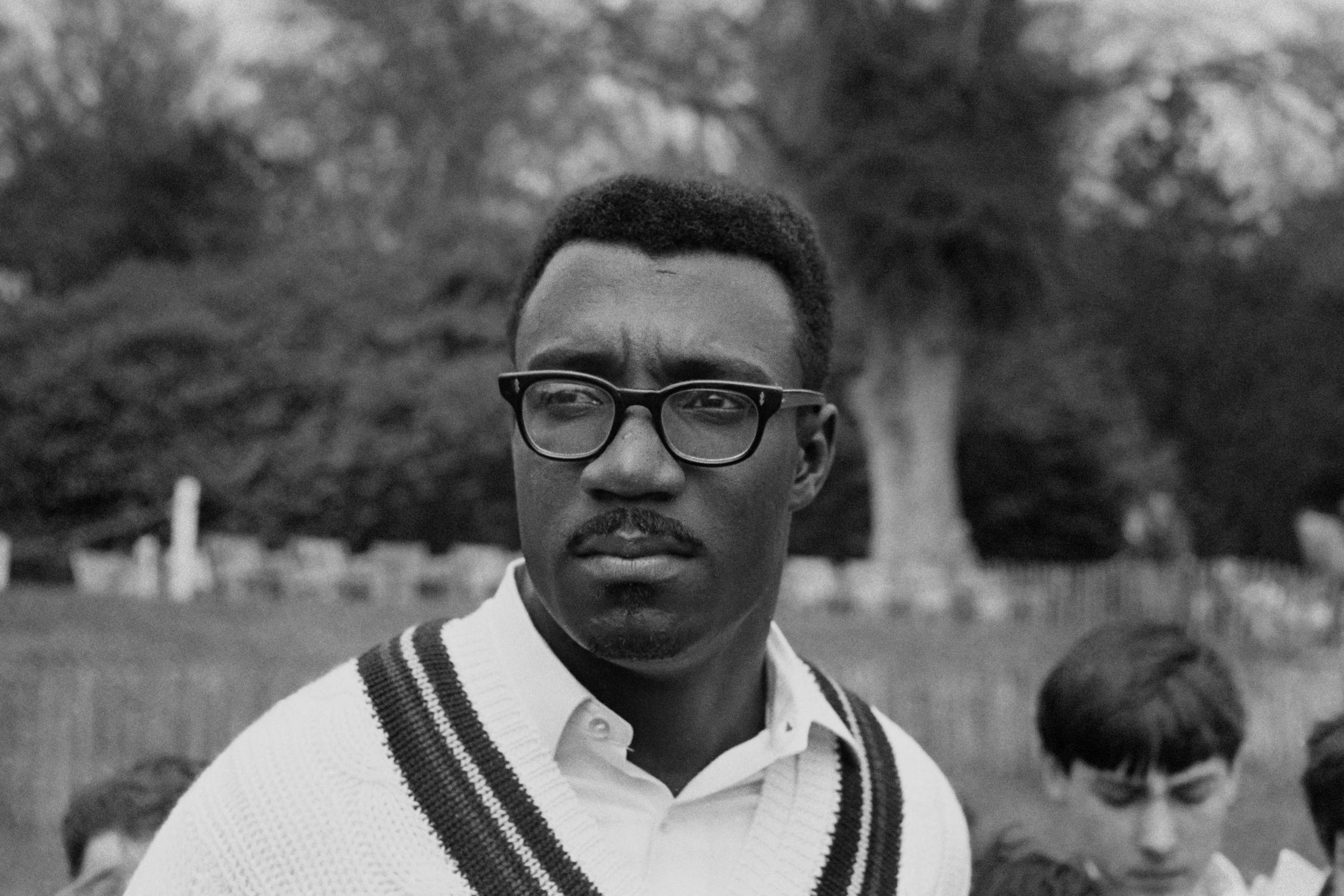

It was Lloyd, affectionately known to his troops as “Hubert” (his middle name), who changed everything. Tough and ruthlessly competitive behind his avuncular spectacles, he was taught a searing lesson by the 1975-1976 tour of Australia, when the West Indies wilted to a 5-1 defeat under a brutal short-pitched barrage at close to 160km/h from Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson, who took 56 wickets between them.

He has been pictured as scouring the Caribbean for a similar speed machine, but he already had two of its moving parts in Andy “Hit Man” Roberts and Michael “Whispering Death” Holding, so nicknamed for his soundless, pantherine approach to the wicket.

