Isaac Mutant, in and out of focus

The documentary Mutant presents a portrait of the rapper that, while unmuted, is strangely silent about many questions of coloured identity and his version of it.

Author:

16 December 2021

Many people who have heard of rapper Isaac Mutant, born Isaac Williams, would have done so in relation to Die Antwoord, a white South African rap-pop duo. Around 2008, Die Antwoord, comprising Ninja and Yolandi Visser, became viral for globally selling a version of “zef” that combined the culture of lower-class white people with elements of the working-class community classified as coloured under apartheid.

The urban legend among some coloured Cape Town rappers is that Ninja, real name Watkin Tudor Jones, took aspects of Isaac Mutant’s personality – including his punk-rock aesthetic and distinctive rap style in songs such as Kak Stirvy, Father’s Day, Wie Maak die Jol and Sorry Girl – and combined that with cultural symbols from coloured life as well as the “numbers” prison gangs. So he transformed himself from Max Normal (his stage name at the time) into a kind of “wigger” rapper – a pejorative term for a white person trying to emulate a Black person’s cultural behaviour – and packaged that into impoverished white noise for Euro-America.

Ninja and Yolandi then further parlayed this into recording sessions with Diplo and Marilyn Manson, music videos with hipster American filmmaker Harmony Korine and appearances at sold-out music festivals. As for Isaac Mutant, he did taste some of this fame, touring with Die Antwoord and featuring on some of their hits. But, so the detractors go, Die Antwoord left him behind. In this telling, Isaac Mutant became depressed, neurotic and ended up living rough, turning to Rastafarianism (not unusual on the Cape Flats), coloured identity politics (more on that later) and making little money from his music.

Related article:

Isaac Mutant eventually made a comeback with a new band, Dookoom. They made a song, “Larney, Jou Poes” (Your C***, Boss), which addressed the abuse by white farmers of their Black, especially coloured, workers on farms in the rural Western Cape. The song did not become a commercial success, but the video exercised a bunch of people in the media and white Afrikaans social movements because actors portraying coloured farm workers, led by Isaac Mutant on a tractor, burn down a farm.

The South African press, typically displaying enthusiasm for controversy rather than critical sense, decided there was a “debate” here. Much of it was about Isaac Mutant “abusing free speech” and that the song was confrontational to white South Africa. The press’ prevailing ethos is a version of an outdated rainbow politics, so they reflexively sided with white right-wing groups’ charge that it was hate speech against white farmers.

This, of course, is the classic response to anyone making any public comment about white privileges or the legacy of apartheid. Very few Black or coloured people cared. It was merely amplifying what they already know about life on the farms. Around the time the song came out, farm workers in the Boland (the fruit and wine production region of the Western Cape) had gone on an illegal strike to protest against working conditions, low wages, land hunger and racism by farmers. In fact, Isaac Mutant confirmed he was inspired by the revolt to make the song.

The film Mutant, directed by Lebogang Rasethaba and Nthato Mokgata, elides Isaac Mutant’s collaboration with and influence on Die Antwoord into one brief mention when he talks about some money he made recording with them that was stolen by people with whom he was living. As for Larney, Jou Poes, it is mostly included, one feels, to bolster Isaac Mutant’s credentials and notoriety: why the viewer should care about him.

The pain of Mitchell’s Plain

Isaac Mutant, 46, is from Vredendal, a rural town in the Western Cape situated about 160km from Cape Town on the way to Namibia. It was primarily attached to a larger military base under apartheid (South Africa occupied Namibia for much of the 20th century and the base was strategically close). As a young child, Isaac Mutant’s family, like many other rural coloured people, migrated to Cape Town for work and better opportunities. He grew up in Mitchell’s Plain, constructed in the late 1970s as a model township for coloured people as part of the state’s intensification of its “group areas” or racial segregation policies.

Mitchell’s Plain has the distinction of being South Africa’s largest coloured township. By Isaac Mutant’s teens, it suffered from all the pathologies of apartheid – joblessnes, overcrowding and gangsterism chief among them. He appeared to have a typical working-class childhood and, according to his only sister, he had a knack for staying in his room and writing rhymes.

Related podcast:

In his late teens, just as he was beginning to show an aptitude for rap, Isaac Mutant’s mother died and his father married a new wife a month later – “that chick chaila’d (left with) everything”. The new wife’s children moved in. It is unclear whether Isaac Mutant left or his father or new stepmother drove him out, but soon he was alternating between friends’ houses and sympathetic elders; the film continuously returns to a woman at whose house he stayed. During this time, he also became a young dad.

By the late 1990s, Isaac Mutant had developed a solid reputation as an MC, a battle rapper. He rapped in working-class Afrikaans about his prowess as a rapper, working-class life and relationships; he also, like many of his rap peers, became a spokesperson of all sorts for coloured working-class struggles.

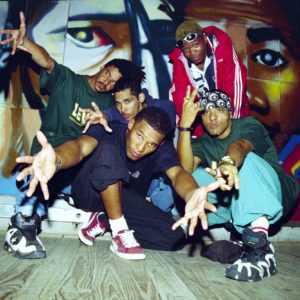

He ran with rap crews like Parliament, Koloured Ass Krooks and Plain Madnizz, the latter’s name a play on his home township. Isaac Mutant was also quite dismissive of MCs he didn’t judge to be his equal. In Mutant, Lee-Ursus Alexander, another MC who rhymes in Afrikaans, says of Isaac Mutant: “He hits the nail too hard.” He could afford to. As Die Antwoord was riding the wave of their United States breakthrough, he was opening for visiting rap luminaries like Public Enemy in 2009 and then joining them on stage.

