Jacob Dlamini, ‘relentless detective’ of the academy

The historian speaks about the multiple histories of Black experience under apartheid and the myth of the omnipotence of the authoritarian state.

Author:

4 August 2021

Jacob Dlamini is the enfant terrible of South African historiography. His quartet of books has comprehensively questioned the shibboleths and axioms that inform the writing of the social history of modern South Africa.

Native Nostalgia (2009) raised the question of leisure and the life of the mind of Black people under apartheid. Askari: A Story of Collaboration and Betrayal in the Anti-apartheid Struggle (2014) dealt with the politically sensitive question of Black collaboration with the apartheid regime. His most recent work, breezily titled Safari Nation: A Social History of the Kruger National Park (2020), enquires into the history of Black tourism in Kruger Park under apartheid, raising fundamental questions about Black histories of travel.

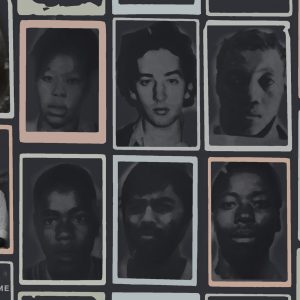

He is a creature of the archive, a relentless detective among dusty files, searching for the buried fact and the contrary story. This is evident in his wonderful work Terrorist Album: Apartheid’s Insurgents, Collaborators, and the Security Police (2020) which enquires into the existence of a photo album maintained by the apartheid secret police on its political enemies. The book questions the seeming omnipotence of the apartheid state, by looking at how much fear, fantasy and fancy underlay official knowledge.

Related article:

Dlamini began his career as a journalist in South Africa and then went on a scholarship to study political science at Yale. He was less than enamoured of the procedures of the American political science establishment, premised on producing neat arguments with a few variables. Safari Nation is based on his doctoral dissertation submitted to the Yale history department.

The motto of the Royal Society, perhaps the world’s oldest scientific institution, is “nullius in verba” or “take nobody’s word for it”. Dlamini’s rugged scepticism towards conventional truths means that he occupies a special place in the new generation of writing about South Africa. In this interview with Dilip Menon, Mellon Chair in Indian Studies at the University of Witwatersrand, Dlamini speaks about his work and historical practice.

Dilip M Menon (DMM): Your body of work, from Native Nostalgia to Safari Nation, has a consistent thread running through it of thinking against historical axioms. Your first book worked with questions of the life of the mind and leisure among Blacks under apartheid, questioning the existing narrative of a life of exploitation and immiseration alone. Your most recent takes up the question of Black tourism in the Kruger Park in the same period, thinking with the Black middle classes and the question of leisure. Your historical work seems to possess a political as much as an aesthetic thrust. Could you tell us about your philosophy of history, if that’s not too grand a proposition?

Jacob Dlamini (JD): Not at all. I do not have a philosophy of history as such but I do, at the most elementary level, take seriously the notion that history is about the study of change over time. It is about becoming; about how individuals and communities become who and what they are; about how ideas, countries, places, systems, things become what they are; and about how that process of becoming changes over time.

To be sure, the idea of history as the study of change over time is not some innocent label that can be attached to any work concerned with the past. But it does (or should) at least focus the mind on the only historical axiom worth thinking with, namely that change is the only thing in life that does not change.

DMM: Postcolonial theory after Edward Said has worked with the implicated ideas of power and knowledge. The “native” appears like a fly in amber, trapped within multiple intersecting narratives generated by colonialism, apartheid and so on. You write about Black historical agency; in fact, that is the central theme uniting your works. Do you see yourself as reacting against postcolonial theory?

JD: One way to think about the importance of Edward Said’s work – and, of course, the richness of Said’s work is such that there is more than one way to approach it – is as a timely and ethical injunction to remember always two things about the so-called native. The first is that the native has always had agency; the second is that the native has always been present and active in the process of her own making as a historical agent.

This injunction has served scholars of the postcolony well. It has, for example, given them the conceptual tools to deal productively with the role of contingency in the making of the native as a specific historical type – common to all places marked by the imperial and colonial encounter, yet also unique to wherever that encounter took place.

More importantly, Said’s injunction has bestowed upon us a historical sensibility that manifests always as a search for complexity. But – and this is where I see myself asking postcolonial theory to do more than help me remember that context and contingency matter – we are long past the moment when we had to begin every postcolonial move by pointing to the complexity of native life. We are long past the stage where we had to begin by showing that the native had agency. As Lynn Thomas reminds us, agency, too, has a history. Our job is to explore that history. That is what my books seek, each in its own way, to do.

Related article:

DMM: Following on from this, your works stress a return to the state’s archives even as the profession moves towards a more philosophical engagement with questions of space and time. Do you see the archives as central to the historian’s enterprise?

JD: Like all well-schooled scholars of history and of the postcolony, I am suspicious of the archive, especially the colonial and apartheid archive as institutions. But I must confess that, like most well-trained historians, I cannot help but feel a positivist frisson in my body each time I find an item in the institutional archive. This might be a document, a photograph, an audio or a video clip that helps me understand something of the past. Of course, the relationship between whatever archival sliver I find, and the past is not one of a direct correspondence. There is no one-to-one relationship between archive and history. There is too much mediation (by state officials, archivists, private individuals, termites and other elements, etc) for that to ever be the case.