Express pace was not enough, the Australians had taught him – of equal moment was the bowler’s outlook. Lillee publicly proclaimed that his object was to hit batsmen under the ribs and hurt them so much that they “didn’t want to face me any more”; Thomson wanted to see “blood on the pitch”.

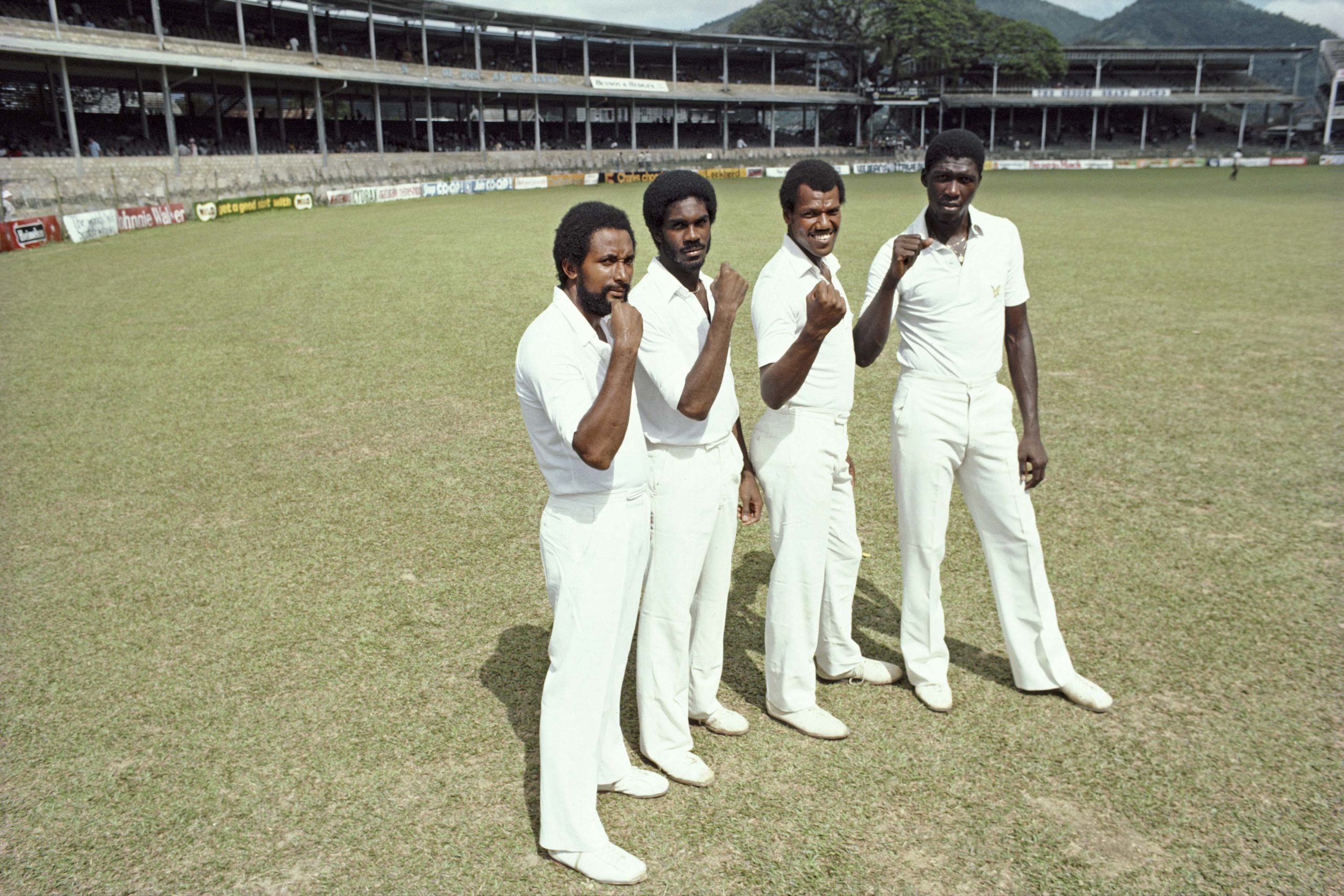

To Holding and Roberts, Lloyd added “Smiling Assassin” Colin Croft – once described as “all snarling aggression” – and “Big Bird” Joel Garner, an off-field charmer but in some ways the most menacing of the four, with his steepling height (2.032m) and bounce.

