Long Read | Frida Kahlo: A ribbon around a bomb

In this extract from her recent lecture at the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation, Helena Chávez Mac Gregor reckons with the memory and place of Frida Kahlo in our contemporary imagination.

Author:

27 June 2022

Writing about Frida Kahlo is difficult. So much has been said, her work has been examined in the light of her letters, her house, her clothes, her personal belongings, her relationships, her suffering. What else can be said?

I am part of a generation that watched her become a celebrity, a condition in which she stopped being Frida Kahlo and simply became Frida. The movement, which emerged in the 1980s and gained unprecedented force in the 1990s, not only aimed to make visible the work of a female artist who was already dead – as was the case of María Izquierdo or Leonora Carrington – but also to transform her into a kind of symbol. A symbol of what, I am still not sure. A symbol of fashion, a country, an identity, an economy.

We saw how, while the country’s dreams of social justice collapsed, she was exoticised. Her work, both material and the rights, is safeguarded by Mexico’s central bank, Banco de México, by a trust created by Diego Rivera before his death. Her image, the image of her own self, her persona or whatever resembling it, is safeguarded by the Frida Kahlo Corporation managed and monetised by what is left of her family.

My mother lives on the street where the Casa Azul Museum is located, in the traditional neighbourhood of Coyoacán, south of Mexico City. Every day I see hundreds of people lining up to get in. Many, in fact, are satisfied with taking selfies at the door of the house where the painter lived from her birth in 1907 until her death in 1954. My daughter, who is now five and has grown up in museums while I set on exhibitions and her father exhibits his pieces, the only artist she recognises is “Frida”. She recognises her on T-shirts, dolls, television commercials. She identifies her face; the artwork slips from her. She can’t tell whether she likes it or not.

There is so much in sight that, I realise, it slips from me too. I wonder why is it that in order to value Frida Kahlo’s work, her life has been scrutinised? Why has it been interpreted from her biography? From an interpretative psychology yearning to find, in each shape, stroke and colour, the key not only for her work but for herself; as if there were a hidden secret that we have to decipher in order to grant dignity to a work and a life. Has any male artist been subjected to this treatment?

Undoubtedly, the fact that her body of work is mostly self-portrait has “authorised” the idea that her work is a way of introducing herself, and therefore we can and must reveal her, find what she represents, as the other part of the symbol that she sustains and signifies. Under the dynamics of celebrity, commodity and complete transparency, some of her work’s political powers and readings have disappeared.

I confess, in the face of saturation, I could see nothing. There was the obvious and I wasn’t interested in looking at it or to see if I could find something else. It was this invitation, coming to speak here in Johannesburg, that forced me to look, and I found a world.

As Roland Barthes decreed long ago, my generation was also formed by the death of the author. This does not mean that the contexts of production and life do not matter; on the contrary, as Foucault would later show, there is no way of understanding either words or things without the historical conditions that open them up. This principle does mean that seeking the meaning of an action or production from the intention of a founding consciousness is a false problem. What Frida Kahlo was – what she wanted, thought, desired – is, fortunately, beyond my reach. What I have at hand is the work, the texts, the critical possibilities existing in her work. The work is not an absolute category either, but rather a device open to different interpretations and readings, hence the importance of not fixing it in the author.

What I am interested in doing here with you is to be able to understand the body, or a certain body, of her work; to analyse what it opens up, from where, towards what it is directed. What I can do is try to interpret the work in the light of my own interests, which in recent years have revolved around feminism and motherhood, and from there, try to see beyond Frida, the art of Frida Kahlo.

Politics, the invention of a revolution

Frida Kahlo’s production, both of her work and of herself as a public figure, is part of a period of upheaval and national transformation. Born in 1907 – although she liked to say that she had been born with the beginning of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 – she was part of a project, never unified and rather ambivalent, contradictory and in dispute, of shaping the modern nation emerging from the turbulent revolutionary process. A process that some historians mark from 1910 to 1938, when the presidential programme was consolidated with the government of Lázaro Cárdenas.

