Long Read | Simon Gush’s art is labour as concept

The artist’s new exhibition at the Stevenson gallery continues his enquiry into the meaning and realities of labour, drawing on Mexican muralism and progressive theory.

Author:

15 November 2021

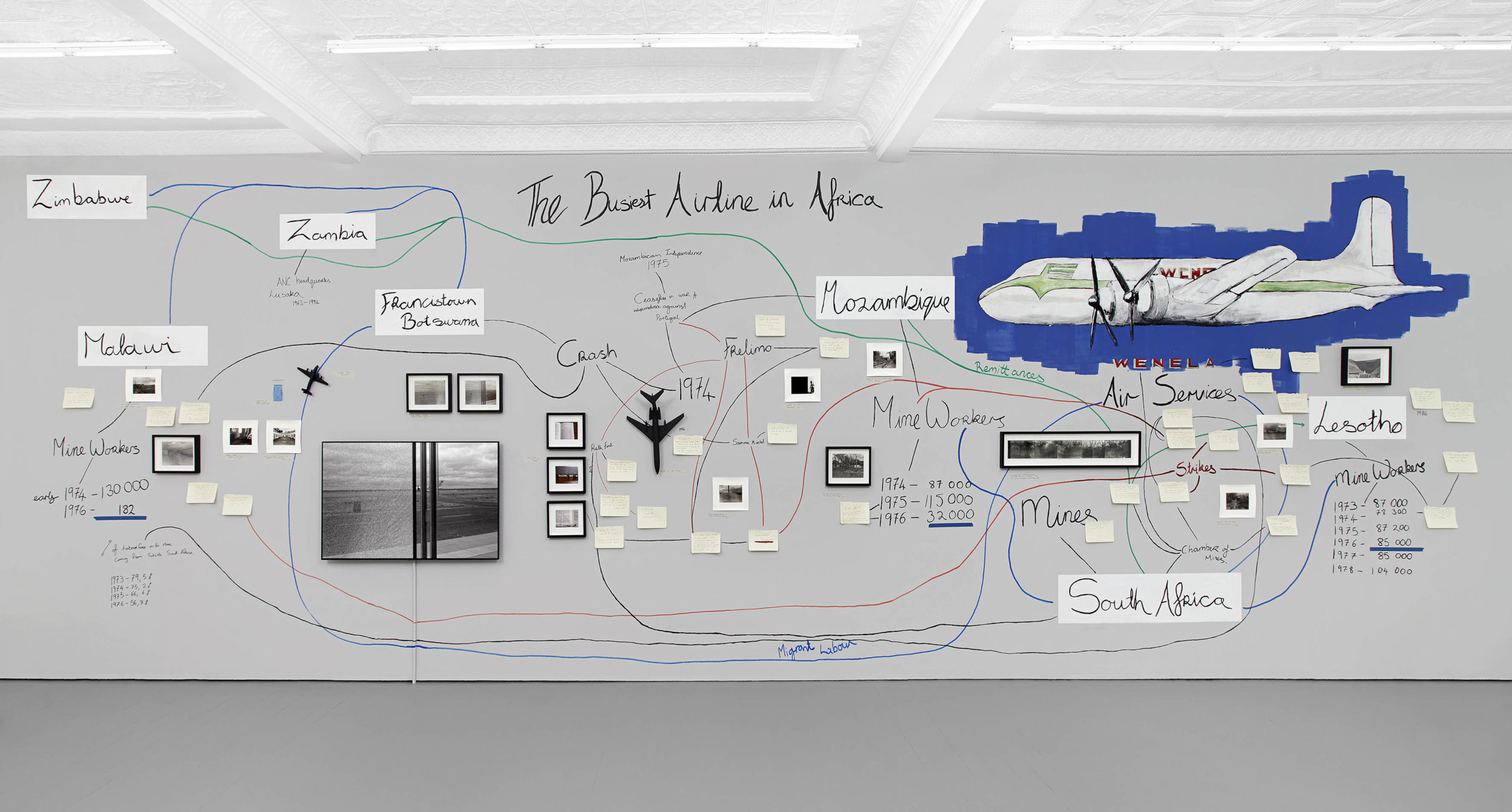

For a time, Wenela Air Services (WAS) was reportedly the busiest airline in Africa, its cargo of human labour – hundreds of thousands of miners – being transported to South Africa’s mines in overcrowded and unsafe planes flown by cowboy pilots.