Lloyd’s method was straightforward. Dropping all pretence at gentility, he consigned the 309 Test wicket off-spinner Lance Gibbs – his cousin – to the ash heap of cricket history and proceeded to rotate his fast men in a pitiless cycle in every game.

In 1978, they were joined by Malcolm Marshall, another supremely gifted fast man who regularly hit batsmen, famously rearranging Englishman Mike Gatting’s nose and – it is ghoulishly claimed – leaving a bone splinter in the ball. Between them, they took more than 1 200 Test wickets.

It is pointless complaining that Lloyd violated the spirit of the game, as many English players and journalists habitually did. To counter “the four horsemen of the apocalypse”, it was even proposed to change the laws of cricket – for example, by drawing a line across the wicket and no-balling any delivery that fell short of it.

England had deliberately deployed Harold Larwood and Frank Tyson to terrify the Australians. The reality is that any international side with bowlers of high pace and blood-curdling nastiness will not scruple to use them.

Lloyd’s policy paid off handsomely. Between 1976 and 1995 the West Indies won six Test series against Australia, losing none, with an overwhelmingly positive balance in individual matches of 14-3.

A long time coming

The West Indies’ rocket-like lift-off after 1980 is something of an optical illusion. Like the Bene Gesserit’s messianic genetic engineering in Dune, the miraculous birth had a slow gestation. It began in the 1930s with Sir Learie Constantine, whose book Cricket and I demanded an end to race-based selection.

James describes how it was nourished in the post-war period by the rise of the West Indian middle classes – two of the “Three Ws” that bestrode the crease in the 1950s, Frank Worrall and Clyde Walcott, were sons of relative prosperity – and West Indian exposure to English conditions in the Lancashire League. Everton Weekes was the third “W”.

The hardened tradition, which James adamantly resisted through the columns of The Nation newspaper, was Black players under white leadership. After Worrall was installed as the first regular Black captain, the team had its first transient spell of world supremacy, winning from 1961 to 1967 against India (twice), England (twice) and Australia.

Related article:

In that era of slow-scoring wicket preservation, mocked by James as “the welfare state of mind”, the West Indies under Worrall were seen as breathing new vitality into a stagnant undertaking. The Three Ws hallmarked a dashing technique, including wristy, swashbuckling strokeplay – driving “on the up”, the right-over-left flick from outside off through midwicket, and the back-foot cover drive off a ball of near-yorker length – that thumbed the nose at the ossified canons of orthodoxy. Walcott, in particular, bequeathed to Lloyd and Richards the idea that batsmen should not take a step backwards and that the ball was there to be bludgeoned, not fended off.

The media labelled this “calypso cricket”, with just a condescending hint that the players were flamboyant, “naturally gifted” entertainers, like the minstrels of yesteryear, for whom winning was secondary. What the Lloyd-Richards axis did was give it a backbone of steel.

More than a game

For this to happen, another ingredient was added to the alchemical mix that would be decisive in both the rise and fall of West Indies cricket: nationalist politics. In Beyond a Boundary, James drives home the point that cricket in the West Indies was far more than a game – it crossed “the boundary” into the hearts and minds and the cultural and political life of the mass of ordinary islanders. “The cricket field was a stage on which selected individuals played representative roles, which were charged with social significance,” he wrote.

For the team of the 1980s, it was similarly symbolic. The mental atmosphere was the product of three decades of decolonisation, often through armed resistance, and continuing revolutionary wars in southern Africa.

Liberation was also in the air in the Caribbean. Between 1960 and 1980 the number of independent island states grew from three to 16. Black pride found a defiant voice in Rastafarianism and the anthems of Bob Marley, who told the islanders: “Emancipate yourself from mental slavery/ None but ourselves can free our minds…”

The urbane Worrall, “draped with … diplomatic graciousness”, as James put it, made “a public entry to the comity of nations”, dramatised by the public send-off of the 1960-1961 West Indians when a quarter of a million admiring Australians lined the streets of Melbourne. Lloyd’s outlook was very different. He wanted to subdue the Australians, not seduce them.

The Melbourne send-off was misleading. Michael Holding has told of the crude racial abuse from the ockers on the terraces; racial sledging on the field under Ian Chappell, a man of much coarser fibre than Worrall’s opposite number, Richie Benaud, seems to have been standard practice.

