Long Read | George Bizos’ strength of an elephant

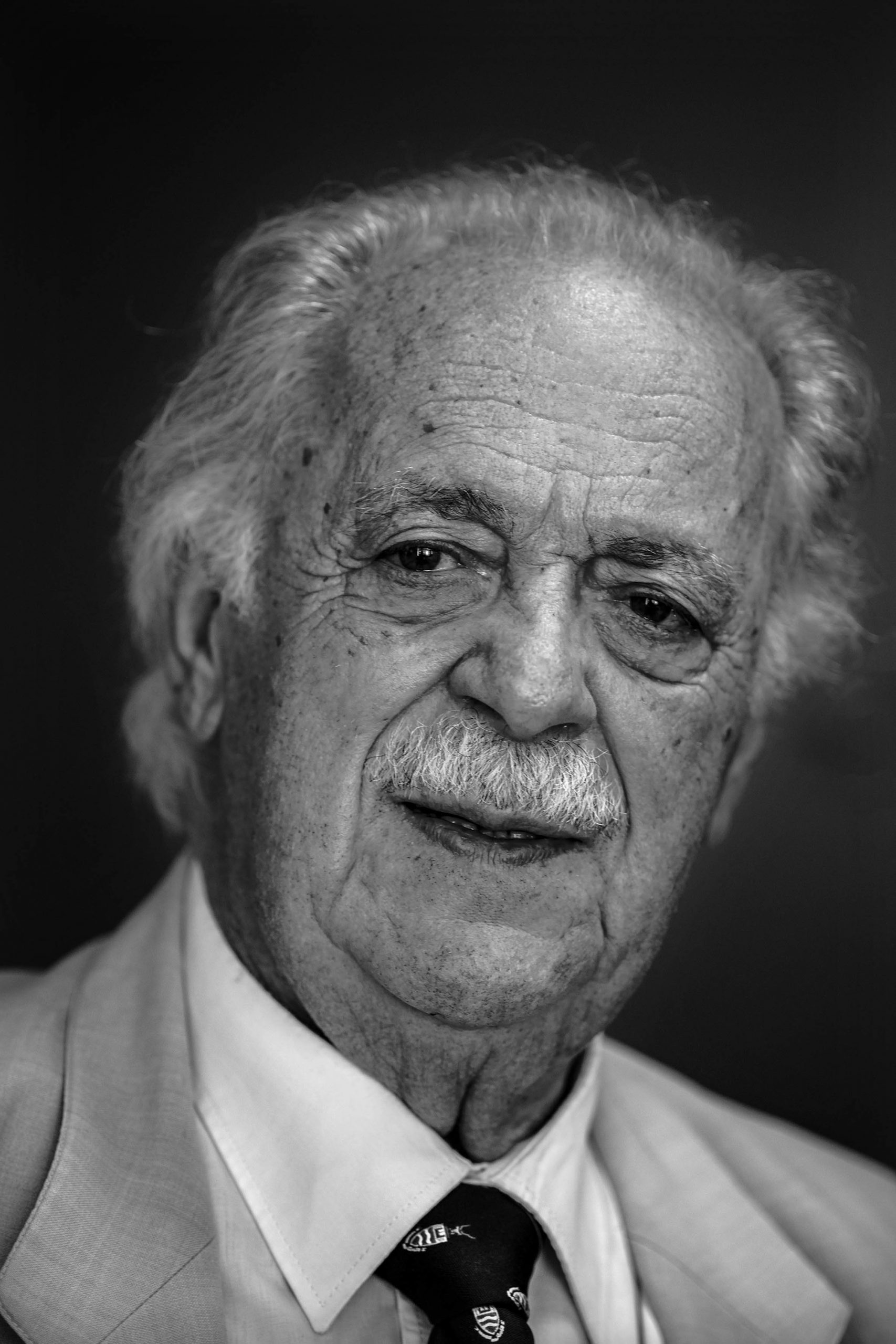

With the renowned advocate’s death on 9 September, South Africa has lost a man of immense morality and a tireless campaigner for the downtrodden and the traumatised.

Author:

11 September 2020

The death of George Bizos, the human rights lawyer and indefatigable prosecutor of apartheid’s white supremacy and its brutal orchestrators and defenders, sent tremors throughout a South Africa floundering in a crisis of identity.