Formed in 1952 and based in Francistown, Malawi, it was operated on behalf of the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association (WNLA), a labour broker organisation that still exists today, in a different guise, as Teba Recruitment. The airline flew thousands of migrant labourers from Malawi, Zambia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia and Lesotho, inserting the aeroplane into a popular imagination that has, historically, centred on the steam train.

Related article:

In his latest exhibition, The Busiest Airline in Africa, artist Simon Gush, 40, continues his career-long enquiries into waged labour, the nature of work, migrancy, the separation of work from home and the diminishment of the work of living and sustaining life – all of which draws from a theoretical foundation that spans Karl Marx, Silvia Federici and others.

The exhibition, which includes an in-gallery occupation by Gush and various collaborators that led to the creation of a mural and a series of live events, focuses on the history of WAS and its part in the tentacular machinations and influence of South African imperialism and capitalism in the region.

Screened alongside the exhibition are two films made during the coronavirus pandemic lockdown – SG, 59 Joubert Street, Johannesburg and On the Horizon of a Blue House by the Sea – which are more personal and inward-looking in their reflection on isolation, intimacy, work and uncertainty.

Niren Tolsi: Your enquiries have been embedded in notions of work, migrant labour, the separation of work and home, and so on. What has shaped this pursuit and sustained this curiosity?

Simon Gush: Once I started asking questions about work, I very quickly found myself obsessed with trying to understand the complexities of what it is, what it means, why it is so central to how we think of ourselves, our identities, subjectivity, and how it determines our place in society. Figuring some of this out seems especially important in a country where so few people have access to waged labour. The production, reproduction and control of work and workers is a through line in our history and important to understanding many key issues, including land dispossession and restitution. In my artwork and research, I have been asking these questions for over 10 years and I still feel like I need to know more and understand it better.

My work has taken me into looking at the history of trade unionism in South Africa, the ideological construction of work through colonialism and Afrikaner Calvinism, and importantly, the defining role of migration. I am interested in migration, not only as the actual condition of many workers in southern Africa, but as the basis for how we understand waged labour: the physical manifestation of the capitalist separation of work – “productive” work or waged labour – from the home’s “reproductive” work or unwaged labour.

Tolsi: How did this project come about? Can you describe the various stages of the process until it entered the gallery?

Gush: The project started in 2015 when I was reading Ruth First’s book Black Gold. There were references to the WAS crash, the resultant withdrawal of Malawian mineworkers from South Africa, and Mozambique partially filling this gap around the time of its independence from the Portuguese. I was intrigued not only by discovering the existence of WAS, which itself shifts a centrality of the narrative of the train, but that the effects of the crash rippled out across the region, particularly as South Africa began to shift its policies to foreign labour.

Just this quote from the interdepartmental committee of inquiry into riots on the mines in the Republic of South Africa in 1975 seems so telling: “… in certain cases the attitude of Mozambicans towards management and whites was influenced by Frelimo successes in Mozambique”. This was not a story just about a terrible airline driven by profit and technology, but about the shifting power of South Africa exercised through migrant labour and remittances, and the impact of the success of the independence movements on the economic stability of labour in South Africa. But I only realised this later this year when I came back to the project with a different view. At first I was thinking only of the story of two crashes: the WAS crash in 1974 and the crash that killed Mozambican president Samora Machel in 1986.

Related article:

In 2016, I visited Francistown to do initial research, speak to a few people who remember the airline and visit the disused WAS compound there, but it didn’t feel like enough. Then, returning on the flight to South Africa, the film containing the photos I had taken went through the X-ray machine and was damaged. Also, most of what I had videoed was out of focus as I was trying to work a new camera. At the time I was dejected. There were so many gaps, it was hard to find information, the footage seemed useless and I didn’t know what to do, so I shelved the project.

The last two years of lockdown and being unable to go out to do new research meant that I was thinking and talking about old unfinished projects. A conversation with a friend about this sparked my interest again. I began to think about how to work with gaps, with the uncertainty. I wanted to see if I could use what I knew and draw out the connections that were already appearing.

The story was worth telling. It is not an authoritative version. There is space for others to expand on it. Making the mural over time in the gallery rather than planning and then executing it for an opening allowed me to find more connections, think differently about it and realise that, even for me, it is not finished – that I can keep growing, remaking and developing this work beyond this exhibition. I might not fill all the gaps, but I have had to learn to live with uncertainty.