In this long period, art, and especially muralism, played a leading role. It gave shape and support to the dreams of several revolutionary processes, as well as its sedimentation as a national project in different governments. It was a way of being seen, of making visible. It was a way of entering modernity and pointing out where progress should lead.

From a wealthy family, Frida, unlike many other women of the time, studied at the National Preparatory School, with the intention of later starting a career in medicine. There she not only had an education in the progressive “spirit” of the time, but also had very close relationships with people like Alejandro Gómez Arias, a writer who, after their relationship, played an important role as a leader of the student movement of 1929. There she also met Aurora Reyes, a communist muralist with whom she had a deep friendship for the rest of her life

Her letters of the time show her knowledge of political events, although they do not establish any radical position regarding them. Her encounter with Diego Rivera in 1928 marked her entry into a political programme, one that shared the movements and ideologies of the time but also had elements of its own, which they not only shared but, I think it is fair to say, they invented and nurtured together.

I think it can be said that Rivera was one of the most important aesthetic and political organisers of the modern process in Mexico. Part of the project was to generate a platform for propagandistic indoctrination that, through art, would generate a common representation. A figuration to follow. To give a perspective on the importance that this movement, or this series of movements, had in the country, I find this comment by Lacan interesting.

In 1966, the French psychoanalyst visited Mexico. In the explanation of his trip, he spoke on the existence of a past in its perfect form. This perfect past was manifested in Rivera’s and O’Gorman’s murals in which they inscribed the past in a way that never existed. What happened there was, in the words of Lacan, something enigmatic and amazing, what the murals vehiculated was “an invisible bond through an irreparable tear that subsists across generations”.

Muralism was the process by which a future time was shaped seeking to unite denied and broken pasts. The conquest and the colony were articulated with a series of revolts that turned out into the triumph and consolidation of a nation reborn from a revolution that promised social justice. It was an invention, a vehicle for a time to come.

Rivera’s muralism, which is very different from that of Orozco or Siqueiros, was the creation of a Mexican artistic avant-garde that united European pictorial forms – fresco techniques and Renaissance perspectives – with local figurations and inventions that marked their own idea of modernity. All this, as suggested by the historian Luis Vargas, under the ideology of presenting a resolved history:

“The mestizo and now revolutionary nation was a sovereign and modern nation, which viewed the Conquest of Mexico and the colonial period with disdain. The post-revolutionary rhetoric and official murals promoted the idea that although Mexico had achieved its independence from Spain in 1821, it was not until after the Revolution and the 1917 Constitution that the country truly achieved political, democratic and social justice maturity.”

At the core of Rivera’s aesthetic-political programme was a revolutionary project that would give way to a socialist policy of agrarian and workers’ integration. The murals in the ENP Amphitheatre, where Frida studied, and those in the Ministry of Public Education building (1923-1928), where Frida herself is depicted, are central to this project. Commissioned by the first minister of education, José Vasconcelos, during Obregón’s government (1920-1924), we can see, as Renato Gonzáles Mello asserts, how painting is part of the political invention of identities:

“Mural painting was crucial in developing this emerging social and political identity, at a time that was far from becoming the rhetorical category of the Revolution. Therefore, […] it is not that painting has taken its categories from politics, but it contributed to articulate political categories and identities.”

The Ministry of Public Education murals were important, among other things, for figuring the category of the peasant as a political identity. As González Mello points out, Rivera had previously painted the rural and indigenous population who had no legal name, “who had no precise title in politics”. A population that was not “exactly” the working class and that needed an identity in order to enter into the revolutionary project. This figuration, as a political-aesthetic category, emerges in these murals.

This agrarian-worker alliance may have been one of the causes of Rivera’s expulsion from the Mexican Communist Party, but it was undoubtedly one of the great political interventions of the time.

In addition to the revolutionary proposals in the Ministry of Public Education murals, which are not found in such a compelling way in any other work by the painter, I am interested in the fact that this is the first work by Rivera in which Kahlo is portrayed.

