Long Read | The officers who interrogated Aggett

The testimony and cross-examination of apartheid-era police who interrogated activist Neil Aggett reveals the mindset of the feared Security Branch officers who covered up his death.

Author:

22 January 2021

In 1981, Martin Johan Naude was a 31-year-old lieutenant attached to the Security Branch in East London. Like many white, working-class Afrikaans men whose families did not have the means to send him to university, Naude joined the police after high school. The police and other branches of the apartheid civil service offered young men like him job security without the need for a tertiary qualification.

Naude was an able, focused member of the Security Branch who did his work diligently and without, as he insists, relying on nefarious methods such as torture and assault. He took exams regularly as he climbed the police service ladder, but says he did not receive any training in interrogation techniques or torture methods.

He disputes the accounts of former security police such as Paul Erasmus, who told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and other inquests that they did. He was also a keen sportsman who participated in the police’s rugby and cricket leagues.

Related article:

In October 1981, Security Branch divisions across the country received a notice from Major Arthur “Benoni” Cronwright, the head of the security police at John Vorster Square, and Brigadier Hendrik Christoffel Muller, the head of the security police in Johannesburg, saying their officers had made a large number of arrests and that the evidence these would yield would result in the “biggest treason trial in the country’s history”. But they needed assistance and requested manpower urgently to help interrogate the suspects.

Naude and fellow security police officer Captain Phillipus Olivier, who specialised in “labour matters”, were seconded to John Vorster Square. They arrived towards the end of October and Cronwright tasked them with assisting in the interrogation of Barbara Hogan.

Naude is now 71 with health issues, and dealing with the recent death of his brother from Covid-19-related complications.

He recalled over three days, from 18 to 20 January, for Judge MA Makume at the virtual resumption of the reopened inquest into the death of Neil Aggett that he did not know Hogan, or any of the other detainees arrested in the sweep, “from a bar of soap”.

The interrogation

Naude was quickly made to feel an outsider at John Vorster Square, “a reserve in a football match”, he said, with little evidence to work from. He did not know anyone at the police station. Over the next few months, Naude would spend his time between Johannesburg, compiling Hogan’s statement, and East London in the Border area of the Eastern Cape, where security forces were preparing for possible violence and unrest ahead of the declaration of independence of the neighbouring Ciskei homeland on 17 December 1981.

Contrary to testimony Hogan submitted during her trial in 1982, Naude denies that he was present when security police assaulted, threatened and used sleep deprivation and humiliation to torture her during her interrogation. The most he was willing to admit during cross-examination by advocate Howard Varney, who represents the Aggetts, was that he may have raised his voice during an interview.

“If I screamed and shouted at her, then I’ve got to apologise. But it’s not in my nature,” Naude said.

He “never threatened Miss Hogan and I can say that without a shadow of a doubt”, and if he had been involved in Hogan’s assault he “would’ve applied for amnesty”.

Naude became sceptical while interviewing Hogan that there was any evidence that would result in Cronwright and Muller’s “massive treason trial”. But when he raised this with Cronwright, he was told to shut up and do his job. This led to a rift between him and John Vorster Square’s notoriously volatile commander, he said.

Related article:

When Cronwright instructed Naude to begin interrogating Aggett on 15 December 1981, he found Aggett “easy to speak to” and claimed that the two men bonded somewhat because of their shared experiences as Eastern Cape “Border area men” who both smoked cigarettes.

Naude’s interrogation of Aggett continued on 17 December and then 21 December, when Lieutenant Stephan Whitehead, who had recently returned from an officers’ course, joined them. He testified that as an outsider, he deferred to Whitehead’s local expertise, but the latter never really interrupted his interrogation and served mostly as an observer.

Aggett’s statement was incomplete when Naude left for East London on 23 December, on leave for Christmas. As Naude recalled it, the process had been “cordial and friendly” thus far, with no complaints from Aggett.

The death of Aggett

When Naude returned from his holiday on 4 January 1982, the atmosphere between him and Aggett was the same, he said. But he discovered that in his absence, Whitehead had continued to interrogate Aggett with brutish railway police officer James van Schalkwyk.

It emerged at the original 1982 inquest into Aggett’s death that the detainee had been severely assaulted and tortured during the holidays. He had filed a complaint, but Naude said he saw no physical or psychological indication of this when he saw Aggett in January. Naude did accede that with the benefit of hindsight and in light of information to which he has had access in the past 39 years, it is “possible that he was assaulted on 4 January”.

In Naude’s absence, Aggett’s interrogation had entered a far more violent phase and Whitehead, under the auspices of Cronwright, had ostensibly taken over the case. Whitehead told Naude that the security police had completed the interrogation and all that was left for him to do was compile the statement, after which he was free to go.

