Live recordings from Mauritania deserve a shout-out

A reissued compilation offers a fascinating gateway to the country’s thrilling post-independence music that is rarely heard outside its borders.

Author:

24 February 2022

The relationship between musician and audience has suffered dearly during the Covid-19 pandemic. Though some may argue that live-streamed performances are a reasonable substitute, both musicians and their fans know that a live performance is a two-way relationship. Without an audience to draw energy from, musicians struggle to reach those heights that make the live music experience so thrilling.

In Mauritania there is a popular Arabic exclamation – “wallahi le zein” – that audiences utter when they are taken with the performance of a live band. Translated it means “I swear to Allah this is great”. Audiences understand the moment of transcendence encapsulated in this phrase because it is what drives them to seek out live music.

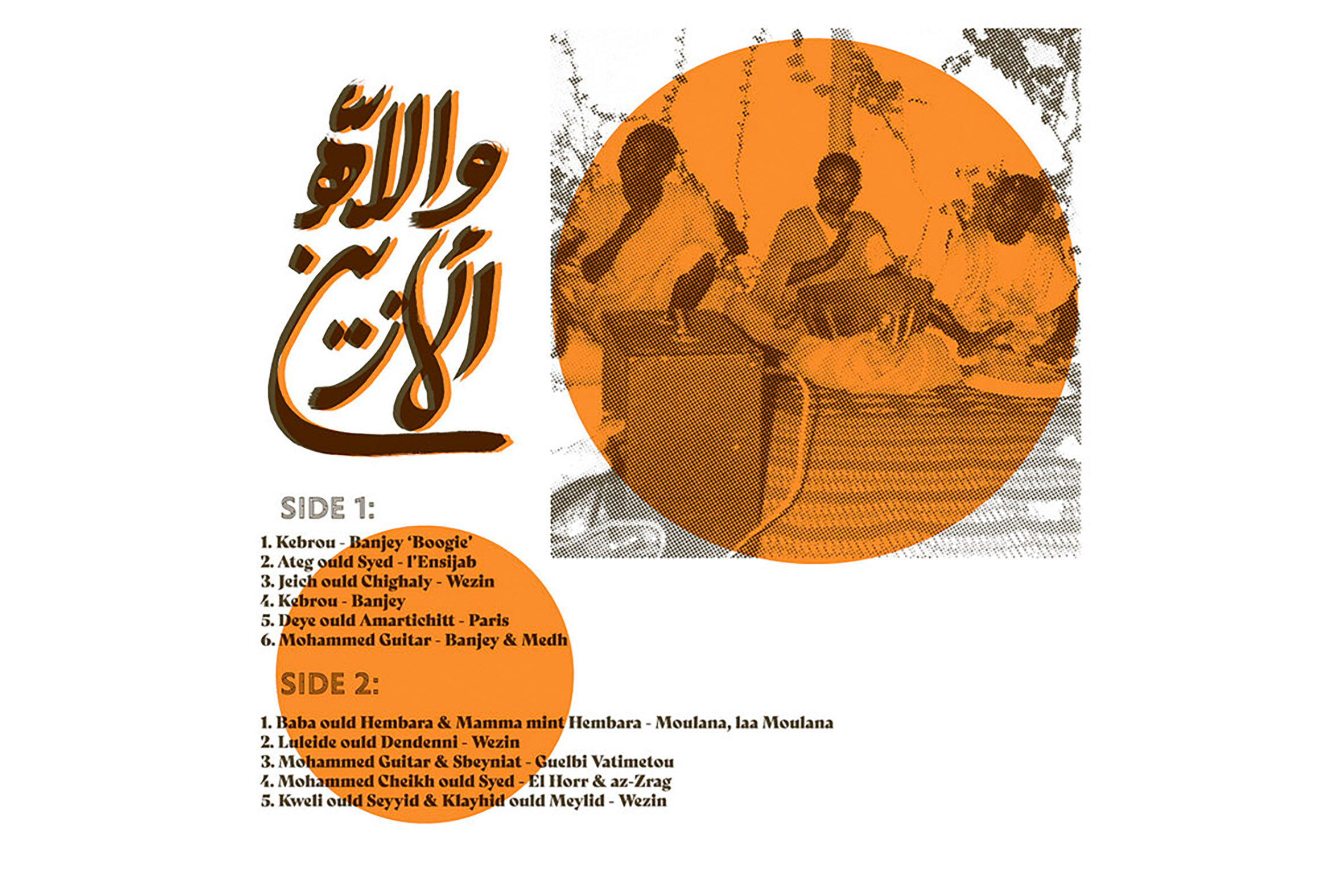

It is fitting then that a compilation of live recordings that document Mauritania’s musical scene since independence in 1960 should be reissued to act as a welcome respite from these days of musical isolation under a global pandemic. Titled Wallahi Le Zein!, it offers just under two hours of music with its 28 curated recordings.