Tolsi: You have noted that it was important for the exhibition to “take place in time rather than just space”. How have you achieved this and why was it important to do so?

Gush: When I start thinking about an exhibition, my imagination is often determined by the space. I think about what I want to do and how to piece together, conceptually and physically, a show. But when I began planning this exhibition late last year, we were in the second wave [of Covid-19] and I had no sense of what the situation would be when I finally got to make the show. It didn’t seem to make sense to make an exhibition, open it and no one came to see it.

So I began to think instead of a space that I would have for an exhibition, maybe what the gallery was offering was time. For six weeks I could do some work, develop my ideas and let the exhibition unfold in another way. In the end I was lucky that the timing was good and I could share the process with friends, collaborators and even an audience.

It is hard for me to show work unfinished, in process, but I think it strangely gave the physicality of the show a different weight. For those who wanted to come and engage in the talks and musical performance, the ongoing evolution of the mural was a way to re-engage with space, but over time.

Tolsi: The in-gallery “occupation” included various collaborations and the creation of a mural that was influenced by Mexican muralist paintings. Why the collaborations? What effect did they have on your work?

My work is always in conversation and collaboration with others. During this exhibition, I invited a number of people who are essential to my thinking to be part of the public programme: director of the Society, Work and Politics Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) Prishani Naidoo, Wits University sociology professor Bridget Kenny, and sound artist and musician Andrei van Wyk, who performed with Daniel Gray and artist Dorothee Kreutzfeldt. Bridget and Dorothee also collaborated on ideas and came to paint with me in the space. Andrei created the scores for the films, which are a key part of their aesthetic.

Probably the most important collaboration, however, was with Mexican artist and intellectual Helena Chávez Mac Gregor. The film we made together, On the Horizon of a Blue House by the Sea, comes out of a conversation over the last couple of years about work and life. Helena has been working on projects about the work of maternity, of mothering, and together we worked and talked about the work of love, intimacy and of life. All of the show is indebted to those conversations.

Tolsi: Why the interest in Mexican muralism?

Gush: I have a long-standing interest in muralism, particularly because of the history of the representation of workers and work in the medium. During a trip to Mexico in 2018, I started to really engage with the tradition there, which is quite different from the Soviet-influenced iconography of work that is more common, especially among the trade unions, here.

Diego Rivera’s murals are really special when you physically encounter them. There is a surprising softness. During my last trip in January, I realised that his compositional use of the multiple narratives across the picture plane was a solution for what I was trying to do. My work is not a mural in a traditional sense. It uses a kind of diagrammatic mapping of the ideas, events and histories represented and is combined with notes, paintings, photos and a short film. But even that mapping has some precedent in his work Modern Industry [part of the Detroit Industry frescoes, 1933], which visualises through interconnecting pipes the relationship of work, power and economics in a way that is not dissimilar to what I tried to do.

Tolsi: The exhibition’s various components are both outward-looking and very personal and introspective. Please comment.

Gush: In the first room are the two films which are very inward-looking – On the Horizon of a Blue House by the Sea and SG, 59 Joubert Street – in which I try to ask the questions of work to myself first before I am prepared to ask them of anyone else.

But even in The Busiest Airline in Africa room with the mural where I engage with the impact of Wenela and the way in which work is wielded as a proxy for power in the region by South Africa, I would argue that to engage with the effects of work in the region doesn’t require me to look far.

Maputo is 550km away from Johannesburg and Maseru is 420km, while Cape Town is 1 400km. Most of us living in Johannesburg are interacting with migrants every day. It is an essential part of the society we live in. To understand anything about this city, this country and especially to understand anything about work, stopping at the borders makes no sense. Our borders are porous and that porosity is historical.

But, saying that, borders do have effects. A coincidence I realised only when making the mural is that on 19 October 1986 South Africa allegedly caused the crash of Machel’s plane and five days later, on 24 October, the apartheid government signed the treaty on the Lesotho Highlands Water Project: two different exercises of power in the region. The 1998 invasion of Lesotho and the bombing of the Lesotho Defence Force base at Katse Dam, essentially the securing of the continued flow of water to the Witwatersrand, is a result of the continued exercise of this power. The popular dismissal of this – that it was when Mangosuthu Buthelezi was acting president – is belied by the extended occupation of Lesotho after the invasion and that South Africa renegotiated the terms of the treaty to favour it even further during this time.

