LanXess workers strike against exploitation

Striking Numsa members at Rustenburg’s LanXess chrome mine will not budge until management has addressed profiteering, corruption and sexual harassment.

Author:

10 March 2020

More than 1 000 members of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa) in permanent and contracted work at LanXess Chrome Mining in Rustenburg, North West, have been striking since 13 February 2020 against corruption allegedly taking place at the mine.

In a statement released on 6 March 2020 Numsa said the workers demand outsourcing, safe working conditions, a democratised workplace, true transformation, an end to corruption and nepotism and a living wage as “contractors and labour brokers only deliver sweatshops conditions”.

Related article:

Boyboy Mokete, 39, was a contracted employee at the mine. In October 2019 his employment was terminated. While employed, his payslip reflected all the statutory deductions, including payments towards the unemployment insurance fund and his provident fund.

When his contract ended, Mokete went to the Department of Employment and Labour in Rustenburg to claim his unemployment benefits. He was told his deductions weren’t reflecting on the system and the contractor had not been registered with the department – meaning his deductions had been stolen.

To date, he has not received any benefits. “I want my money. I want to support my family. I have to look after my children and want to see them with a bright future,” Mokete said.

When New Frame asked LanXess about the unregistered contractors, the mine’s corporate communications manager, Benjamin Marais, said, “LanXess verifies all contractors, prior to appointing them for work and to ensure that all procurement requirements are met. This process involves ensuring that the contractor is a legal entity.

“We ensure that they have a letter of good standing from the Department of Labour, and they have a tax clearance certificate from Sars. While this is the case, it must be noted that contracting companies are independent legal entities that are responsible for their own statutory requirements and should be held accountable if they don’t fulfil these requirements.”

Mokete’s situation is allegedly something many workers experience at the mine.

Sexual harassment

Ending sexual harassment and punishing perpetrators is at the core of the workers’ demands. “When a security manager who sexually harassed a woman employee was found guilty, management took no action. Our members had to embark on a sit-in last year in order to force management to take action … To date, this security manager enjoys special leave,” the Numsa statement reads.

Related article:

Thabo Nsoku, a mine overseer at LanXess, is accused of sexually harassing Katlego Mogwera. Presiding officer Tanya Venter of Tokiso Dispute Settlement, an independent commission appointed to adjudicate on the matter, found Nsoku guilty. Numsa members say the mine hasn’t informed them of any developments regarding Nsoku, yet Venter ruled that he “must be dismissed with immediate effect”.

According to Venter’s report, Nsoku “was in a position of power and overtly abused this. He did this in the case of women who were three positions junior to him. The seniority of his position is an aggravating factor. Mr Nsoku has not shown any remorse for his conduct … The company has an obligation to ensure that the work environment is safe for all employees, particularly vulnerable employees such as women. [His] presence at the workplace is a threat to a safe working environment.”

New Frame asked why Nsoku hadn’t been dismissed, but the question went unanswered.

Avoiding the sit-in

The Numsa statement reads: “This current sit-in could easily have been avoided. When the CEO was approached by shop stewards, he unceremoniously frogmarched them out of his office. In no uncertain terms, the CEO told shop stewards that he was not going to listen to them.”

Numsa general secretary Irvin Jim said: “I spent Sunday 23 February trying to persuade [LanXess] management to behave reasonably and fairly. Their failure to deal with worker frustrations is no different to throwing fuel on a raging fire.”

Lucy Bessit, 30, a contracted worker and a shop steward who was underground from 18 February until 5 March, said the mine bosses tried three strategies to dissolve the strike. “At first, the mine said there will be load shedding, but we continued to stay,” Bessit said, adding that the mine also paid them only half their salaries for February.

“Our payroll closes on the fifth of every month but on the 25th of February they paid us half salaries, and it is only Numsa members who received half pay,” claimed Wiseman Tabane, 43, a Numsa shop steward at the mine. “[The days when we started the strike] were supposed to be deducted [off] the month of March. This … made the comrades … angrier because we are fighting corruption, and now this happens.”

Bessit added: “On the third day [the mine bosses] agreed that our comrades who are outside [could] send food until 27 February. They even sent a report that they will not give us prepared food. They will give us [food sachets called] phakamisa because their so-called nutritionist or doctor said that our food is making us sick. However, there’s no doctor that came underground to check on us.”

Marais said, “LanXess discovered on February 18 that an uncertain number of strikers illegally accessed the underground section of the mine … While this is the case, anyone who is in the underground section of the mine can access clean water, food, medical assistance [on the surface] and sanitary facilities.”

Numsa said it condemns the “management’s conduct in the strongest possible terms and demands the provision of fresh food to members prepared by us, the union”.

Workers remain underground

Thus far, more than 140 workers remain underground. Only a handful of them opted to come out after becoming seriously ill or struggling to endure underground conditions. “Underground is unhygienic and unhealthy. Ventilation is limited. Since we’ve been out, we’ve been coughing. Even the sun is affecting us,” says Matshidiso Labello, 40, who is a permanent employee.

“We’d received sanitary towels, but now the mine is only sending phakamisa, and they don’t care about other needs,” said Bessit. “We’ve got diabetic people [who] we left behind [underground]. People who are on chronic medication don’t have access to their medication.”

