Long Read | Freedom’s footprints: Freire and beyond

Ideas of freedom were in the air and mass strikes on the ground. Durban in 1973 saw the dream of freedom turning towards a strategy to realise democratic socialism.

Author:

27 October 2020

Out of the dawn they streamed, from the barrack-like hostels of Coronation Bricks, the expansive textile mills of Pinetown, the municipal compounds, great factories, mills and plants and the lesser Five Roses tea-processing plant.

The downtrodden and exploited rose to their feet and hammered the bosses and their regime. Only in the group, the assembled pickets, the leaderless mass meetings of strikers and the gatherings of locked-out workers did the individual have an expression of confidence.

The solid order of apartheid cracked and new freedoms were born. New concepts took human form, the weaver became the shop steward, the mass of organised overtook the unorganised, the textile trainer became a dedicated trade unionist and the shy older man a reborn Congress veteran, while the sweeper came to be a defined general worker.

A class was standing up and challenging the system, not yet armed with the sharp ideas of alternative society but working away at the contradictions breaking open in the system of race and class.

Related article:

Nobody had expected such an explosion of solidarity and strength from the base of society. Economic growth had accelerated the expansion of large textile mills and factories in the Durban and Pinetown industrial areas. The quiet subterranean processes of accumulation of strength from below was very much in the background of those thinking about overthrowing apartheid and building a new society defined by equality and plenty.

There were such minds at work and ideas in the air, on paper, in pamphlets and in books. There were also lively discussions in and outside workplaces. Even as existing freedoms were being crushed by the regime and political association between black and white made a crime, freedom was in the air – so long as the right to read, to think, to reason could be exercised. And to learn to resist in new ways. All this became keenly exercised to broaden and break out of the existing constraints, through a vision of an entirely different society.

