Jazz original Malcolm Jiyane plays it forward

The multidimensional trombonist goes beyond tradition, experimenting with form and genre in his fresh and distinctive five-track album Umdali.

Author:

17 November 2021

For a while, musician Malcolm Jiyane was the worst-kept secret in jazz.

He had been on the radar of serious fans for close to 10 years, first as a fearlessly original teenage trombone voice from the Music Academy of Gauteng in Benoni and then on voice, bone, piano and canvas – he’s a visual artist, too – at Steve Kwena Mokwena’s Afrikan Freedom Station in Westdene, Johannesburg. He rapidly gained respect, including from older jazz peers such as bassist Herbie Tsoaeli, who featured Jiyane on his African Time album. But that very originality meant less space for his kind of music on big commercial platforms such as festivals.

That has changed, though. In 2020, Jiyane led the Spaza ensemble, improvising the soundtrack for Soweto Uprising documentary Uprize, which drew significant international attention. In the week we talk, they are putting together a video for the Le Guess Who? festival in Utrecht. And on 12 November, his debut album as leader of the group Tree-O, Umdali (the creator), launches on vinyl.

Jiyane was born in Benoni, into tough family circumstances. He spent time at Kids Haven, a home for orphans and other children in need, in his early teens and it was there that he encountered the late trumpeter, activist and music school director Johnny Mekoa. Mekoa brought the big band from his Music Academy of Gauteng to Kids Haven to play, hoping to recruit any child with an interest in music. Jiyane has recounted many times how he felt when he heard the band play Bags’ Groove: “And my hair stood up on end.”

After hearing Mekoa blow, Jiyane wanted to study the trumpet. But Mekoa “found out that I smell of cigarettes” and warned him off, saying smoking was bad news for the lungs of a horn player. Still, the teenager’s interest in brass instruments persisted “and there was a friend of mine studying trombone at the same school, and also staying at Kids Haven. He was lazy to practise, and during the weekends when he’s not around, I’d pick it up, open it and try to do what I’d observed him doing. From that time, I’ve never looked back.”

A long time coming

Jiyane’s long-term relationship with the Afrikan Freedom Station helped bring about Umdali. Mokwena, the founder of the cultural and gallery space, wrote the sleeve notes for the album. In those, he recalls how Jiyane and his outfit Tree-O made their debut when he first opened the venue in 2012. Jiyane returned, even after that first show bombed, and the two of them worked patiently through often disappointing door takings to build an audience. Tree-O was still appearing – by now a strong crowd favourite – when the venue closed to relocate in 2019.

Mushroom Hour Half Hour (M3H) label co-founder Andrew Curnow says they were finalising a new Tree-O album in early 2021 when sound engineer Peter Auret told them he already had a full Jiyane album on his hard drive, recorded in 2018 at a session facilitated by Mokwena.

“The first track he played us was Umkhumbi ka Ma. We were gobsmacked! [Although] the recordings were raw and hadn’t yet been mixed, they sounded great. We all immediately knew we had to put this music out before the album we were [currently] recording.”

Curnow describes the rush to edit, mix and send Umdali for mastering within three weeks. What’s more, he says, the label is busily searching for other unreleased Jiyane material.

There’s no predicting what that will be. Although Jiyane’s musical passions began with jazz, they now extend into every genre, from folk music to classical and avant-garde. “I believe there’s still more uncharted waters,” the trombonist says. “Just like the universe, we’re still discovering new stars. So, art is also a never-ending story.”

Between tradition and innovation

Umdali has only five tracks, each carefully chosen from Jiyane’s multiple compositions, he says, “to work with the artists I had at hand” and pay tribute to figures who helped shape his life and music. What makes all the tracks so intriguing and distinctive is the way the leader walks an edgy musical line between the South African jazz tradition and innovation.

M3H label co-founder Nhlanhla Masondo says Jiyane neatly escapes what he calls “the trap” of South African jazz. On the one hand, the voice of the music is unique and its quality instantly recognisable, even if both are difficult to pin down in words. On the other, some musicians try so hard to capture that distinctly South African sound “that they end up very… cornball. The music ends up banal and unoriginal. Sure, it’ll stand out for its national character, but it’ll be totally wack … [But] in Malcolm’s case, you can hear the long line that this music comes from and continues … It’s at once ancient and brand new.”

Masondo says Jiyane’s originality, which is rooted in the South African jazz tradition, is “ancient, because the lineage is unmistakable … These are South African grooves. Yet the sounds are as fresh as the Jazz Epistles or Heshoo Beshoo or Batsumi must have sounded when they came out. The music doesn’t stay in some amorphous South Africanness but clearly belongs to Malcolm, who is South African, and his colours happen to show.” As Jiyane puts it: “As an artist, you are always shaped by your space.”

One place where the lineage sounds particularly loud is in the tribute track, Ntate Gwangwa’s Stroll, written for the late Jonas Gwangwa who had been among the first patrons of Mekoa’s school. “When I started wanting to know more about trombone players,” Jiyane says, “most masters of this instrument I studied were from overseas: JJ [James Louis] Johnson, Curtis Fuller, Albert Mangelsdorff and so on.

“But then I started searching what this continent has in terms of jazz trombonists and I came across Bra Jonas. His music blew my soul apart.” Jiyane recalls hearing Gwangwa’s Flowers of the Nation as another spine-chilling moment in his musical journey. “From then on, I knew I had to study him. As a trombone player, composer and arranger I hold him close to my soul. I believe in his music, it speaks to me in a language that is my source of life.”

