Italy’s regularisation laws a nightmare for migrants

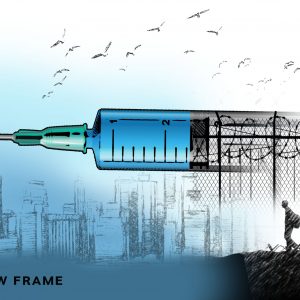

In a regularisation drive fraught with irregularities, migrants who work in Italy face an uncertain future as they struggle in applying for special permits that are arbitrarily issued.

Author:

12 April 2021

“I’m so happy that I got the residence permit. It was my last chance to get regularised,” says Kolo Konate*, 28, from the Ivory Coast after having successfully concluded his regularisation.

The happiness evident in Konate’s eyes could have been reproduced on the faces of thousands of other undocumented migrants who have been living in uncertainty in Italy for some time. But that is not the case.

More than eight months after the deadline for submitting the application for Italy’s last mass regularisation closed – on 15 August 2020 – the vast majority of applicants are either waiting for an answer or have encountered numerous difficulties. These range from not being able to submit the application at all to having to jump hurdles to do so.

“We organised some webinars to talk about the results of this regularisation, but we couldn’t come up with conclusions,” admits Marco Paggi, a labour law attorney and member of the Association for Legal Studies on Immigration (ASGI). “There is no case study, because most of the applications have still to be processed.”

Related article:

The regularisation drive has already faced many obstacles. First of all, it is selective. This means that migrants present on Italian territory before 8 March 2020, and have not left the country since then, could only apply in two circumstances.

In the first case, they could apply if they find an employer willing to hire them or who already employed them irregularly. And this is only applicable if they seek employment, or are already employed, in the sectors of agriculture, breeding and animal husbandry, fishing, aquaculture and related sectors. In the second case, they had to prove that they worked in these sectors before 31 October 2019. In the latter case, those who have obtained a residence permit, which lasts six months from the moment the application is submitted, can convert it into a work permit by exhibiting an employment contract in one of the aforementioned sectors.

Exclusions and irregularities

The non-inclusive nature of the regularisation, the long waiting period for the residence permit, including the difficulty of obtaining one after applying, led to the many problems around the country’s regularisation drive.

Excluding all other sectors of work has left thousands of people undocumented and without access to medical care. This is not a good result for a law that aims to “guarantee adequate levels of protection of individual and collective health as a consequence of […] Covid-19.”

“I have found many jobs, especially in car-wash workshops, but, unfortunately, they aren’t valid for the purposes of regularisation,” says Nisar Khan*, 30, from Pakistan.

Moreover, in cases where migrants have received a response, the bureaucratic delays resulted in some of them receiving the residence permit only one week before its expiry date or after it already expired. This left many in a prolonged state of uncertainty during the six months of waiting, to the point of affecting their mental health.

Related article:

Many of those who are still waiting for an answer also say that, in the interval, the employers they had found no longer had a need for them. This is because in the agricultural sector – the sector for which the regularisation was mainly approved – the jobs are seasonal and the employers needed employees for the grape and olive harvest between summer and autumn, not now.

“I feel really bad because I’d already have a job, but the documents don’t arrive. It’s difficult to cope with all this,” says 28-year-old Babacar Diarra*, from Guinea.

“This regularisation had to run out quickly, and Covid-19 has little to do with it, because these offices have always worked badly,” admits Paggi.

These exclusive measures have done nothing but fuel illegality in the sector, a problem the legislation supposedly aims to defeat. The drive actually failed to solve the labour shortage in agriculture. Only 30 694 applications, out of the 207 542 registered by December by the Ministry of the Interior, came from agriculture, which is roughly 15% of the total.

“This is nothing new. The willingness of farmers to hire regularly has never been there,” says Paggi, who handles numerous applications in Padua, in the Veneto region. Someone managed to get regularised by paying the farmer or his caporale (the man who selects a group of labourers). Basically, someone has decided to work for free for a certain period in order to get regularised.

