Killing the will of the village next to St Lucia Lake

KwaNibela residents rely on the fish and reeds they harvest within the protected iSimangaliso Wetland Park. But authorities consider this poaching, threatening the community’s lives and livelihoods…

Author:

19 January 2022

The fishing community in KwaNibela, northern KwaZulu-Natal, has raised concerns over conservation practices that have resulted in the deaths and arrest of the locals who fish on St Lucia Lake in the protected iSimangaliso Wetland Park.

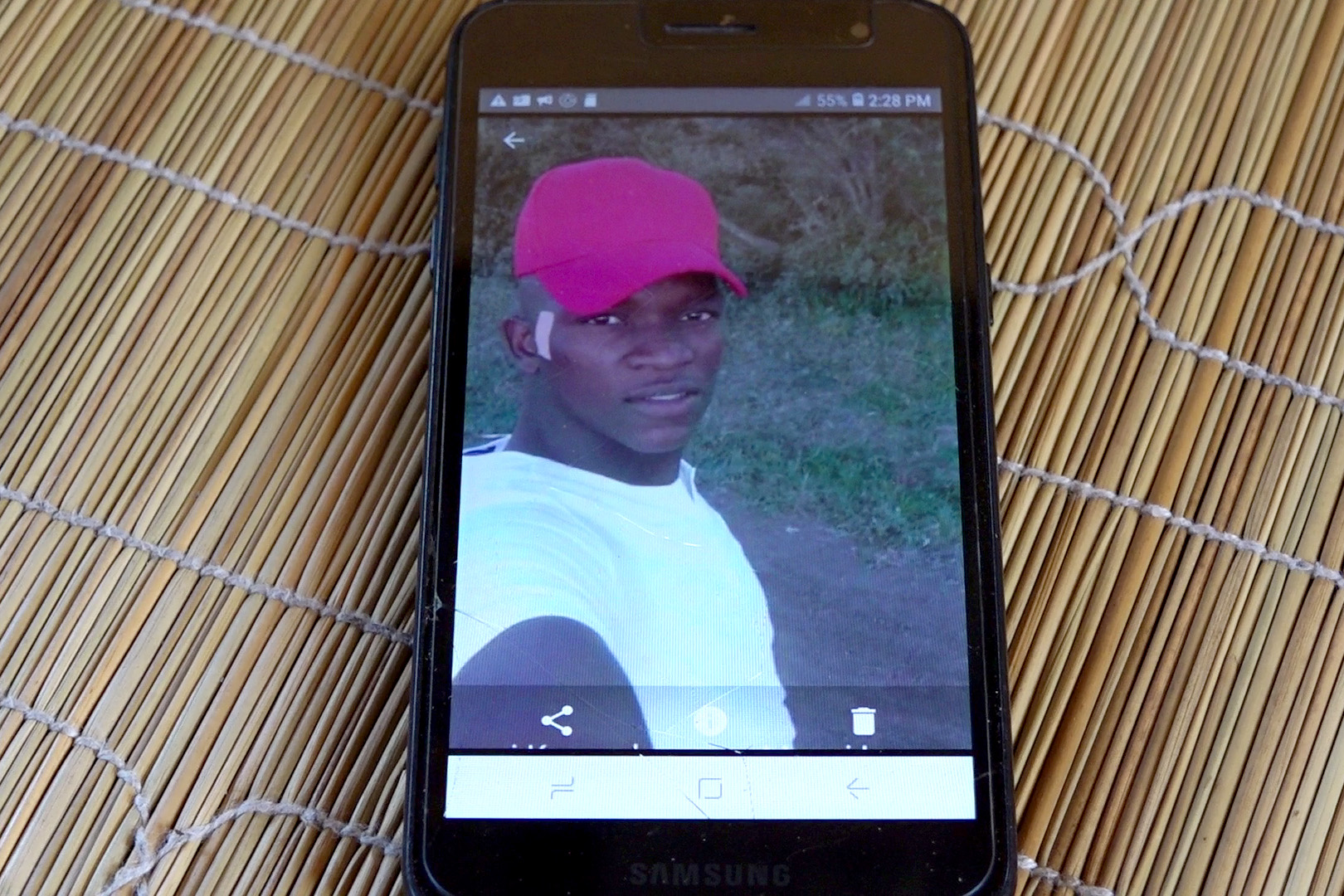

Fisherman Thulani Mdluli, 25, has been missing since 12 November 2021. He is presumed dead after allegedly being shot. This has left the community outraged. iSimangaliso Wetland Park describes Mdluli as a “suspected poacher, still missing”. Rangers allegedly shot and killed Thulani’s brother, Celimpilo Mdluli, on 16 September 2020 while he was out fishing with two others.

The community says the park’s regulations that restrict gillnet fishing and the harvesting of reeds are denying them a livelihood. This has caused tension between iSimangaliso, a conservation group, and the residents, who use the lake for subsistence fishing and reed harvesting as well as crop and livestock farming.

The community claims iSimangaliso has done little in terms of engagement and participation with residents, which has created a complex and conflicting relationship between park authorities and those who live in KwaNibela.