Ntate Gwangwa’s Stroll evokes the deliberate, bluesy solos and call-and-response conversations with the band that Gwangwa employed in his own compositions, including a perfectly in-period trumpet contribution from Tebogo Seitei. “I dedicated this song to [Gwangwa] purely because of the beauty I found when I listened to his music,” says Jiyane. “I love him.”

Moving music forward

He goes on: “There is a Zulu saying, indlela ibuzwa kwaba phambili (it is always best to seek guidance from those who have walked the path before you). So, that whole generation of Bra Jonas, Bra Johnny, is a source of knowledge … Studying their archive enables you to create your own.”

The sense of mission that Jiyane admired in Mekoa continues to give him direction in his life. “My schooling ended at grade 6, as my grandmother couldn’t afford to take care of all [my] siblings alone. Without Bra Johnny, there wouldn’t even have been a music school in Daveyton township.” The lack of outlets for creative expression in impoverished areas “hurts deep inside my soul, because it’s still happening in 2021”.

Related article:

One of Jiyane’s dreams is “to use what’s inside me, this gift, to create change in our country … I’d love to open up a music school in KwaMhlanga in Mpumalanga, where my mother lives. Every time I visit that place, I’ve observed how deprived and bored the youth are. No recreational facilities, no libraries, nothing. After all, I wouldn’t even have become a musician if Bra Johnny hadn’t reacted to his calling to do something.”

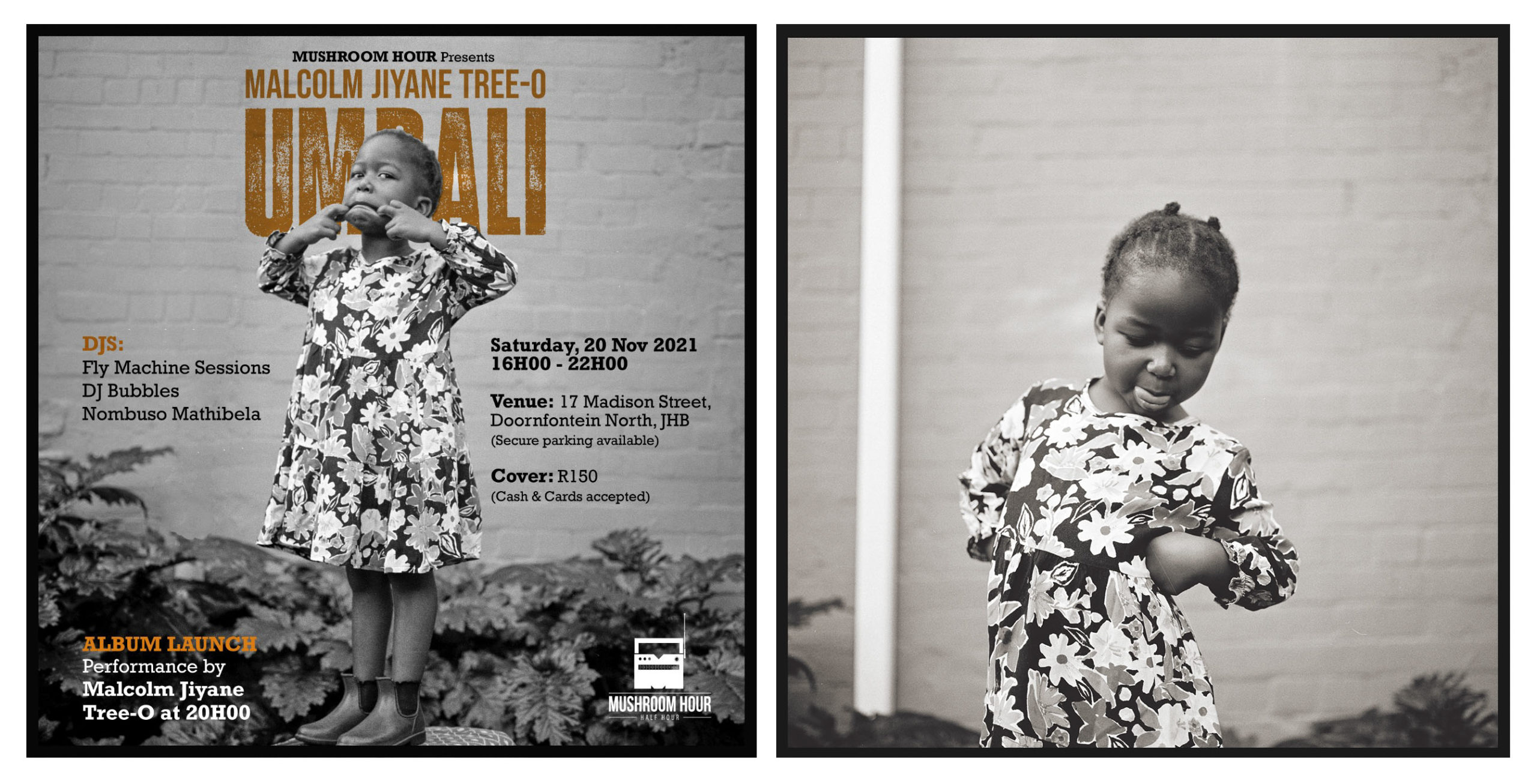

Malcolm Jiyane’s album launches on Saturday 20 November at 4pm at 17 Madison St, North Doornfontein, Johannesburg.