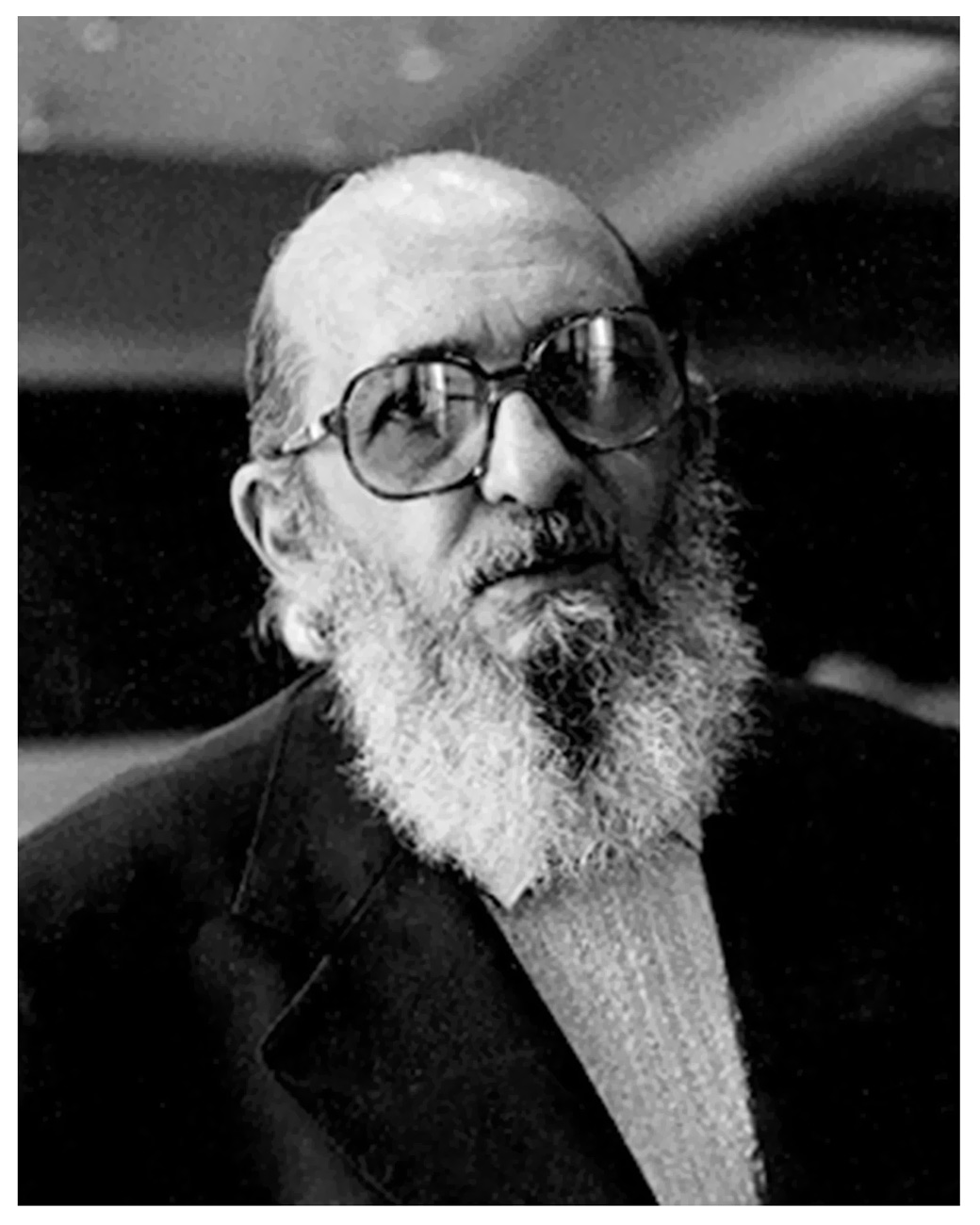

Steve Biko and Rick Turner

Two particular minds were at work: one in a wood-and-iron house in Bellair, Durban, and another in the shadow of the reeking, rumbling Wentworth oil refinery in the Alan Taylor residence. They would become close friends, and after bursts of energetic writing and political engagement, both would die at the hands of the apartheid security apparatus. Both were influenced by Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, with ideas and concepts in this magnum opus infused and woven into their own writings striving for freedom.

Much of the thinking of the time is evidenced in these publications. Rick Turner published The Eye of the Needle in 1972. And in the shadows of the oil refinery, Steve Biko was writing a series of incisive political essays from 1969, when he became the president of the South African Student Organisation (Saso), to 1972 (and leading to his ban in 1973). These were later published as I Write What I Like. From Turner came a method of rigorous thinking out of dystopian apartheid, and from Biko the vision of black people coming to consciousness and making themselves anew to achieve freedom.

In various combinations of individuals and groups, the Durban moment has been captured in writing that usually sets the strikes as the background to flourishing ideas. This moment, however, was more than a point in time, a snapshot, and the contest of ideas. Rather, there was a shift to movement in a city whose docility and passivity had dismayed Clements Kadalie of the Industrial and Commercial Union (ICU) in the 1920s but also shown its volatility. A few years later, troops had to be flown in to quell the workers movement. The striving of the dispossessed was to turn this point in time into a permanent movement for continuing change, and the setting was colonial Durban.

These writers took up elements of the developing practice led by Freire: the realisation of colonial oppression that then opened up a method of teaching that emphasises critical thinking to achieve liberation. Here were two minds living in the same milieu while physically separated by the spaces of apartheid. When they could meet, the luxury of each contact was used to the full. In the excitement of the moment, it appeared that the world of apartheid oppression could lead directly to a new liberated world. Both writers were occupied by the idea of conscientisation: ruthless critical examination of the dominant oppressive thinking of the time.

From Turner, there was a search for agency through enlightened individuals, the church and potentially from black workers; from Biko, the agency of a mass of black people conscientised by students and community activists.

There was something of a common or parallel understanding. The black mobilisation and civil rights movement in the US, the general strike and student uprisings in France in 1968, the African armed struggle for independence… all these were common reference points.

Related article:

Both also understood something of the problem of Stalinism, which carried the promise of international solidarity and socialism while being based on the dictatorship of a national elite over working people. Turner’s students deliberated over Sartrean theories on the degeneration of the Russian revolution. The increasingly sclerotic bureaucracy was visible at the time but not the underlying rot and need for a political revolution or collapse back into capitalism.

Apartheid, however, appeared the all-enveloping world problem in itself. Starting from this epicentre, they considered the international and local social forces to support the struggle for freedom.

An internal reference point was the discussions of strategies for change convened by the Study Project on Christianity in Apartheid Society (Spro-cas). Confronted by an obdurate apartheid, the best minds came up with proposals for minimalist reform such as drawing Bantustan leaders into discussions of the future. This minimalist approach was repudiated by Biko and explored and expanded on by Turner in The Eye of the Needle as the first by-product of his engagement in Spro-cas.

