‘It’s not the notes, it’s how they’re played’

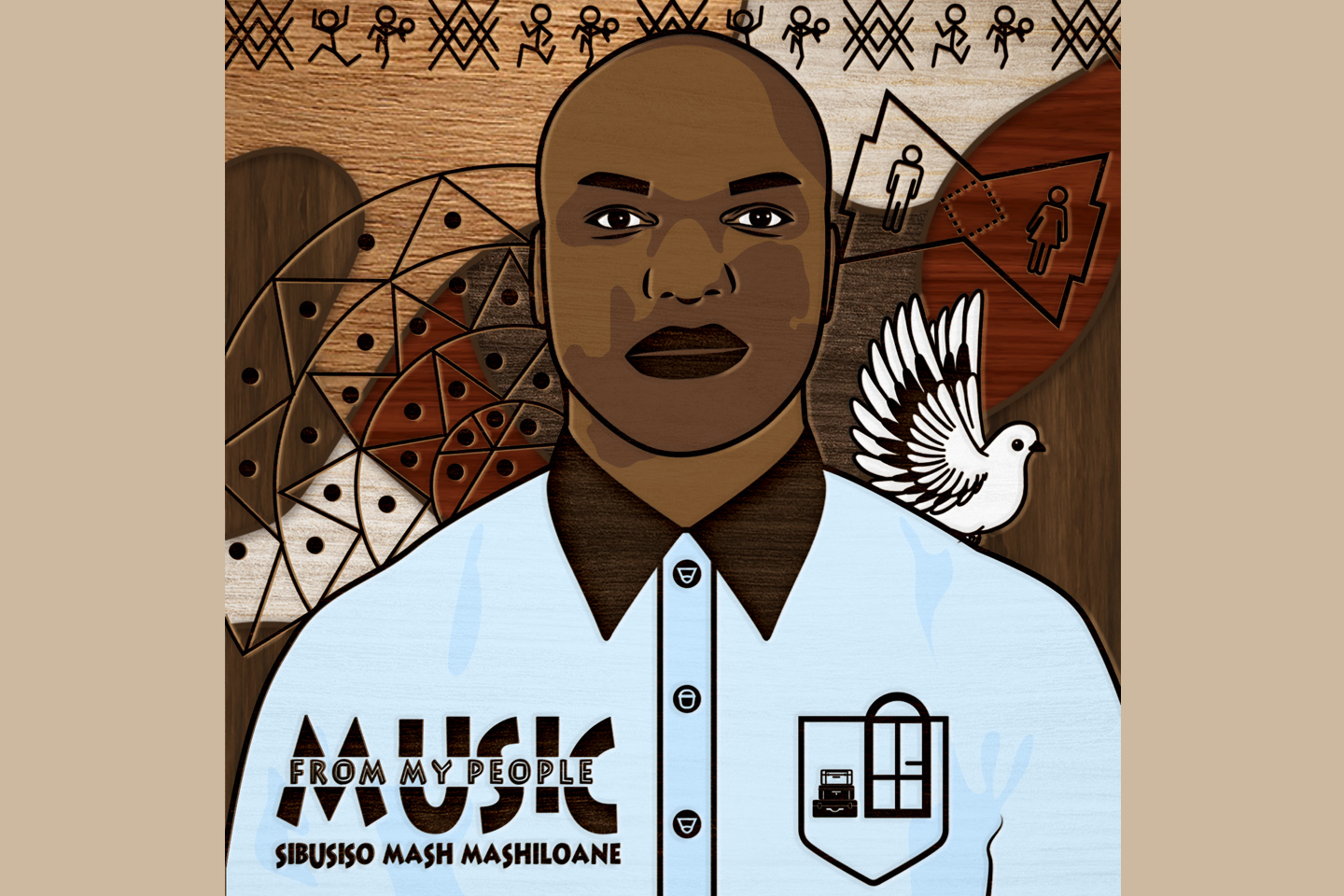

Pianist Sibu Mashiloane’s new album enacts the collective dance of South African jazz. It is his sixth album in six years, and a work of many trusted hands.

Author:

28 January 2022

Setting goals is one thing; meeting them sometimes another. But pianist Sibusiso “Mash” Mashiloane vowed in 2017 he would release an album a year until 2023 – and number six, Music From My People, has just landed. Conceived on a much grander scale than its predecessors, it involves 17 other musicians and brings together his music praxis and the theoretical insights his academic research into the identity of South African jazz is mining.

But that doesn’t make the music abstract. Because, for Mashiloane, musical identity is embodied in people: in their songs, dances, struggles and communities. “It’s not the notes – everybody on the album had the same notes. It’s how the notes are played … the music is a carrier of shared humanity.”