Exploitation on all fronts

In some cases, the employers on whom migrants depend for regularisation demand money. The amounts can reach the order of thousands of euros too. This is what happened to Khan, but in the housework field. The pensioner who put him under contract asked him for €1 000. Unfortunately, many migrants have their backs against the wall. Applying for regularisation means having renounced the request for asylum. Therefore, if the regularisation does not succeed, they find themselves back to zero after months of waiting and hoping.

“What difference does the industry in which I work make? While waiting for the residence permit, problems were accumulating: health, money, future…,” Khan says.

“Also, the amount of applications for domestic work, which corresponds to about the remaining 85%, is distorted. Many real domestic workers have been left out,” Paggi continues. “This is because many people who work in sectors excluded from the legislation have found themselves without an alternative and have configured the application in the housework sector. Ultimately, limiting sectors has resulted in illegality and now those who applied for domestic work but already had another job in another sector are in trouble, because they should also work for the employer they applied with,” he says.

Related article:

This is exactly the situation Konate finds himself in. He was already working as a warehouse worker in the Swedish multinational IKEA but had to find a farmer to fictitiously hire him in order to apply for regularisation. “I’ll have to ask to reduce my working hours at IKEA, because I’ll have to prove that I also work for the employer I applied with,” says Konate.

All the migrants interviewed submitted their applications through the National Association Beyond Borders (Anolf) of Le Marche region. They are one of the bodies that manage the reception of migrants in this region of central Italy. However, the situation is the same in all regions. An article published in La Repubblica, on 7 February 2021, revealed that only two out of every 100 migrants received a reply. Only a few of the 142 applicants who made their submissions through Anolf got a response.

The organisation’s co-president Neli Isaj raises another point. “Many people couldn’t apply because they didn’t have the passport of their country or a document of the same value,” she says. “And their countries – especially African ones – haven’t made it easier for their citizens to obtain an identity document.” Isaj also cites other cases in which the embassies of African countries have allegedly hindered passport-application procedures and raised prices.

In many instances, migrants simply accepted these exploitative terms “because they don’t want to be undocumented anymore”. Some governments, such as Guinea, have even banned the issuing of passports abroad. Diarra had to use a consular card when submitting his application.

Why the delays?

As for the delays by the authorities in charge of checking applications – from the police to the labour inspectorate – Isaj says that they only processed applications sent between 10 June 2020, the start date, and 10 July 2020. This was in the province of Ancona as of 24 February.

“Authorities don’t give answers. The main justification is Covid-19. There is no effective explanation on the delays, also because no deadline has been set by law,” she says. These ambiguities are also the cause of possible conflicts between migrants and the associations they rely on. “It’s a frustration. We face suffering people who ask us for the bill because they have interfaced with us. We must always give timely answers, and this means putting enormous energy into making them understand the situation.”

The many associations set up to address migrants’ issues contend that authorities could have granted migrants a provisional health card, given the spread of Covid-19. “We have found a solution with some employers,” says Isaj. “They’ll hire even if the regularisation goes wrong, so the migrants can apply for the health card.”

Related article:

From the beginning, it was clear that this regularisation was badly formulated and that it would force some migrants into a corner, leading to them finding new ways through which they can be regularised. “[The] ASGI sent a letter to the government last April highlighting what was wrong, but we didn’t get any answer,” says Paggi. “I’ve experienced all the regularisations in Italy since 1986, and what I can say is that it got worse and worse. History should teach, but politicians have learned nothing in 35 years.”

According to the previous government that passed the law, the 2020 regularisation should have affected half of the around 500 000 undocumented migrants who are based in Italy. Paggi predicts that it will only affect about 100 000 of them. “There is a huge gap between those who make the laws and the people who face reality on the territory,” concludes Isaj. “We are facing bureaucratic terrorism.”

*Not their real names because of fear of reprisals from Italian authorities and/or their employers.