In this 1928 panel, known as The Arsenal, she is presented as a communist militant handing out weapons to the workers – intellectuals would be part of the avant-garde alliance in a rare and original Saint Simonian update. Frida is portrayed in several murals, always as an agent of the coming revolution. Perhaps in them we can see the role that Rivera envisioned for her, but as we shall see, it is not the role she took on nor how she presented herself in her work.

I am not referring to Rivera’s work in order to subordinate Kahlo’s place and her representation in Diego’s work, but to point out the rising of the Mexican for this revolutionary project, for it is configured with elements that are present in Rivera’s work but also in Kahlo’s. Both artists share a political programme that requires a sensible mobilisation, which needs to make other objects, subjects and sensibilities appear.

Some of them take shape in the use of popular objects – when there was still a tight separation between high and low culture – and which they radically promote in order to characterise a Mexican plasticity, materiality and originality. The centrality of craftsmanship and popular objects had already been appropriated by artists such as Dr Atl and was a constant in the artists and intellectuals of the time, but Rivera and Kahlo were undoubtedly the ones who took it to another dimension in their work and in themselves (their characters, their costumes, their collections, their houses).

Also, and which is fundamental, is the incorporation of indigenous ethnicity. This incorporation was not the vindication of the original peoples – we must be very clear about that in the light of contemporary demands – but their integration to create a mix, mestizaje, that would allow the emergence of a more or less unified people with a common “destiny”.

The exoticisation of Frida Kahlo, her character but also her work, is based on removing these elements from their context of politicisation.