Some of the album’s 10 tracks have been in development since 2019. It was then, performing at the Sauti za Busara festival in Zanzibar, that Mashiloane’s thematic vision crystallised: “There were people from everywhere, all embracing music. It’s nothing to do with geography; the important narrative is social equality – ubuntu.”

Related article:

It was necessary, he says, to capture that vision in the album’s process as well as in the melodies. “The ensemble has to be a community. ‘My people’ for this album come from all walks of life, but they all share similar shades of ubuntu. As well as KZN [KwaZulu-Natal], we have Cape Town [bassist Shaun Johannes, guitarist Keenan Ahrends and reedman Buddy Wells], the Eastern Cape [vocalist Xolisa Roro Gqoli-Dlamini], the Black community in the US [drummer Billy Williams] and Bra Khaya Mahlangu representing Soweto.”

Personnel deliberately spans generations as well as geographies. Alongside Mahlangu is veteran percussionist Tlale Makhene and guitarist Bheki Khoza. “They’d tell me amazing histories of their heroes, of people singing and dancing in train stations during the struggle. There’s something special about that generation.” But the sax line also includes one of the instrument’s youngest rising stars, Linda Sikhakhane, and two vocalists close to the start of their careers: Wandithanda Makhadula and Nomthandazo Madiya.

“For me,” says Mashiloane, “what mattered was, were they able to give me the language of how our people would have danced.”

Dancing, singing, listening

That concept of South African jazz as embodied practice is central to Mashiloane’s work. “We work from our pulse. You connect with the vibrations of your body and then you take it out. You must first learn how to dance, then reflect on that and you can play it. I used that idea a lot rehearsing in Cape Town, where the young UCT [University of Cape Town] musicians were coming new to the music. I’m not a charts person – charts are just a reference … so, [to get the feel] I’d say: let’s dance to it.”

As dance, so song. Female voices are central to many of the arrangements. “At home, we sing – and we sing out! So that’s another characteristic of South African jazz: once you start talking ‘my people’ it starts from the actual human voice. In history, sometimes we only had the voice. Playing an instrument is one remove from that.

“I can’t sing, but I can hear the voices in my head. Wandithanda, from an isiXhosa background, who was most in the studio with me, was really good at interpreting that. Nomthandazo brings a smoother sound and elements from Zulu tradition, while Xolisa’s voice has a more mature, characterful edge that makes a tune like African Communal sound more real. On [the album] Closer to Home the voices I used had more of a [male] initiation school vibe, but this one really needed women.”

To determine whose sound a particular composition needed, Mashiloane spent a lot of time “going to other people’s gigs and just listening”. That helped him decide, for example, that the track Sabela Uyabizwa needed a guitar sound with “that rootedness of rhythm and musical intellect” Khoza could bring, whereas Freedom Day “needed a more contemporary touch and the texture of effects, so that was Keenan”.

The musicians brought more than their character. Mashiloane says he was blown away by the generosity of his co-players with time and ideas. “When I went to Joburg to record Tlale’s parts, for example, he’d arrived at the studio an hour earlier and had already developed one track.”

The life communal

Other features of the South African sound the album showcases, says Mashiloane, include the groove of its “lyrical basslines”, which he foregrounds on Omalume. “And our harmonies and melodies are never conclusive. We’re used to doing things in a more communal way, where collaborators come in with how they feel it at the time. They can do that because they’re not confined by music theory but are all carrying similar life experiences.” He alludes to that approach in the “Zion feel” of Beyond Words (WeBlues), where “like in our churches you’ll hear humming [from the congregation] coming in at different points”.

While the track Umagoduka may prompt listeners to think back to Zim Ngqawana’s Migrant Worker Suite, Mashiloane’s inspiration is different. Ngqawana’s composition offered respect to the migrant miners of his home province; Mashiloane is referencing other themes. The music alludes to the restless, hybrid urban soundscape of the Brenda Fassie era, “and to those people we all know who can’t settle and are always on the move. In the bigger narrative, it’s also about removals and displacement”.

Related article:

Displacement shadowed the project too. Covid-19 restrictions meant not everybody could be together. Many of the parts were recorded by contributors at a distance. “I’m so grateful that in spirit and love for the music they were all able to join in the same dance.” Album No. 7 may revisit some of the same material live and together. “Like in this conversation,” Mashiloane says on our Zoom screen, “when you’re face to face, the thinking processes are different and the directions less predictable.” He’ll also reinstate the leg rattles he often wears while playing, absent on this cut, “to make it as acoustic as possible”.

That’s not the only way future plans are shaping up. Mashiloane’s fifth album released in 2020, the solo Ihubo Labomdabu, generated resources to make this sixth possible – for the first time in the series. In the same way, he hopes this one will contribute towards developing a home studio in his garage. “I hear so much talent in my classes,” says Mashiloane, who teaches at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, “that there must be a way for people to come and record their music. Funds from Music From Our People might help to record more music from our people.”