But the archive broadly defined is absolutely important to the historian’s enterprise. Not as a repository of the truth, not as an innocent arbiter of conflicts over the past – those are fallacies. But as one site (not source but site) among many for the working out of historiographical disputes about the past. As Verne Harris puts it, archive is what archive does.

DMM: One of the axioms that you resist is the binary division of white and Black, the enforcer of apartheid and those fighting for liberation. You raise the controversial question of the Black “collaborator” in your book Askari, through the figure of Glory Sedibe. What prompted this enquiry, shattering a shibboleth of nationalist narrative?

JD: It all goes back to my political biography. I grew up in the student and youth movements against apartheid. I grew up politically in the Congress of South African Students and the Katlehong Youth League (this was before the unbanning of the ANC and its Youth League). I came of age politically doing ideological and intellectual battle with members and supporters of the Azanian People’s Organisation, the Pan Africanist Congress and the Trotskyist Marxist Workers’ Tendency.

Looking back at this phase of my life, I am struck by how intolerant I was. I was so certain that we in the ANC-defined Congress tradition were right and that history was on our side. Imagine my surprise, then, the first time I read about Glory Sedibe, a highly trained and senior member of the ANC’s military wing, who had not only defected (or so the security police and the initial newspaper reports said) but had gone on to work actively and with some enthusiasm for the apartheid state. “How could this be?” I wondered. And so began my obsession with Sedibe. As I now know, Sedibe did not defect; he was kidnapped. Yes, he worked for the apartheid state. But the story of how he became an apartheid assassin was more complex than I had imagined.

Related article:

DMM: A central concern in your work has been that of questioning the idea of the overwhelming power of a state or an ideology. There are always cracks in the edifice and the indeterminacy of generating accurate surveillance. This is exemplified in your book The Terrorist Album where you stress the vanity of the idea of an apartheid panopticon. Could you tell us about the place of this book in your historical imagination?

JD: The Terrorist Album grew out of the research I did for Askari, my book about Glory Sedibe. I was struck by the confidence with which the former apartheid security police officers I interviewed for that book spoke about their work. I was amazed by the manner in which they invoked their so-called terrorist album, as if it were some sort of talisman that could, on its own, illustrate and explain their efficiency. That, of course, made me want to see, to touch and to smell this album. But that took some old-fashioned sleuthing and archival work as the police had systematically destroyed a significant part of their archive before the end of apartheid.

But, once I tracked down a copy of the album, I was stunned to discover just how inaccurate the thing was. Here was an object defined by apartheid’s obsession with race, yet its compilers could not always tell their whites from their Indians (and here I am using apartheid nomenclature). When I confronted the ex-police officers about this, they blamed their former victims (especially their former African detainees) for being incapable of distinguishing between Indians and whites. The ex-cops would not accept that race was not the fixed category they believed it was.

But the book is about more than these agents of racial panic. It is also about the nostalgia for the apartheid order as somehow efficient and ordered. Apartheid was neither efficient nor ordered.

Related podcast:

DMM: To come back to Safari Nation, apart from the history of Black travel and leisure, you point to larger histories of movement and migration. What do national borders mean in Africa and more important, how can we move beyond narrow national histories? Do we need to?

JD: Mobility is absolutely key to struggles for Black freedom. Think of Mohandas Gandhi and the train in Natal, Paul Robeson and WEB Du Bois and the official cancellation of their passports in the US, and the dompas and the millions of Black South Africans who had to carry the thing to live. This is not an exhaustive list, for sure, but struggles for Black freedom have always been connected intimately to the fight for the right to get around.

As Arjun Appadurai points out, the idea of the native was premised on the claim that the native was rooted in place, that natives did not travel and that they existed on the margins, if not outside, of history. Black freedom struggles have been a sustained rejection of this idea. No wonder we speak of Black political groupings as movements.

Safari Nation explores what, for the Black elites in South Africa, this right to move entailed. But, certainly in the African contexts, borders came to assume great importance as markers of sovereignty. Recall one of the key tenets in the founding charter of the Organisation of African Unity: thou shall not tinker with African borders, be they colonial impositions or not. But the actual and imaginative movements of the people we study are such that methodological nationalism can never do justice to their stories. South Africa has no prehistory as such, meaning as a place called South Africa. There was never a time when only so-called Africans counted as South Africans. South Africa was born ethnically and racially mixed. We have to take this seriously as a historical fact. There should be none of that “I came first, you came last” nonsense.

To the extent that South African history is different from, say, Zimbabwe’s history, yes, borders matter. To the extent that the political economy of South Africa is, in fact, the political economy of Zimbabwe, no, borders do not matter. Our scholarship must reflect this.

DMM: A last question. What motivates your choosing of a problem to write on? Are you a contrarian by temperament?

JD: I aspire to being a storyteller. I am drawn to stories that are ignored or that are often taken for granted. That, for me, is what history is about. It is about telling stories that not only illuminate some aspect of human life but that help us see the interplay between change and time. Am I a contrarian? I don’t know. I know that I am not a joiner, for sure. I am suspicious of settled truths; I baulk at certainty. As Brenda Fassie, South Africa’s unsung sage, says in one of her songs: Umuntu angeke um-confirm-e. You can never confirm a person. People are always this, that and more. They are never just one thing.