Related podcast:

Whether it’s the knotty guitars of Kweli Ould Seyyid and Klayhid Ould Meylid, the fuzzed-out guitar histrionics of Jeich Ould Chighaly or the psychedelic twang of Luleide Ould Dendenni’s six-string, the recordings are intimate affairs in which the relationship between the musicians and audiences are tangible.

Wallahi Le Zein! is a gateway to a hidden history of Mauritanian music that leaves the listener in no doubt as to why the two-way relationship of live performance can never be replicated by digital screens.

Born to be musicians

Before Mauritania gained its independence from France, music had been firmly locked in a rigid caste system. Like the griots of Mali and Senegal, Mauritania’s musician caste, the iggawin, were born into their lowly status and functioned as praise singers, social historians, poets, newscasters and entertainers. The iggawin’s music, known as azawane, had remained relatively stable between the 18th century and 1960 and was composed using a strict system of modes derived from Arabic music theory.

Azawane was also strictly divided in terms of gender, with an instrument like the tidnit, an hourglass-shaped lute with four strings – very similar to the Wolof khalem or xalam and the Mande ngoni – designated to be played by men. Conversely, the ardin (angular harp similar to a kora with 10 to 14 strings), tbal (kettle drum) and daghumma (rattle) were played only by women.

Related article:

At the new millennium, this music of Mauritania was still mostly unknown in the rest of the world. When The Rough Guide to World Music was published in 1999, only a handful of albums from Mauritania had received commercial distribution beyond the country’s borders.

At the time, the most famous Mauritanian musician was Dimi Mint Abba, who had been born into an iggawin family and performed alongside her husband, Khalifa Ould Gide. The duo’s 1990 album, Moorish Music from Mauritania, released by London-based World Circuit Records, was what the world considered to be Mauritanian music.

However, Moorish Music from Mauritania represents just one facet of the country’s music. Revellers at weddings and birthday parties were familiar with a far more thrilling form of local music, even if Westerners were not.

Loosening up

Under the pressures of rapid urbanisation in post-independence Mauritania, the rigid caste system’s grip on music had begun to break down and musicians started emerging from all over society. As these changes took place, the role they played also began to shift towards social occasions such as marriages, baptisms and birthdays.

Mauritanian musicians began to embrace new instruments too, transposing tidnit melodies to electric guitars, which were often customised by removing frets. The sound was then run through distortion pedals and phasers built into the guitar bodies to facilitate spidery psychedelic explosions.

For 50 years, these developments in Mauritanian music remained hidden from the rest of the world. Then a former presenter from Voice of America’s Music Time in Africa, Matthew Lavoie, decided to change that. Over a number of years he had been building up an archive of lo-fi cassette recordings of live performances from Mauritania that captured this new form of music.

Edited down to 28 recordings and released on CD in 2010, Lavoie’s compilation, Wallahi Le Zein!, was hailed by critics and fans on its release. Now, more than a decade later, the Chicago-based label Mississippi Records has reissued it digitally as well as on vinyl and cassette.

The first five songs on Wallahi Le Zein! are examples of banjey, the music of the Haratin people, which had not been widely recorded before. The Haratin do not have a griot class and they do mostly work songs, religious praise songs and celebratory dances.

These songs take the form of explosive guitar pieces that ride over the top of fast-paced rhythms driven by drums and handclaps. The sheer intensity of these performances and the audible responses from the crowds make this critic wish that more of these Haratin recordings had been included.

Intense experiences

The remaining 23 songs on Wallahi Le Zein! document the azawane music of the Beidane people, which is divided into five modes of composition that are meant to be performed in a strict order. These modes are known as the karr, vaghu, lekhal, lebyaal and lebteyt and the Beidane section of the album is sequenced to follow this pattern, with the listener taken through examples of each mode in order.

Some of the recordings are examples of combinations of two or three modes and are reflected as such. For example, Mohammed Cheikh Ould Syed’s six-minute El Horr & az-Zrag moves from vaghu to lekhal to lebyaal.

While the power of Wallahi Le Zein! is very much tied to the listener’s immersion in the music as a whole, there are a number of standout recordings. The nine-minute Henoun by Baba Ould Hembara and Isselmou Ould Hembara starts like wild wailing blues, with a psychedelic guitar snaking around the singer for three minutes. Then a drum arrives to accompany the guitar as the song builds in intensity. The performance, like all the greatest music, emotes something beyond language and musical theory, something that is raw and intensely human.

Related article:

It is followed by another highlight, Ayni Œana, which sees Baba Ould Hembara paired with Badi Ould Hembara for a piece that shifts between call-and-response vocal passages and sections of unhinged psychedelia driven by guitar and percussion.

Kweli Ould Seyyid’s guitar wizardry over boisterous percussion on Wezin is also worth a special mention, while his fiery collaboration with Kleyhid Ould Meyli at one point breaks down quite delightfully into a fit of laughter from the audience. It is a reminder once again that listening to music is at its best when it is done with others and not in isolation.