I think it is both the fact that we don’t like to take account of the power we wield in the region, but also that we love to romanticise Nelson Mandela’s presidency, that this occupation and treaty renegotiation linger in the popular imagination mainly as an aberration and source of humour.

Tolsi: The separation of work and home is essential to your intellectual and artistic enquiries. Did the pandemic lockdowns change how you approached your practice on a personal and intellectual level, and how so? Has it changed anything for ordinary workers in South Africa?

Gush: Marx points to this problem of the separation of productive and reproductive labour, home and work in Capital, but really doesn’t develop these ideas sufficiently. It is Marxist feminist thinkers such as Silvia Federici who really start to develop this analysis in conversation with another key Marxist concept: primitive accumulation, or the enclosure of the commons and land dispossession. These ideas are really important to me. There is a tradition here, for example, the late Marxist sociologist Harold Wolpe looks at the reproduction of the labour force, but there is a lot of work still to be done.

Increasingly, I am interested in thinking about work in a way that acknowledges the unpaid work – cooking, cleaning, raising kids, caring for the elderly, etc – that makes waged labour possible without reproducing this capitalist separation in my analysis. I’m trying to conceive of work as a network of the exchange of labour across households, families and communities, where the precarity is often shared, rather than thinking through an individual’s relation to employment.

Related article:

The basic concept of this separation is something like the dispossession of land and breakdown of the possibility of subsistence. It means to survive, families would have to turn to the wage. Generally, the man would have to go find productive, paid work and the woman would stay home to perform the reproductive, unpaid work: a physical separation of the sites of work. But the pandemic and the collapse of home and work of course does mean some sort of integration. The separation is not just physical but ideological and part of a gendered and racialised system of value.

The pandemic really exaggerated these problems. The experience of the lockdown for most workers was probably the loss of work altogether. For those that could work from home, a lot depended on how good their job was and, as such, how much space they had to work in and what share of the reproduction of labour they participated in. I’m possibly essentialising it a bit: if you are a rich white man who shirks your share of the work at home, lockdown was probably okay. For most people, however, I think it made more visible the problems already inherent in the system of work.

Tolsi: The exhibition reveals points of staggering irony. The WNLA/Wenela eventually becomes Teba recruitment, whose chief executive is James Mohlatsi, the first president of the National Union of Mineworkers. This illuminates contradictions about post-apartheid South Africa and the nature of capitalism…

Gush: I am not sure if this will completely answer your question, but something that appears very revealing to me about the problem can be found on the Teba website. In its About Us section, there is a very brief history of the organisation, exceedingly brief and celebratory. There is no mention of the original name, the Witwatersrand Native Labour Association, a name that is despised throughout the region. Included in the timeline are dates during apartheid but no mention of apartheid. Of course, most companies don’t want to advertise their negative histories, but how is it possible that the company thinks it could transform from one of the most hated to something valuable if it erases its history – a history entangled with coercion, oppression, silicosis, criminally low wages and abuse.

Each website section has an image in the header of a happy or content-looking worker. In the Employee Services tab, a group of miners smile for the camera underground, but to the right one worker stands apart and seems to be rolling his eyes and gazing off into the distance. I am with that guy.

Tolsi: South African narratives around labour have been about job creation. Is this outdated and should we be thinking differently about the notion of work?

Gush: In a corner of the mural, I break down the most recent labour force stats. Unemployment is at record highs; if we look at expanded unemployment it is even more scary. But possibly the most revealing stat is the absorption rate – what percentage of the total working age population has employment, defined as one hour of paid work in the past seven days – of 37.7%, just more than a third of that population. Most South Africans will never experience waged work. To think that we can have the kind of economic growth that will allow for full employment is a pipe dream, especially if we follow the current logic of the government that somehow these jobs might emerge from the private sector. In reality, unemployment has been historically structured into our economy. Simply put, the problem of work cannot be solved by jobs. We need different ways of approaching the problem.

This is where I think the conversation around a universal basic income is really important. I believe we need a radical campaign around this. It can’t be conceived of as something that will work with the current system of work. It needs to be an alternative to work, making work a choice, not a necessity, something that reflects both that there will never be enough waged work for everyone and that unpaid work is constantly being performed and should be paid for. We need to demand a universal basic income of R12 500 a month, an amount that is both symbolically important because of Marikana, but also a real living wage.

The Busiest Airline in Africa is on at the Stevenson gallery in Johannesburg until 19 November.