Beating the former colonial overlord was an even higher priority, especially after the ill-judged pledge by England captain Tony Greig – a white South African – to make the 1976 West Indies “grovel”. To achieve this, he said that he would call on the services of Yorkshire hard man Brian Close.

The West Indies took the series 3-0. But by far the most vivid projection of their revanchist state of mind was Holding’s bouncer fusillade at the hapless Close during England’s second innings at Old Trafford.

Holding, bowling at extreme pace, repeatedly struck the balding 45-year-old, who after one blow to the chest staggered and just avoided collapsing. In the political context, the onslaught seemed to reflect Frantz Fanon’s idea that the oppressed heal themselves through violence against the oppressor.

“We took that [Greig’s grovel threat] very, very seriously,” Richards said in the documentary Fire in Babylon. Lloyd told the dressing room: “We don’t need to say much. Our man on the television said it all for us. We know what we’ve got to do.” The umpire upbraided and waved his finger at Holding; from the slip cordon Lloyd pointedly said nothing.

A political mission

Richards, captain in 50 Tests between 1985 and 1991, saw his mission in an even more decidedly political light. Historian and University of the West Indies vice-chancellor Hilary Beckles writes that he “unleashed on the field of play a level of historical awareness of the West Indian struggle for sovereignty that touched the souls of disenfranchised millions, who felt the power of his mind and the strength of his convictions”.

His personal bearing and batting style loudly proclaimed Black pride. There would be no concessions, no retreat; aggression, on principle, would be met with counter-aggression. He was reggae artist Peter Tosh’s “steppin’ razor” personified. Refusing to wear a helmet or body armour, he sauntered to the wicket with studied nonchalance, insolence almost, in his trademark red West Indies cap. Once he had taken guard, he was capable of some of the most destructive batsmanship the game has seen.

The story goes that after he had played and missed several times in an English county game, the bowler unwisely snapped: “Let me help you. It’s round, red and weighs five and a half ounces.” Richards promptly hit the next ball out of the ground, with the chaser: “You know what it looks like, you go and find it…”

The 1976 tour of England was one of prodigies – Greig’s settler colonial brashness brought out the best in the West Indian. In six Test innings Richards made 825 runs – including a century, a double century and a near-triple century – at the scarcely credible average of 137.5.

Richards called reggae his “battle music” and in the middle wore the Rastafarian red, green and gold on his wrist. Like Marley (“Rastaman don’t work for no CIA”), he was more than a Caribbean nationalist – he was a radical nationalist of the Global South.

In his autobiography, Hitting Across the Line, Richards says he believed “very strongly in the black man asserting himself in this world, coming as I do from the West Indies at the end of the colonial era. I identify with black power, [Rastafarianism] and all the movements of black liberation.”

He revealed that he was offered $1 million to tour South Africa with other West Indian boycott busters, but said: “I could not go as long as the black majority … remains oppressed by the apartheid system … I would be letting down my own black people and I would destroy my sense of self-esteem.”

Beckles also quotes him as saying that he would like to be remembered as a cricketer who carried his bat for “the liberation of Africans and all oppressed people everywhere”.

The spell is broken

After Richards’ retirement, it was the Australian Waugh brothers who broke the spell. At Sabina Park in Kingston, Jamaica, on 29 April 1995, the new generation of West Indian bowlers was put to the sword, Mark making a century and Steve a double century in a 231-run partnership that clinched the Test and the rubber. The Frank Worrall trophy was back in Australian hands – and has remained there ever since.

What did the most damage to West Indian self-esteem was the casual and spiritless nature of the surrender. Their second innings lasted just 69 overs, after the Australians had been at the crease for 160.

Years of effortless dominance had put swank into the step of the side’s followers, both in the yaads of Montego Bay and the mean streets of Lewisham and Birmingham. In 1984, after a 5-0 clean sweep against England at the Oval, they had swarmed on to the field chanting, “S’easy! S’easy!”

Beckles writes that West Indians were keenly alive to the longer-term symbolism of the Sabina Park defeat – “intellectual decline, cultural degeneration and the collapse of nationhood”. No less a figure than Jamaica’s socialist prime minister, Michael Manley, demanded an analysis of the setback and what it said about the loss of organisation and focus that had marked the Lloyd-Richards era. The titans had turned to dust, and something unfamiliar and Lilliputian had taken their place.