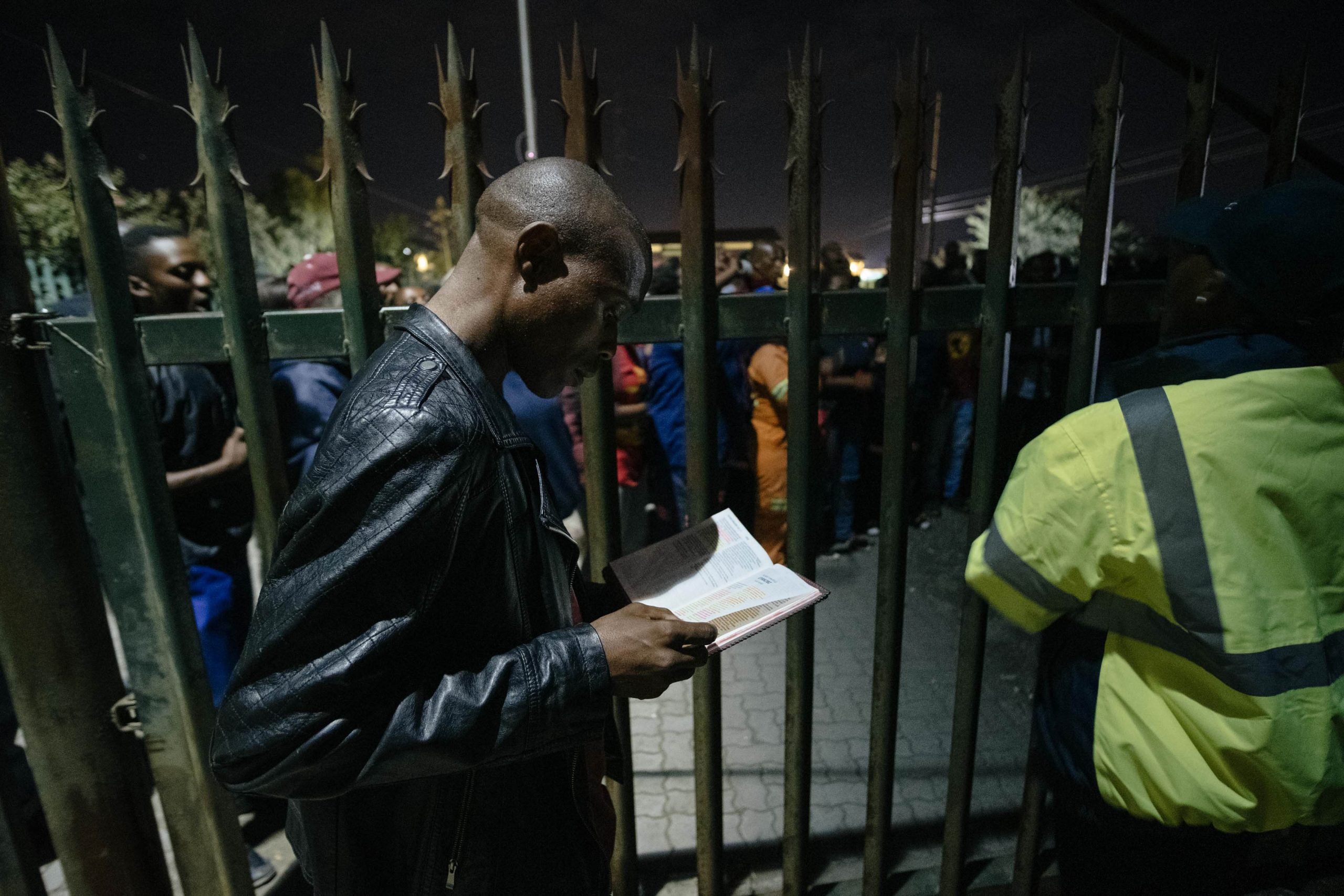

Hundreds of other workers are striking on the surface. But they have had to adapt to a militarised environment – they are being monitored by drones, surveillance cameras and security vehicles that ensure no one enters the mine’s premises. Only those wanting to exit the mine are allowed through the gates.

Production is at a standstill. Those locked within the mine’s premises are forced to fend for themselves. But loved ones, workers and family members who live close to the mine have become a support base. They cook breakfast, lunch and dinner for workers on the surface inside the mine’s grounds. The food is donated.

Blocked by a palisade fence

On the afternoon of Wednesday 4 March, Jane Segaxase, 35, accompanied by her best friend Tshegofatso Modise, 34, came to see if Segaxase’s husband, Tau Samuel Bogosi, 47, was okay. Segaxase came with her three-year-old last-born boy, Mojalefa, who got very excited when they walked up to the mine’s palisade fence. He thought he’d seen his father, but it wasn’t him.

Mojalefa is used to getting hugs and kisses from Bogosi, says his mother’s best friend. But, since mid-February, this hasn’t been happening. Mojalefa can’t touch or be touched by his father. Segaxase said Mojalefa asked her, “Why is daddy locked up in the prison of his workplace?”

“Unprotected strikes have an impact on the production of the mine as well as the wellbeing of workers who do not participate. This has been seen during the illegal underground strike that took place last year at the mine,” said Marais. “We urge that Numsa ends this illegal strike immediately as it places an additional burden on the mine’s economic situation.”

But the strike is far from ending if the workers’ demands remain unresolved.

In the meantime, Numsa will file an interdict at the Johannesburg high court to have access to its underground members and to get permission to give them food.