‘Out of the apartheid box’

In his book, Turner took the dominant Christian ethical framework and worked through the contradiction between these principles and the ugly practice of white power. Sub-titled Towards Participatory Democracy in South Africa, it gently but rigorously exposed this practice and advocated utopian thinking to “think out of the apartheid box” to resolve structural racism through the creation of a socialist society.

A close reading of The Eye of the Needle with its reference to a Christian framework was not eagerly undertaken by young radicals. Here was no manual but the exploration of an exacting method.

Turner writes that although utopian thinking (the possibility of a non-racial society) appears to run counter to common sense (that racism is inherent in society), this is unscientific and obscures reality. He explores the (im)possibility of resolving poverty, the oppression of women and human inequality, and applies the test of realism, which finds that utopian propositions are more practical than those of common sense or realism. The reader is walked from the dream to an examination of human nature, socialisation and the possibility of alternatives to arrive at the necessity for socialism.

Here was a persuasive argument for the necessity for socialism to resolve the inequalities of race and class, but it stopped short in exploring the instruments for its realisation. Utopian thinking entertained a vision, but left an open gulf for its realisation. Turner took to training sessions with nuns on the East Rand and adult classes to explore utopian thinking and the resolution of the inequalities of race and class.

In his academic teachings, Turner created a strict regime of tutorials defined by the close reading of texts and asking demanding questions. His white graduate students ground away on the question of Sartre’s café waiter. The waiter – acting in bad faith in denying his own freedom even though possessed with it – uses this freedom to deny what he had. You may know you are free, but choose not to acknowledge it. For those looking for a political manual to change society, there was instead a diet of difficult texts, demanding debate, and the tutelage of exact reasoning.

For his students, the road from Sartre to the dock workers was uncharted. Many of Turner’s graduates then took other routes to the future, deeply influenced by engagement with forceful intelligence and the lively example of his living in freedom in a marriage that defied the prevailing racist laws. They faced the challenge of bad faith or living in freedom.

Aware of the yoke

Not many people could not be influenced by Biko. It is unfortunate, however, that only a few read the riveting emancipatory essays he penned as Frank Talk.

The black consciousness strategy he advocated insisted that black people had to break the chains of servitude and lead a social, cultural and political awakening in their own country. He exposed the fraud of the regime’s Bantustans and denounced politicians who had “already sold their souls to the white man”. Of Mangosuthu Buthelezi, he was particularly critical. He did not know then that it was the strategy of the ANC to incorporate Buthelezi into its fold and support Inkatha, despite its acceptance of and participation in the Bantustan system. Today, the details of these intrigues, which were never explained to the militants of the time (then or later), are documented in Luli Callinicos’ biography of OR Tambo.

Related article:

There were others conscious of these developments and determined to break out of the boundaries of race and class. There were other ideas and strategies in the field more frankly based on Marxism. Those involved in the Wages Commission explored the foundations of cheap labour as the source of superprofits and took the ideas of freedom and the method of Marxism into the field of mass struggle. In discussions with dockers, abattoir workers and those in the major factories, it was clear that workers already had the foundational understanding mentioned by Freire of knowledge of themselves and their oppression.

These Wages Commission operatives found the black worker, particularly the migrant worker, far from being (in Biko’s description) “defeated, drowning in his own misery, a slave, an ox bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity”. Discussions found that black workers were keenly aware of the yoke and wanted to break free. The question was, how?

Material conditions determined consciousness. Though they realised they were not free, they still knew they had agency and were eager to gain the ability to decide their future as an oppressed people and as a class. They already knew the purpose of their being was to benefit their bosses, they knew they were treated as things or objects that exist merely to serve the bosses’ orders. They knew their race, work and culture were constantly demeaned by a system of oppression.

There was a clear consciousness of racism and exploitation. Black people knew they were on the receiving end of the regime’s racist systems. The question was how to resist without immediately losing everything: a job, permission to be in the city, etc. How to resist and still avoid imprisonment and deepening poverty?

How could the workers, together with the “teacher”, craft the instruments of resistance that did not lead to reversals or obliteration? Nobody was quite sure of the boundaries, the possibilities for freedom and limits of repression. These could only be known after the fact of strikes, collective action, demands, mass strikes, reinstatements or permanent dismissals. Migrants who had some land were the toughest resisters, prepared to fight, lose, retreat to the homestead and return to fight again.