During a Covid-19 pandemic that has laid bare a 26-year-old democracy’s failures, Bizos’ death confirmed one of the final breaks between a generation of freedom fighters and anti-apartheid activists who emerged in the 1950s and 1960s and a contemporary South Africa in which harsh inequality driven by the rapacity of the political and corporate elite, corruption, kleptocracy, embedded racism, state violence against a perpetually marginalised black community and its resultant trauma, and a virulent emerging fascism run deep.

Bizos died of natural causes after his health deteriorated with old age. He was 92 years old. As long as he drew breath, he lent his lawyering skills and his gargantuan moral authority to the attainment of what Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko described as “a position to bestow on South Africa the greatest possible gift, a more human face”.

Related article:

It was Bizos’ humanity that drove him to pursue the truth in seemingly futile inquest after inquest into the suspicious deaths in police detention of activists such as Biko, Neil Aggett, Ahmed Timol and others, despite the crushing inevitability of apartheid’s magistrates finding “no one to blame”.

He wrote of this series of injustices in the book No One to Blame? In Pursuit of Justice in South Africa. In the foreword to the book, Bizos’ friend and writer Nadine Gordimer described him as a “South African civil rights lawyer of international standing, a devastating cross-examiner of apartheid’s authorised torturers and killers … When George Bizos won a case, it was not just a professional victory, it was an imperative of a man whose deep humanity directs his life.”

Fearsome reputation as a lawyer

A close friend of South Africa’s first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela, who he represented at the 1963 Rivonia Treason Trial, and its first chief justice, Arthur Chaskalson, who was also part of that legal team, Bizos developed a fearsome reputation as a trial lawyer whose superior cross-examination skills were founded on an instinctive sense of people and a burning rage against injustice.

Such were his skills that Bizos’ reputation as a lawyer extended beyond the borders of South Africa and into the ANC guerrilla camps in Angola and Zambia. In a 2008 interview with the Oral History Project of the Legal Resources Centre (LRC), Bizos remembered, with a laugh, meeting South African Communist Party (SACP) and Umkhonto weSizwe leader Chris Hani in 1987: “On my second trip to Lusaka, he told me that part of the training of the comrades was, ‘If you’re caught, ask for Bizos.’”

Related article:

Bizos was a migrant whose arrival in South Africa as a 13-year-old is, in itself, a tale of daring and democratic impulses. Coming from an “anti-tyrannical family who didn’t take kindly to dictators”, his father Antoni was the mayor of a small Greek village who had been defrocked following the country’s occupation by Nazi Germany.

Seven Allied troops from New Zealand, Australia and England were hiding on the outskirts of the village, and Antoni decided to help them get out of Greece to safety in Crete in a rowing boat. Unbeknown to them, Crete was also falling to a German invasion at the time. A “precocious” Bizos insisted on accompanying his father on this 1941 odyssey that would lead to them being picked up by the British Royal Navy, taken to Egypt and, finally, dropped off in Durban before being resettled in Johannesburg.

Early radicalisation

Bizos took up political cases soon after he qualified as a lawyer from the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). This led to his being constantly denied citizenship and a passport by the apartheid regime, a consequence of which was that he would only see his mother again 21 years after he left her, during her visit to South Africa in 1962.

In a 2012 interview, Bizos told me he had been “radicalised” at Wits, where he met the likes of Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Ismail Meer and Nthato Motlana. Members of the university’s Student Representative Council (SRC), to which Bizos was elected, and its student body had participated in the war, and many were anti-fascist and anti-Nazi. This resulted in an open hostility to the pro-Nazi Nationalist Party, which swept to power in 1948.

An SRC objection to the quota system that limited the number of black students admitted to medical school at Wits included an unashamed criticism by Bizos. It made newspaper headlines and caused future prime minister DF Malan to incite right-wing students on campus to overthrow the student leadership.

Related article:

Bizos joined the Johannesburg Bar in 1954 and for the rest of his career he represented victims of apartheid violations. He was conferred silk in 1978 and was made an honorary life member of the Johannesburg Bar in 2004.

He campaigned for lawyer Duma Nokwe, whom he knew from university, to be admitted as the first African to the Bar, despite strong resistance from conservatives in the establishment. When it seemed that Nokwe would not be able to find white junior counsel to share chambers with – which would have prevented his successful acceptance to the Bar – Bizos offered to share his.