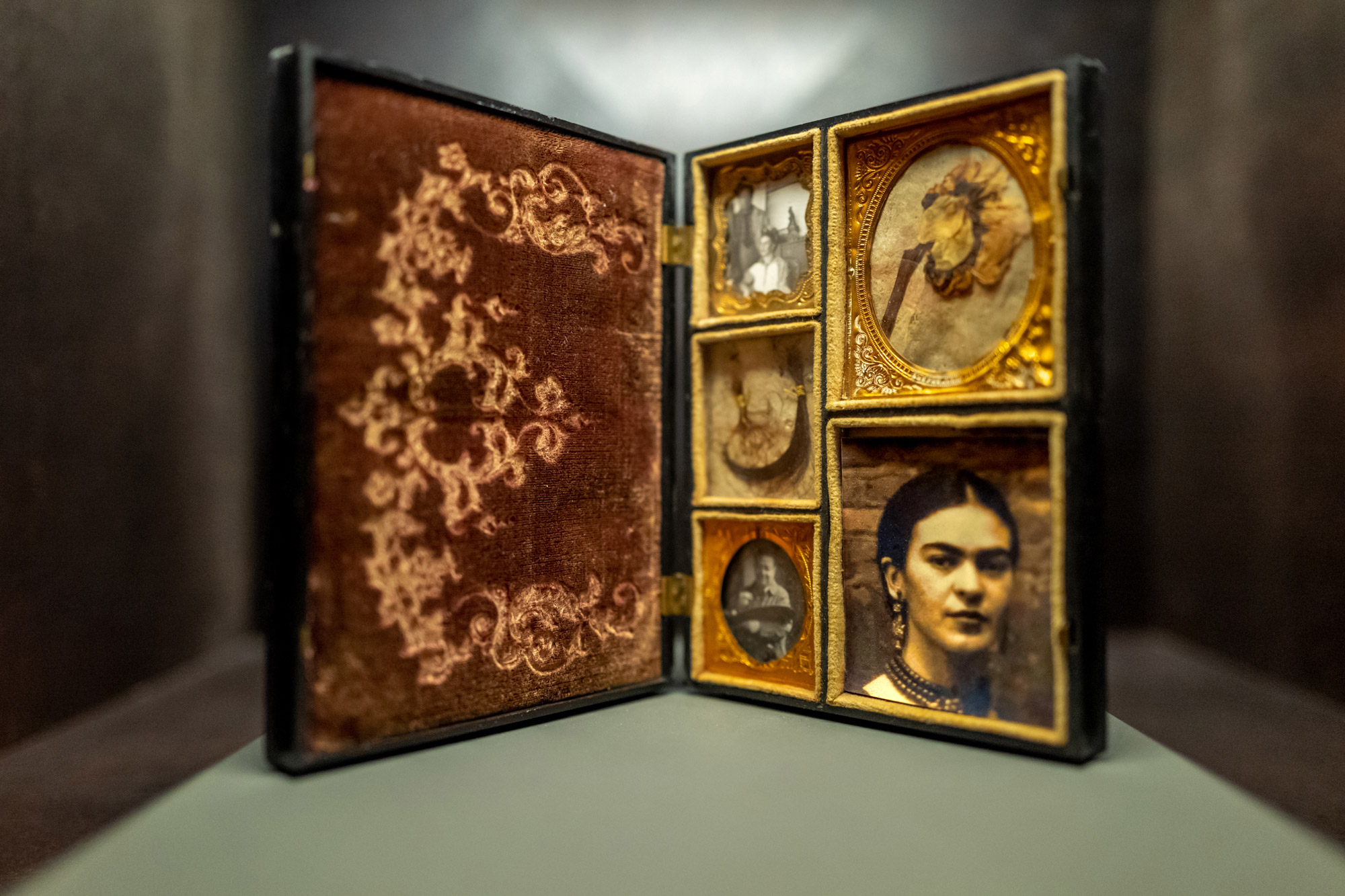

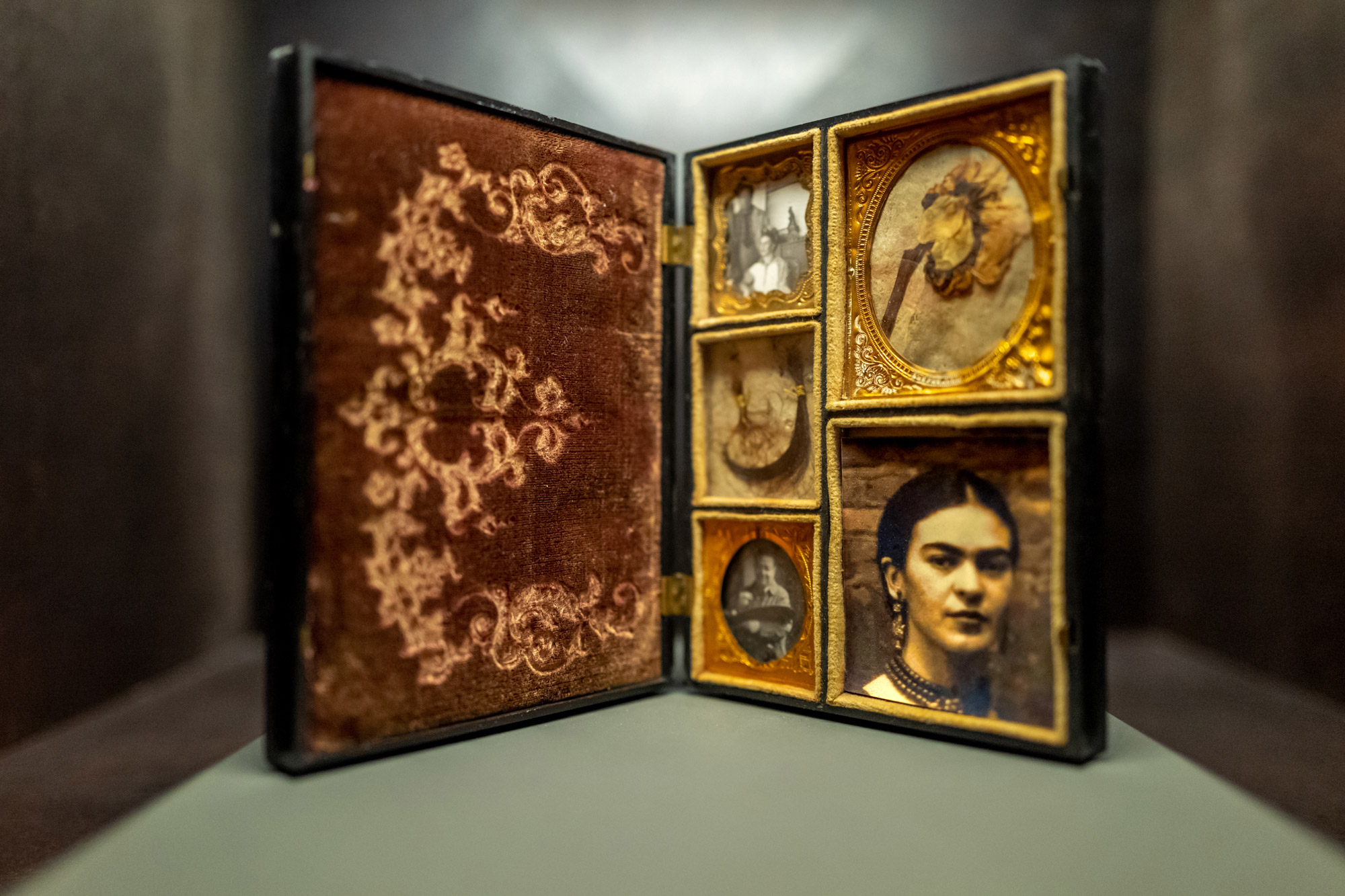

For example, there is a clear attempt to characterise her by her use of indigenous dress, as if this were a characteristic of claiming identity. Indeed, Kahlo wore traditional costumes such as the Tehuana dress, like many artists of the time, as the Juchitecas represented a force of female social and political organisation that had been consolidated in the national imaginary since the 1920s, but it is left out that she also wore dresses associated with the rural world, as well as Chinese ones and men’s clothes. The Mexican identity is also emphasised in the significance of her collection and the incorporation in both her work and her house in Coyoacán – which is undoubtedly a work of art reformed by O’Gorman – of handcrafted and historical objects belonging to pre-Hispanic cultures.

All of this is part of the invention of something that did not yet exist as such, but under a specific political prism create an aesthetical essence of Mexicanity. That operation uses aesthetics and art to give body and shape to a political subject still absent in the field of representation and historical struggle. Beyond exoticising her with these elements, in order to define her, we could think that there is nothing fortuitous in her use of them. They are not a symbol of innocence or exoticism, in any case it is the creativity and insistence of raising a political programme in alliance with art and, in some way, with life.

What I am interested in opening up, with this framework in mind, is the specificity of Frida Kahlo’s political operation in her work. Although Kahlo takes up imaginaries, fabulations, figurations and representations that are part of an aesthetic repertoire she shares