Naude duly set about doing this. He and Aggett worked to place the events in his statement in chronological order, with Aggett volunteering to speed up the process by typing the statement himself. Whitehead demanded on 9 January that the statement be handed over, despite Naude’s objections that it was incomplete. Naude was told to return to East London.

Related article:

South African Police (SAP) Detective Sergeant Aletta Blom told Naude in February 1982 to return to John Vorster Square to provide a statement for Blom’s investigation of Aggett’s assault complaint. He arrived on 4 February and prepared his statement. He did not see Aggett and when he returned to the police station on the morning of 5 February, was told that Aggett had committed suicide by hanging himself in his cell.

Naude was shocked by the news and said it had created chaos at John Vorster Square. He was told that all SAP members who had contact with Aggett during his detention were to report to security police headquarters in Pretoria for a briefing. Naude submitted his statement to the police investigators on 24 February and was called to testify at the 1982 inquest.

His version of events then, which he relied on 39 years later, are the same as those recalled above. And as Naude pointed out repeatedly, advocate George Bizos, who represented the Aggett family in 1982, singled him out at the initial inquest for his professionalism and humane treatment of detainees. They included Hogan, Aggett and Elizabeth Floyd, who Naude had been sent to obtain a statement from at the Bronkhorstspruit police station where she was detained on 23 December 1982, the day he left for his Christmas holiday.

Looking back now, Naude admitted that it was possible he had been sent to see Floyd as a means of getting him out of the way so that the more intense and brutal period of Aggett’s interrogation by Whitehead could commence. He told Makume he believes that “if they granted me the opportunity to complete my statement, Dr Aggett would be alive today”.

Denials and training

Naude denied ever being shown a four-page addition to Aggett’s statement that former security police officer Nicolaas Deetleefs claimed – at the original inquest and in the initial proceedings of the reopened inquest last year – he had obtained from Aggett, in which the activist gave incriminating information about his comrades.

This document, which police lawyers offered as the catalyst for Aggett’s suicide, was not shown at the original inquest because of “national security concerns”. And when Deetlefs had the opportunity to produce it in camera last year, he refused. Naude was willing to admit that it was never produced because it was probably a fabrication.

Related article:

Naude went on to work for the security police’s C2 section, responsible for compiling information on terrorists and enemies of the state. This was often used to justify extrajudicial killings and attacks on activists by section C1, more commonly known as Vlakplaas.

He applied for and was granted amnesty by the TRC for one incident in the late 1980s, when he helped bury weapons near Krugersdorp that were then used as evidence of an ANC arms cache to justify a deadly cross-border raid by C1 against ANC activists in Botswana.

Naude enjoyed a successful career in the post-apartheid South African Police Service, serving as the director of its serious and violent crimes unit and retiring in 2009 with the rank of brigadier.

The good soldier

That may have been the end of the story of the good soldier Martin Johan Naude, who told the reopened inquest he was “a professional policeman. I did my work in the context of the legislation at the time for both the Nationalist and the ANC governments” and that he was happy to help the Aggetts in their quest for truth and had nothing to hide.

When Varney conveyed a message from Aggett’s sister Jill Burger, saying “I’ve lost all my family, we are the same age and time is running out to find the truth”, Naude thanked her and assured her, “I am testifying the truth and I regret my actions.”

But under increased pressure from the National Prosecuting Authority and Varney, Naude’s careful composure had begun to crumble by his third day of giving testimony on Wednesday and he grew irritable and frustrated.

He stated repeatedly and adamantly that he had never been involved in the torture or assault of any detainees and that he was not aware, outside of media reports, of security police who had been involved in torture or assault. He could only answer for himself and did not appreciate being made to feel that he was “answering for something like 700 people [former security police members] who are dead”.

Related article:

He repeated that, aside from the one incident for which he had applied for amnesty, he was never, in his 40 years of police service, involved in executing a criminal offence. And he was firm in his recollection that at no stage of his apartheid-era career did he receive training in interrogation or torture methods.

This is contrary to Erasmus’ testimony from last year that security officers attended a training course led by Brigadier Neels du Plooy in which they were taught methods of torture, including assault and psychological torture techniques.

Naude said he took the same course as Erasmus and that no such training took place.

Related article:

It was this insistence by Naude that led the inquest down a fascinating and dark, if somewhat out of the way, path.

To address Naude’s repeated commitment to his image as a law-abiding member of a recognisably brutal regime, and thereby cast doubt on his overall credibility, Varney requested to introduce a series of new documents.

Naude’s legal team objected, questioning the relevance of documents related to his career after his involvement with Aggett and concerned they would touch on allegations made at the TRC, which Naude had not been asked to answer at the time. But Makume ruled that the material could be offered into evidence in light of the question over Naude’s credibility as a witness.