Drawn to political cases

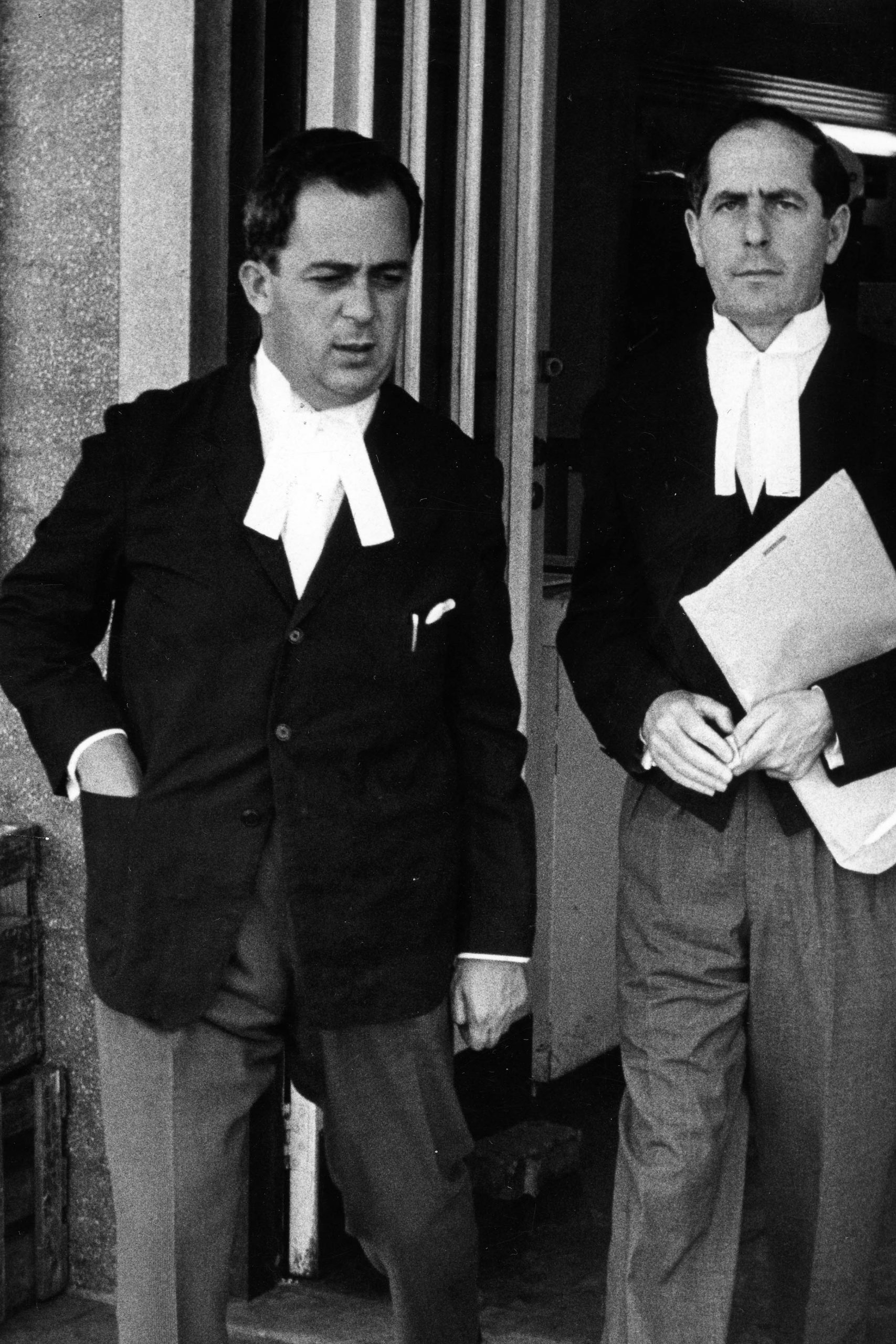

Bizos was friendly with political troublemakers like Mandela, Ruth First and Joe Slovo. He served as counsel for Mandela, Govan Mbeki and Walter Sisulu at the Rivonia Treason Trial with a team led by Bram Fischer that included Chaskalson, Vernon Berrangé and Joel Joffe. According to Stephen Ellmann’s biography of the late chief justice, Arthur Chaskalson: A Life Dedicated to Justice For All, the trial “cemented” lifelong friendships between these lawyers.

With the deaths earlier this year of the last remaining accused, Andrew Mlangeni and Denis Goldberg, Bizos’ death marks South Africa’s final break with that seminal case.