with Rivera, her battlefield will be elsewhere. It will not be played out in the same cultural, artistic or political space. The pictorial representation of Frida Kahlo is a bomb that points in another direction. It is no longer the construction of a historical time but the creation of a world from where the self, herself, plays as a space of representation for a series of blocks of affects and intensities to explode.

A place of her own

The place that Frida Kahlo’s work made appear is interesting, a liminal space of the intimate that has political consequences for the present. Frida’s work distances itself from the propagandistic and public operations of Rivera’s muralism. She does not try to represent the people or history, but herself. Without, however, abandoning the aesthetic-political elements of her programme for the future.

This intervention has some surprising peculiarities. On the one hand, it is separated from the artistic operations of contemporary artists, such as Remedios Varo or Aurora Reyes, who did promote a body of work as a space for a local career. Although Frida assumed herself as a painter, an activity she would carry out with different intensities after her accident in 1925 in which the bus she was travelling in with Alejandro Gómez Arias crashed and broke her into a thousand pieces; she did not have as prominent a career as other female artists of the time in the country. She certainly had a presence and success abroad (in 1938 a solo exhibition in New York and in 1939 she participated in a collective exhibition curated by André Breton in Paris), but, let us remember, her only solo exhibition in Mexico was curated by her friend, the photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo in 1953, only a year before she died.