Related article:

Later that year, a tour of England was almost wrecked by player dissension and indiscipline, fanned by the self-centred and divisive genius of Brian Lara. He asked to travel separately from the team, clashed with the captain, Richardson, revealed that a bat manufacturer had offered him a £3 million sponsorship, stormed out of a team meeting shouting “I retire”, and went missing for three days. He also made three Test centuries.

Lara went on to scandalise the public and the older generation of cricket luminaries like Croft and Holding by refusing to play in a one-day tournament in Australia, saying he was tired and needed to rest.

Chris Gayle has provided a snapshot of how Lara’s preoccupation with his personal statistics undermined his captaincy. When Gayle passed the 300 mark in a Test, there was no encouragement from the skipper, no “do it for the team” – only worry that his own 375-run record was under threat. “Every time Brian came out to see my score getting closer to his record, he looked more and more worried.”

Mauled and humiliated

From that point, there would be no return. At the 1996 World Cup, the former invincibles were mauled by 500-1 debutants Kenya. The Telegraph, which for years had denounced the West Indies’ “bouncer thuggery”, savoured their comic discomfiture at the hands of the semi-amateur East Africans. After several manic swishes, Lara was somehow caught behind by the bespectacled and fumbling Kenyan wicketkeeper Tariq Ali, “wearing a headband and double chin”.

“The ball sank somewhere in his nether regions, while the gloves clutched desperately, trying to locate it,” sniggered The Telegraph correspondent. “Then, glory be, it reappeared in his hands, to be held aloft in triumph and relief.”

Two years later, on the eve of the West Indies’ first tour to South Africa, Lara, now captain, led a player uprising over pay and stood up Nelson Mandela at the airport. Sacked and then reinstated by the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB), he eventually rejoined the side, but to no avail – the West Indies were humiliatingly “blackwashed” 5-0.

Since then, they have lost every one of seven series against the South Africans, home and away. Against Australia they have not won a Test, let alone a rubber, for 20 years.

Related article:

Beckles complains about the “fluke” theory of West Indian ascendancy, which he ascribes to unctuous English commentator Mark Nicholas, denouncing it as an insult to the players and the West Indian people.

Nicholas cannot mean pure, random contingency – cricket has its chance elements, but the longer the form the smaller the part they play, and the truer the reflection of the balance of cricketing power between nations. Five-day matches, with two innings per side, really are “tests”.

What he may mean is that the coming together of such a radiant galaxy of cricketing talent under such charismatic leaders over such a period was a freak occurrence. The gold-producing alchemy needed more than a battery of terrifying pacemen. The West Indians had, between 1974 and 1994, eight batsmen with Test averages of 40 or above and Richards, with an average of over 50, the batsman’s purple toga.

Battling to bat

Test match batting – which requires crease occupation and long-range concentration – has been the bane of the post-1990s West Indies sides. No regular batsman in their current 11 averages more than 33 and four average less than 30.

The rise of the T20 format and the Indian Premier League (IPL) has clearly accentuated this by offering far richer rewards for far less physical and mental exertion. Gayle is a case in point. A superlative talent with two Test match triple 100s to his name (one against South Africa), he has a test average of 42 but contemptuously kicked away the five-day game seven years ago.

While captain from 2007 to 2010 he arrived just two days before the start of a Test in England, delayed by his IPL commitments. Under fire, he said he would “not be sad” if Test matches disappeared and were replaced by the 20-over “hit and a giggle”, as Australia’s Ricky Ponting scornfully termed the T20 format.

A short-form freelancer, Gayle has sold his power-hitting services to Australia and Bangladesh. He is a former ragpicker raised in a Kingston shack by parents who could not pay for his schooling and often could not feed him.

Nowadays, “Six Machine” – as he calls himself in his autobiography – lives in a three-storey mansion with a rooftop swimming pool and a view over Kingston port towards the distant Blue Mountains. His net worth is estimated at $15 million (about R225 million). Lara, one of the world’s five wealthiest cricketers, is valued at $60 million.

From across the Straits of Florida came other corrosive influences: American professional sport and hip-hop “bling” culture, with its greed and self-vaunting exhibitionism. The world narrowly missed losing the sublime fast bowling gifts of Curtly Ambrose – rated by many who faced him to be the most complete paceman of the modern era – to the National Basketball Association.

Money matters

Money has been at the root of the interminable squabbles between management and players, for which the WICB (now Cricket West Indies) bears some responsibility. A player strike over pay this month scotched a tour – to India – for the third time in five years. Reacting, the Indian board has threatened to bar West Indian players from the IPL and suspend all future Indian tours to the Caribbean. It may also sue, toppling the rickety finances of Cricket West Indies.