Related article:

As Bizos told the LRC Oral History Project: “The government thought that it had struck a death blow to the struggle. It turned out … to be wrong because the 10 accused that were charged, particularly Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Rusty Bernstein, turned the trial around. The accused became the accusers. They said yes, we may have transgressed the man-made laws, but we were not obliged, because of the lack of legitimacy, to obey them. We went into violence but with a caveat that we would try our best to avoid the loss of human life…

“And what happened was the Nelson [Mandela] statement, Walter Sisulu’s evidence; they actually got across what the grievances of the oppressed people of the country were.”

Related article:

Bizos was credited for having persuaded Mandela to add the phrase “if needs be” in the latter’s famous “I am prepared to die” speech on the witness stand before sentencing in the Rivonia Trial. There were concerns that the trialists would be sentenced to death and that Mandela’s speech would appear to be an invitation for such a sentencing.

The result was a subtle, but important distinction: “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die,” Mandela said.

“I suppose those words are my contribution to the struggle,” Bizos humbly submitted in an interview.

Unwavering dedication

South Africans would believe otherwise. Bizos was a consistent thorn in the side of a racist and oppressive regime. The 1970s and 1980s brought with it increasing political activism countered by ramped-up state repression. Detention without trial became a repressive norm in South Africa, and likewise, the prevalence of suspicious deaths in detention.

Between 1963 and 1990, 73 detainees are known to have died in police detention. Bizos, with lawyers like Issy Maisels and Sydney Kentridge, would tirelessly pursue answers, justice and closure for the families of many of the activists who would be tortured and murdered by the Security Branch police.

“He stayed the course and ran inquest after inquest, all unsuccessful [because of pro-regime magistrates]. There was no justice delivered, no prosecutions and he had to be with the traumatised families of murdered activists, and yet he never wavered,” said Jason Brickhill, a former head of the LRC’s constitutional litigation department, who Bizos mentored from 2008.

Related article:

One of Bizos’ last appearances in court came in the witness stand when the inquest into the death of SACP activist Timol was reopened in 2017. Timol’s death in 1971 was the first in detention at the notorious John Vorster Square police station in Johannesburg. Others, such as those of medical doctor and trade union organiser Aggett and the horrific death of Biko, would follow.

In the witness stand in courtroom GC in the Johannesburg high court, Bizos spoke in a voice just louder than a whisper but with a deafening moral authority. He described a justice system in which security police “controlled magistrates and prosecutors” and would “manufacture false evidence”, and told of state doctors who violated their Hippocratic oath by fabricating forensic evidence.

In testimony that was laced with humour and indignation, Bizos unpicked every failure and miscarriage of justice by the state pathologist, the police and the magistrate. It exposed the police version that Timol had fallen – and not been pushed – from the 10th floor of John Vorster Square as a barefaced lie. Judge Billy Mothle, in a historic judgment that has triggered a renewed search for the truth for the families of murdered activists, would find that Timol had indeed been thrown to his death. Murdered.

Long road of political trials

Bizos and Chaskalson were a masterful double act in and out of the courtroom. LRC attorney Clive Plasket remembers in Ellmann’s biography of Chaskalson “that it was quite disconcerting for the rest of the team that Arthur and George, schooled in discretion by years of political cases, spoke in a kind of code so as not to be successfully overheard by the police – but their code was so effective that they were quite unintelligible even to their colleagues”.

At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), Bizos would again represent the families of activists like Biko, Matthew Goniwe of the Cradock Four and Hani. He would argue vociferously against the granting of amnesty to people such as notorious Security Branch member Eugene de Kock and others.

“This was very important work that was done,” Bizos told the LRC Oral History Project, “because whatever blemishes there may have been in the TRC, it serves what the records of the Nuremberg trials do.”

An imperfect justice

Responding to Ellmann’s observation at the time of the TRC that Bizos “didn’t like amnesty”, Bizos admitted that was true. “But I have always justified it on the basis that had it not been this compromise during the negotiation stage, there may not have been a settlement, of course. The senior police officer threatened during the negotiations that unless there was provision for amnesty, the ‘manne’ would not accept a settlement. And it’s true that it’s not perfect justice; it may not be even justice. But how much more injustice would there have been if we had a race war? And how many innocent people would have died in that conflict?”