The pedagogy for the oppression and resistance was easy in outline but difficult in practice. The rising unions wanted a utilitarian instrument of training rather than discursive education. A new layer of leadership in the factories knowledgeable about organisation, basic industrial law and knowing how to build effective solidarity was needed.

The wide range of possibilities for freedom developed into contested streams. Was the pedagogy to be that of the Marxism of Wages, Price and Profit or the manuals of trade unionism within the capitalist framework?

An important tool

With divergent strategies, who would teach the teachers, what was there for the teachers to learn? Colonial rule and apartheid practice had built a patriarchal structure deep in the Bantustans that ensured cheap labour to the cities and the domination of black women. The superstructure of apartheid rested on the apparatus of force and the society from which resistance sprung was far from being firmly democratic even while resisting the totalitarianism of apartheid. Nascent tyrannies also lay at the base of a society unused to democratic practice.

The danger of the brutal Bantustan apparatus dressed with political clothes as in Inkatha marked the rise of a new tyranny in the midst of the struggle for freedom. This was unforeseen by Turner, warned by Biko and the daily subject of contestations in the unions. The Marxists in the rising movement saw Inkatha as South Africa’s Kuomintang, an apparent nationalist movement that would turn, when opportune, to decisively crush the workers movement if it could. This was a prognosis proven over time.

Related article:

A praxis – the universal, creative and self-creative activity through which humanity changes the historical world and the individual – evolved. Social action broke out of the context of the didactic and a pedagogy and changed the relationship between teacher and the taught. For a while the teacher could be the organiser, a knowledgeable expert, with the subject being the oppressed worker. But not for long. These inequalities had to be resolved somehow. Some brilliant black organisers such as Bhekisisa Nxasana were forced out of leadership by threats from the Security Branch and had to limit themselves to teaching and translation. There was no easy walk to decisive black union leadership.

In truth, the “teachers” had much to learn about the militancy of women workers; existing networks in the workplace and society; the underlying loyalty to the ANC when there was the opportunity to safely express this; the spirit of the Mountain (of rural armed resistance against chieftainship in Pondoland), the militancy of many migrant workers; how to struggle for reforms without becoming reformist; how to exercise leadership without tutelage; and what approaches to adopt to maintain workers’ control over leadership in the union.

With this learning from experience, the teacher could no longer assume an audience and teach as before. Rather, the “teacher” had to listen, learn and relearn the nature of the politics of resistance and of deadly reaction. Only then could the replication and deepening of leadership happen, through strategies such as training the trainers.

Union leadership

Later, the unions would face the challenge of organising self-defence strategies against armed reaction in communities and the factories.

Most of all, those unionists who were white had to learn how to encourage and develop black working-class leadership, to give everything but prepare to depart and possibly take a new role in the revolution. This appeared easy in the beginning but became more difficult as every advance in the movement was matched by wave after wave of detentions and bannings. There was no conscious political underground as prior to the Russian Revolution, to organise forces of workers for democracy and socialism secretly or (partially) openly.

The mass strikes had changed South Africa, specific gravity had shifted in society. Those at the base producing textiles, blankets, fine fabrics for suits and dresses; the dockers shifting exports of sugar, coal, ores and mielies; the machinists and those in company overalls now carried ideas.

While not swaggering, they knew they had agency, the mass strike, and an instrument being honed: the trade union. There were new leaders emerging from the factories. Women workers such as the fiery former weaver June-Rose Nala took their places directing the unions. The ideas of democratic, worker-controlled trade unions for the struggle were firmly implanted.

Related article:

Even though the growing labour movement was eclipsed for a while by the militancy of the generation of the 1976 uprising, it had the growing strength in numbers and depth of organisation that was necessary to wear away and then crack the granite of the apartheid state. The remorseless struggle for a living wage and workers’ control in the factories was breaking up the cheap labour system and blasting away at the foundations of the apartheid system.

New ideas and incipient organisations arose in the midst of intense and sometimes bitter controversies. Some are now inconsequential, but many connected with the sharpest edge of struggles today. These include methods of dealing with union bureaucracy, reactionary nationalist politics, the assassination of workers, the dedicated, open and honest management of money, the open accounting of union funds and investments, and the struggle for internal union and wider social democracy. Many of these have to be struggled anew.