Another example, from 2005, speaks of the hard-ball reflexes of both players and management. Seven players, including Lara, signed sponsorship contracts with British telecoms giant Cable & Wireless, but the WICB’s new sponsor, Ireland’s Digicel, would not allow its rival’s logo to feature on their shirts. Deadlock. The seven stayed on the bench for the first Test against South Africa.

And yet… the lure of the US has always been there, and the IPL only began in April 2008, long after the rot set in. For Beckles, the pay wrangles and strikes, Lara and Gayle, are symptoms of a deeper malaise – the rise of a globalised, money-driven sporting culture and the demise of the “second paradigm” of post-war cricketing nationalism in the Caribbean (the first paradigm being cricket under the Empire).

“The idea of playing for one’s country as the ultimate status that drives player motivation has become obsolete in the streets of Caribbean towns and rural villages,” he comments. “Players drawn from economically dispossessed communities … exposed to … high unemployment, police brutality, drug trading and endemic violence have asked the question: ‘What has my country done for me?’”

Related article:

Cricketers of the post-nationalist “third paradigm”, such as Lara, see themselves as “apolitical, transnational, global performers who desire to maximise their earnings in an attractive market … [They] wish to unhinge their performance from … the 1950s and 1960s’ political project of nation-building.”

The effect of such career-minded individualism has been to break down the team’s unity and sense of group purpose. To this can be traced the waning of the will to win and lack of fight in adversity so often bewailed by the West Indian public and cricketing elders. The pursuit of quick rewards has taken its heaviest toll on Test batting, a technically exacting art that takes endless time and commitment to master.

The WICB, ironically, promoted the decline by opting, after Viv Richards’ retirement, not to elevate his like-minded peer and natural successor, Desmond Haynes, to the captaincy. (Haynes once rounded on Australian keeper Ian Healey with his bat raised after a racial slur from behind the stumps.) Journalist Robin Marlar remarked that the board felt “it was time that the leadership … shifted its centre of gravity away from Black activism towards the mainstream of the international game”. It was to a “younger and less confrontational” Richie Richardson that the leadership devolved.

Loss of identity

What has clearly faded is the intensely close and single-minded team solidarity nurtured by Lloyd and Richards, the sense of being West Indians against the world – and especially the white world. After the 1995 debacle in England, the manager, Worrall’s former pace spearhead Wes Hall, penned a 100-page report in which he bewailed the weakening of West Indian identity within the squad.

The Hall Report listed other ego-driven aberrations: abandoning the side, deep-seated conflicts between players, disrespect for the decisions of the captain and management, abuse of the WICB via the media and the refusal to sign autographs.

Trinidadian-British broadcaster Trevor McDonald took up the theme, writing in The Observer that long submerged island parochialism appeared to be reasserting itself, to disastrous effect. For Barbadian journalist Angus Wilkie, the players were being asked to perform “in a void, without any unifying force”, in contrast with those of the 1960s and 1970s who were animated “by a hope and vision of West Indian [political unity] in a short space of time”.

It is significant that while Worrall is a revered figure across the region, with memorials in many places beyond Barbados, where he was born, Lara is honoured principally through a statue in Port of Spain, Trinidad, his home island.

In some ways, the lot of the West Indian cricketers has improved in recent years, and there are, from time to time, flickers of a minor resurgence. Former West Indian captain Shivnarine Chanderpaul has said that, unlike in his day, modern players have central contracts and their travel expenses paid.

There have been proposals for how to end hostilities between Cricket West Indies and the other interest groups, including players, business, the media and retired masters of the game keen to help but who are passed over in favour of foreigners.

In 2019, Beckles called for a “stakeholder council” to which the board’s president would account once a year, and for the board to underwrite a cricket academy based at the university, rather than arguing, obtusely, that its job is “to produce cricketers, not professors”. But even if the management dysfunction is rectified, it is hard to see the West Indies ever being more than a mid-table Test team.

Nothing fires up people more than the idea that the collectivity they identify as theirs, racial, national, ethnic or religious, needs their service and self-sacrifice. Of course they expect to be paid, but at a deeper level Indian, Australian and English cricketers are primarily driven by national consciousness.

For a period in the 1980s and early 1990s, there was a unique convergence of talent, leadership and nationalist political passions in the Caribbean. It is unlikely to happen again. The West Indies have become cricketers without a cause.