On the other hand, she was not outstandingly politically active either. Although she was an important figure on the cultural and public scene and had, as seen from her relationship with Leon Trotsky, who was exiled in Mexico between 1937 and 1940, a significant degree of intervention, she did not seem yearning to operate in the militant field.

These were not easy times for women’s militancy. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, although women’s participation in the Mexican Communist Party was significant, it was clear that the priority of the agenda was the struggle for class and production conditions and that suffragists and women’s rights struggles would be relegated. This generated annoyance and disappointment among many of the collaborators, which led, as studied before by historians such as Dina Comisarenco and Deborah Dorotinsky, to the opening up of these agendas on other fronts, such as the cultural and artistic ones.

Even so, artists like Tina Modotti, Aurora Reyes and Concha Michel – all three of them very close friends of Frida – were active in the political field, as well as in the artistic field, with the distances from the Communist Party or subordination that each of them needed or endured. This was not the case of Kahlo.

She took another direction, perhaps because those were the possibilities she had at hand. Although today it would still be necessary to explain in what sense we understand the political intervention of her work, in the 1930s and 1940s, under the shadow of muralism, it would be difficult to think that her production could be understood in a political field. She was Rivera’s wife. A woman who, although some of the critics of the time considered talented, had no formal studies and her painting was considered naive and intuitive.

Despite these readings, some contemporaries, besides Rivera himself, managed to see the radical nature of her work. Breton categorically announced: “The art of Frida Kahlo is a ribbon around a bomb.” Perhaps her artistic project has a dimension that could only be open in the future, once the bomb had exploded.

Her work tends to be read as an obsessive presentation of herself, her life and her feelings, her suffering. However, it seems to me that the operation she presents has much more complex dimensions. During an interview with Parker Lesley in the early 1930s, Frida declared that she wanted to make self-portraits of every year of her life. The central body of her work, her self-portraits, thus appear as a research project that goes beyond presenting herself out of obsession or vanity. It is, perhaps, as Gannit Ankori points out, the creation of a life through different selves, which are her but also something else. An identity that, besides its fixed points, is also fluid, mutable, contradictory and ambiguous.

Self-portraits

Self-portraits are a strange device; they are undoubtedly a way of representing oneself, but that presentation does very different things throughout history. In the book Seeing Ourselves, Women’s Self-Portraits, Frances Borzello writes that self-portrait could be considered, owing to its importance in the history of art, as a genre itself. And that women’s self-portrait specifically, because of the historical conditions of women’s representation, presents a vital space for the artistic work and agency of female artists.

The self-portrait of women is not exempt from prejudices that attempt to relate this affinity with the personification of the vice of vanity without considering the different operations it has served. From the development of techniques and skills, to the need to make oneself appear either as a personal gift or as a public act. The self-portrait has been a substantial space in art not only to be seen but to present how we see, feel and find ourselves. A double not only implying an externalised interiority but that can also be the presentation of historical conditioning, ruptures and desires. Although the self-portrait of women has a long history, dating back to the 13th century, it was in the 20th century when it became a substantial tool for social exploration and political critique, where ambiguities, tensions and possible futures of the representation of women emerged from new subjectivations outside the capitalist and patriarchal mandate. This is where Kahlo’s operation and research steps in, she exteriorises while also projects. It is a complaint as well as a demand.

In her analysis of the history of the female self-portrait, Borzello states about Kahlo: “No artist, male or female, has produced a body of autobiographical work to match its originality.”

The statement must be true; however, it seems to me that radicality here lies not only in the originality of Kahlo’s work but in what the conceptual operation of portraying herself throughout her life sustains. Not only from the moment she began painting, that is, when she was 17 years old, but when recreating her life in these presentations.

What I think these paintings do, beyond establishing an autobiography, is to open up the personal and the self-representation to the complex social and historical construction of being a woman. Of being a woman in Mexico at the beginning of the 20th century, of wanting to participate as an emerging political subject, of being subject to the gender and romantic mandates of the time – which have changed a little, but not much. And, at the same time, being free or wanting to be free in order to become what one is and also what one is not. To be what one is not yet, but that by presenting it, is someway already being.