In a demonstration of Lady Justice’s deliciously ironic sense of humour, Bizos and Mohamed Navsa, then an LRC lawyer, now a distinguished judge of the Supreme Court of Appeal, helped draft the Amnesty Act, more especially Section 20, which covered the grounds on which amnesty could be granted or refused.

The 1980s had heralded the emergence of daily civic activism and protest under the banner of the United Democratic Front (UDF). This was countered by apartheid death squads, the disappearance of activists, putting the army on the streets of the country’s urban centres and the state-funded Inkatha wreaking bloody violence in KwaZulu-Natal during a period that included two states of emergency in 1985 and 1986.

Related article:

There were two major treason trials at the time. One in Pietermaritzburg involved UDF leaders such as president Archie Gumede, treasurer Mewa Ramgobin, Natal Indian Congress president George Sewpersadh, Albertina Sisulu and others. The second, the Delmas Treason Trial, started in 1985 and finally ended in December 1989 with the 22 accused, which included Mosiuoa “Terror” Lekota, Popo Molefe and Gcina Malindi, finally being acquitted. Such was the ferocious, booming power of Bizos’ courtroom exploits that Lekota conferred upon him the nickname Matla a Tlou, one with the strength of an elephant.

Bizos joined the LRC as in-house counsel in its constitutional litigation department in 1991 after becoming “a little disillusioned with private practice, because people with a lot of money thought that … you can be the gladiator whether there was justice in their case or not”. At the public interest law firm, he would take up the fight for the downtrodden and marginalised with renewed vigour, while still reserving 30% of his time to pursue cases independently.

End of the death penalty

The advent of South Africa’s constitutional dispensation allowed the potential for a new justice to entrench itself in South Africa, one based on equality and dignity for all.

Bizos argued one of the Constitutional Court’s seminal early cases, S vs Makwanyane and Another, which saw the court outlaw the death penalty. “We persuaded the court that the Constitution couldn’t be interpreted in any other way and [the death penalty] was a cruel punishment. And it’s an important landmark in world jurisprudence because all 11 judges gave judgments, and there were different aspects of it, and you know, it was one of the most important cases at that time in my life, I think,” he told the LRC Oral History Project.

In 2012, mere months after the police murdered 34 striking mineworkers at multinational company Lonmin’s platinum mining operation in Marikana in North West province, Bizos stood up in a municipal hall in Rustenburg at the beginning of the commission of inquiry chaired by retired appeal court judge Ian Farlam.

At that point there was still squabbling and confusion between various public interest law firms as to who represented which clients. Bizos would stand up and proclaim: “I represent the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa.” No other lawyer would have been able to carry off such an announcement, only someone of Bizos’ moral heft, immaculate credentials and mischievous sense of humour.

Related article:

Bizos and the LRC would eventually represent the South African Human Rights Commission and the family of Papi Ledingoane, one of the killed mineworkers. During a 2012 interview, Bizos told me that he believed Marikana was a watershed moment in post-apartheid South Africa and the violation of human rights – murder and alleged torture – that occurred there “saddened” him.

“This is a matter of concern for me because I have been at it [taking up social justice and human rights briefs] since 1954, and I never thought I would be called upon to represent people whose rights have been violated, what is it, 50 to 60 years later. I am saddened by it,” he said.

He had hoped that the Constitution he helped to draft would have guided the government and the police in all their actions at Marikana and beyond. Unfortunately, this was not the case.

Vital role at Marikana inquiry

But all Bizos’ experience in fighting apartheid-era police, what he described as “nous”, was brought to bear in the LRC’s work at the commission. These included the vital protection of evidence in the days following the massacre and the commissioning of independent forensic pathologist reports. They countered those of the state and provided damning evidence of wounds and bullet trajectories that confirmed the murder of mineworkers – especially at “scene two” where, based on these reports, it was established that the police had hunted down and killed mineworkers who posed no threat to them.

In a 2013 public address titled “Mandela’s Trials and Tribulations”, Bizos said of his friend: “With undue humility, he disavows that he was the great leader that brought democracy, freedom, equality and dignity to the people of South Africa. His concern about the nation, his family, his friends and even those whom some would consider his enemies makes him a great world leader.

“The lives of all of us who have crossed his path have been enriched. Had it not been for his optimism and leadership, many of us may have given up,” he added. “It will be hard to find another South African leader to follow him.”

Much the same can be said of George Bizos, a migrant to this country, a singular South African whose search for justice was driven by a deep humanity and an unflinching quest to heal a traumatised country until his final breath.