Field rangers on duty on 12 November heard a gunshot and on investigation “observed four poachers” approaching two boats, iSimangaliso said on 16 November 2021. One of the poachers “unexpectedly started shooting at the rangers … The field rangers returned fire. When the shooting ceased, the field rangers moved towards the boat [from which] an armed poacher had fired shots,” said the statement. “Rangers … observed blood in the water, which made them suspect that one poacher, probably the one with a gun, had been shot. He might have attempted to avert arrest by jumping into the water.”

The need for closure

“The tears have dried. We have none left,” says Fundisiwe Mdluli, Thulani’s aunt. “Losing Celimpilo left a deep scar in our hearts. It’s like hitting someone on a stitched wound. We’ve barely made peace with his death, now his brother is also gone. The youngest son in this family.”

Fundisiwe unwraps a plastic bag holding Thulani’s green and red sandals. She says before he disappeared, Thulani planned to extend his one-room bedroom using bricks his brother gave him. Next to the shoes wrapped in plastic is a candle with wax melted thickly on its holder. It has been burning since Thulani’s disappearance. A new candle will be lit at dusk.

After the search for Thulani came up empty, Fundisiwe says, the family asked the induna and the police for permission to search for him in the lake. “The police agreed to take us on a boat to the scene of the incident, and this was the same spot that many of the fishermen use to park and hide their boats offshore while they prepare their camping spots. Usually they make fires to cook and keep warm. When we arrived, we got out to pray at the scene. We were then surprised to see that all the boats had been set on fire. When we questioned this, it became a heated incident and so the search was over.”

Fundisiwe says Thulani travelled to find fish with three neighbours on the day of his disappearance. He wanted to make R200 from fish sales, so he could buy water from the water truck to build himself an extra room.

Water is a scarce and often unaffordable commodity in KwaNibela. Residents say they have been without clean drinking water for years. This has forced them to rely on the nearby river, rain or water trucks, which cost them up to R600 a tank.

Fundisiwe occasionally leaves the rondavel to check on her pots cooking on the fire in another room. Seated next to her is Thulani’s mother, who cannot speak without crying and breathes shallowly. Over and over, she gathers herself, but grief and anger overcome her.

They can carry on with their lives only when Thulani’s body has been recovered and buried, says Fundisiwe. The bereavement custom in the family takes up to seven days, including two days of vigil while waiting for the body to return home for the burial and a cleansing ceremony after the funeral. While they wait, the fishing that helps sustain most families in the area has also halted. “We have run out of food now. We have been mourning for more than two months and that’s not normal. We are stuck here. We can’t even go to the lake anymore because our son’s body and soul is still adrift. The lake that made us who we are today has now been turned into a tool to kill the will of this village. We are nothing without that lake.”

The community’s livelihood – fishing and reed harvesting – dates back centuries. But Fundisiwe says that their way of life has been squeezed by shifting conservation regulations and climate change, making them uncertain about their future living beside the lake.

“There was a time when fish in the lake were in abundance; we didn’t need any nets. We would often use our hands to pick up the fish. Everyone’s belly was always full. The children never went to school or bed hungry. When the nets were introduced to us, we were happy to use them. Today we are surprised that we are now called criminals. We have lived in harmony with nature from information passed on through generations. We know not to harm nature. We appreciate the value of the lake,” she says.

Legal recognition

Women play a significant role in products manufactured from the grass drawn from the lake. Although it is men who manage the fishing, they often sell the fish to women who in turn sell them cooked at the nearby market in Hluhluwe. Women predominantly practise grass weaving, but gathering grass is difficult, requiring teamwork with the men. Nonetheless, women are at the centre of the economic and cultural thread of the community, which they weave into place.

KwaNibela has been part of a long battle for the recognition of small-scale fishers. The government finally recognised 106 fishers in 2019 and gave them rights to fish under South Africa’s Small-Scale Fisheries Policy of 2012. They now operate as a cooperative. Despite the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries giving it legal recognition, the fishers say there has been a lack of clarity regarding the rights to and regulations regarding the lake’s resources.

The Oceanographic Research Institute along with Bruce Mann from the South African Association for Marine Biological Research recommended the implementation of a small, legal, subsistence setup in 1995. But compliance and sustainability issues led to the gillnet fishery failing three years later, and the experiment was ended. Since then, gillnetting has continued illegally. KwaNibela fishers are harvesting with permits in terms of the Small-Scale Fisheries Policy, but illegally in terms of the Marine Protected Areas regulations.

Wilmien Wicomb from the Legal Resources Centre says that while iSimangaliso’s mandate to protect the lake is important, it lacks clarity and balance and fails to acknowledge the customary rights of the fishers. Wicomb says it is important to unpack the violent behaviour of the rangers in an attempt to unravel these recent cases, which are increasingly going cold.

“What should happen is that whenever the state wants to regulate the customary rights, they need to first identify the customary rights that exist in the area and weigh it up against the environmental imperative they have, and communicate that with the people, instead of ignoring those rights as if they don’t exist. That’s blatantly unlawful,” Wicomb says.