Differences over Inkatha

Our two thinkers had differences over the rise of traditionalist politics of Inkatha. Turner was open to it, seeing it as a rural social movement. Biko was against Inkatha’s collaborationist base in the Bantustans. Both underestimated workers’ underlying loyalty to the ANC, as the traditional organisation of the people. Workers remained loyal despite the dead decade of the 1960s, the early years of its ban and its shift to the underground.

Neither could have guessed that the rising instrument of reaction had the explicit support of the ANC during the 1970s. Those finishing their time on Robben Island were embarrassed to confess that, as revolutionaries, they had been instructed by ANC leaders to take the stage at Inkatha meetings to show support for Buthelezi and Inkatha. William Khanyile, then working in the Umkhonto weSizwe underground, felt too uncomfortable to pass on this command to comrades in the unions. He burned with shame when he was called up to the platform by Buthelezi at a mass meeting in Vulindlela.

Critical thinking involved going a step beyond the pedagogy of literacy, well beyond the universal but basic relationship of conscientisation, and turning the knowledge of oppression into organisation. A praxis evolved in which the trade unions were sharpened, tested and reworked, and turned into an instrument for lasting irreversible change. Those of the time anticipated that this would be democratic socialism (not models of dictatorship from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or China), with working people in control over every aspect of their lives and in command of the state (not corrupt cadres).

Literacy training

Over time Biko returned to the Eastern Cape to serve his banning order by the government. From there, he participated in the health and other projects of Saso and the Black Peoples’ Convention. Inspired by the strike movement, Turner turned to writing, secretly with others, The Durban Strikes 1973: Human Beings with Souls, which carries the most graphic descriptions of this uprising. His energies focused on building the Institute for Industrial Education to help develop a black leadership.

The practice of literacy training changed with the changing context. When Pat Horn came to the unions in Durban in May 1976 to undertake literacy training to support shop stewards, she found an uneven field of work. The gaps made by waves of bannings meant that anyone capable had to work at new priorities. She did some literacy work but also worked alternatively in the union offices in Pinetown and then the union local in the Jacobs industrial area.

Related article:

“Literacy training became a secondary activity as we worked through the factory committees and infiltrated these to win places for elected shop stewards committees. Since this is what the law allowed, we’d take advantage of this. Literacy training was swallowed up in this work,” said Horn.

Freirean literacy training met a complex of attitudes. Most workers were literate in Zulu, but as shop stewards they wanted to be in command of English to negotiate and read the agreements reached. So, there was an element of English literacy.

Literacy training then became more practical than political. Controversies over goals, strategy, alliances and workers’ democracy emerged and became set points of difference made urgent by spates of bannings.

The beginning of an end

Everything was changing, utterly changing. Steve Biko’s intellectual acuity and political brilliance was snuffed out on 12 September 1977, bludgeoned by the security police. He was only 30 years old. Soon after, Rick Turner was shot to death at his home on 8 January 1978. There was no time for reflection and synthesis.

The differences in vision and of strategic allies were not incidental and burned away at the collective energy of the movement. The destiny of a movement to end the cheap labour system and apartheid was at stake, but discussions were now blocked by banning orders or broken up by Security Branch raids. Would the unions develop into a revolutionary force or take the contours of capitalism, become subservient to middle-class nationalists or even get impaled in a fatal alliance with rising reaction?

Such controversies went well beyond a seminar discussion. Unresolved, these strategic political issues slowed down the dynamo of Turner’s creative genius. The carefully constructed shop steward manuals he diligently produced during conditions of his banning remained unused. Despite this, these unions became the foundation stones of the Congress of South African Trade Unions and the South African Federation of Trade Unions.

If there could be a wandering road from Sartre to the docks, there has been an even longer road from incipient militant trade unionism and the struggle for democracy and workers’ power in communities and workplaces. This is a struggle in which we are still engaged. What does it mean to be free?

David Hemson was among those who sought to make the revolution in permanence. Acknowledgement to Pat Horn for sharing, to Halton Cheadle who was my close companion in struggle, to William Khanyile in the Umkhonto weSizwe underground who shared the pain of Inkatha, to Bhekisisa Nxasana who chuckled at contradictions and made things work, and to June-Rose Nala who taught us all to be bold.