These documents are in the public record and deal with Naude’s work as a member and later commander of C2. What Naude had to say about them, while not necessarily contradicting his version of events in the Aggett case, does provide a revealing glimpse into the minds of former members of the apartheid security forces. It shows the many twisted turns of thinking they employed to justify their firmly held and often proffered belief that they were merely doing their jobs.

C2 and the Terrorist Album

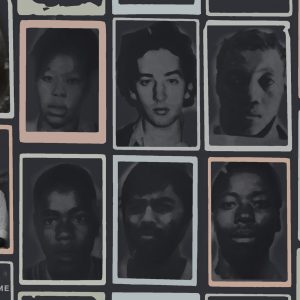

C2 was responsible for information on political exiles and perceived threats to state security under apartheid. One of the main tasks of Naude and his colleagues was the maintenance, updating and distribution of a collection of several thousand mugshots of anti-apartheid activists and exiles known colloquially as the Terrorist Album. The security police, in particular members of Vlakplaas such as Eugene de Kock, used it to put faces to the names of targets the government selected for harassment and elimination.

Vlakplaas and other similar units became – in the late 1980s and following the public and increasingly vocal outcry against deaths in detention in apartheid prisons and police stations, like that of Aggett in John Vorster Square – the main means by which the apartheid state waged war against its enemies.

These units, carefully protected and located far from public scrutiny, were allowed to operate with almost total impunity. They carried out actions that, while certainly against the laws of the country at the time, were sanctioned and protected by the state and its leaders.

As author Jacob Dlamini shows in The Terrorist Album, there was a “relationship between the album and death. Policeman Craig Williamson killed Ruth First for no better reason than that she was in the album … To be on its pages was to be marked for death. As Williamson said, echoing the hunting metaphor beloved by the police, to be in the album was to be fair game.”

Related podcast:

Naude would undoubtedly have been aware of how the information he handed to his friend “Gene” de Kock was used and what the consequences for its targets would be. When pressed by Varney, Naude insisted that while he had no problem answering questions about his work for C2, he was “not directly involved in any killing of anybody. I was just the instrument for the collection of information. I had a job to perform. If we are going to enter everyone’s name into the system [the TRC database], thousands would be here in my situation.”

He failed to acknowledge that the actions resulting from his work could be defined as criminal – even though they often included kidnapping, torture, disappearances and death – saying that in his understanding of the conditions of war he and other members of the security forces were told they operated under, “My definition [of a crime] is not the same, unfortunately.”

He added that if Varney and others wanted to define these actions as crimes and prosecute those responsible, then they “should start with [former state president] PW Botha”.

Related article:

Naude said the functions of C2 had been determined within a bureaucratic organisational structure that he had nothing to do with creating and had no ability to change. When asked by Varney if he felt De Kock had been hung out to dry by his superiors to protect themselves from investigation by the TRC, Naude said that he did. “They never stood up for Gene. Gene is a very capable and able person, but he was left alone.” He added, “In my world [the world of former security police officers], these questions are still the order of the day.”

Naude also made a comment about his C2 work that may appear no more than a throwaway, but it points to the broader issue that has been plaguing the commitment to prosecute TRC-related cases over the past two decades. When asked if he conducted interrogations as part of his work, and after clarifying the genteel nature of these interrogations, Naude told Varney, “I was personally involved in many interrogations by C2 … If I was to testify as to everyone I’ve interrogated during my eight years there, people would be surprised.”

Naude appeared to be hinting at having information about informers in the liberation movements in whose interrogations he was involved, adding grist to a long-held whisper of the political rumour mill that one of the key impediments to the successful prosecution of post-TRC cases is the threat by former perpetrators of apartheid-era violations that were they to be prosecuted, they would retaliate by revealing the names of those who gave them information.

Related article:

It is not within the mandate of Makume’s inquest to prosecute Naude or hold him to account for the work he did as a member of C2. But his evidence regarding that part of his career may cause the judge to question whether or not Naude could reasonably believe that Aggett was simply an unfortunate victim of circumstance who had no part to play in Cronwright’s imagined trial of the century, or if as long as Aggett and Naude chatted and smoked and compiled their statement, he had nothing to fear from other members of the Security Branch.

For Naude to believe otherwise and accept that his seemingly gentle participation in Aggett’s interrogation was complicity in his death and not just part of the job appears to be too much to expect. After all, those who signed the orders for the trains to transport prisoners to Auschwitz and who helped develop cars that could be used as portable gas chambers weren’t killers, they were merely doing their jobs.

The Aggett Inquest proceedings are streamed live on the Facebook page of the Foundation for Human Rights.