An outsider figure

Over time, Isaac Mutant developed a sort of outsider persona as difficult to work with. It is a possibly unfair reputation, because what is difficult to some is having a particular artistic vision to others. As a rapper, he embodies a sort of South African combination of Joe Budden and the late XXXTentacion. (In Mutant, we learn that he had troubles with Dookoom’s record company.)

Isaac Mutant enjoys visibility and has been profiled in local media (one of the most outstanding pieces of journalism on him is by journalist and filmmaker Roger Young in the South African version of Rolling Stone magazine in 2013). But unlike his American counterparts, he hasn’t made a comfortable life from music. South African record companies, which Isaac Mutant detests, and DJs prefer bubblegum rappers. Isaac Mutant is also from Cape Town. To make money from rap, he’d have to move to Johannesburg.

Rasethaba and Mokgata’s film follows him around as he checks in on old haunts or close relatives with whom he seems to have mostly difficult relationships: his sister; her daughter; his own teenage daughter as she leaves school. The interaction with his daughter is brief but quite deep. Like any teenager (I have one, so I should know), she is dismissive when her dad and a camera crew arrive outside her school. Isaac Mutant tries to hug her, but she pulls away. She’s too old for this.

Related article:

But the interaction with her is also the one moment when he seems unsure of himself, at a loss for words. This is a moment when you see beyond Isaac Mutant’s bravado to his vulnerability. But the filmmakers are in a hurry as they want to make his life and the documentary about coloured identity politics in postapartheid South Africa.

This part of the film about coloured identity politics is less coherent and unfocused. Basically, it seems to suggest that coloured people are pissed at both white supremacy as a legacy of apartheid, and at perceived slights by a Black government and their fellow Black South Africans.

Isaac Mutant lives with his partner as a backyard squatter in the coloured part of Hout Bay, a picturesque but highly unequal tourist town on the Cape Town Atlantic coast. Any visitor to Hout Bay will be struck by its racial segregation: Imizamo Yethu on the Constantiaberg side is where the town’s Black population live. On the other side, on the slopes of the Sentinel, is Hangberg, a mix of squatters, formal row houses and maisonettes where coloureds live. This is where Isaac Mutant regroups. Down in the valley and further along the slopes of the mountain is white Hout Bay with its neatly laid-out ranch houses and mansions (and security), restaurants and malls.

Disjointed reductionism

In Hangberg, Isaac Mutant interacts and joins a group of Rastas. Their politics can best be described as a combination of nativism – a form of “first peoples” politics with lots of reference to them as “Khoisan” – and a Third Worldism borrowing heavily from reggae music and Caribbean millenarianism.

The tendency these days is to reduce all coloured politics to “Khoisan” homilies. This is presented as the only alternative for coloured political consciousness or political and economic advancement. No film or piece of journalism about Cape Town or the Western Cape is complete without it. Mutant is no different.

Hout Bay, like the farm workers’ revolt in the Boland, has been the scene of unrest among its coloured residents and the film wants to engage with that violence and protest, but it does so with little direction or focus. At most, it is a series of moving images, some taken from films like The Uprising of Hangberg, directed by Dylan Valley and Aryan Kaganoff, and with very little analysis about social and economic conditions or local politics, though Isaac Mutant tries to articulate residents’ anger.

Related article:

One thing clear from Mutant is that being coloured amounts to a form of Afro-pessimism. “We are doomed,” says someone at one point.

The film, oddly, also includes interviews with Ryland Fisher and Randall van den Heever. They act as talking heads. Both are older and important political and cultural figures in the region. In 1999, Fisher became the second Black (or coloured) editor of the Cape Times, established in 1876 and an important daily newspaper in the city. Fisher grew up on the Cape Flats and was involved in the mass movements of the 1980s and activist journalism under apartheid. As editor, Fisher launched “One City, Many Cultures”, a reporting project to bring coverage of the Flats into the mainstream of the paper’s very white suburban focus.

Van den Heever was a school teacher and unionist and, after apartheid, served as a member of Parliament for the ruling ANC. Both Fisher and Van den Heever make powerful comments about the political economy for coloureds after apartheid. At one point, Fisher makes an incisive point about the naked economic opportunism of many of the coloured elites driving “Khoisan” politics. But both their roles in the film are limited and miss a larger opportunity for comment. Which is a shame.

The politics of Afrikaans

Take Van den Heever, for example. In the 1980s, he was principal at Spes Bona, a prestigious boys’ high school in Athlone, one of Cape Town’s older coloured townships. He was also a leader of a progressive coloured teachers’ union allied to the internal resistance movement, the United Democratic Front. Near the end of apartheid, he also played a leading role in setting up the non-racial South African Democratic Teachers Union (an affiliate of Cosatu, the largest trade union federation in the country). It is how he became involved in the politics around “alternatiewe Afrikaans.”

Basically, in the mid to late 1980s, a group of Afrikaans teachers and writers promoted the creole origins of Afrikaans (the majority of its speakers are not white and the language originated in slavery). Crucially, they pointed out the language’s vibrancy among its mostly working-class coloured speakers and that this was not reflected in school syllabuses or pedagogy. I was in high school at the time, so I remember this well. Van den Heever and his colleagues proposed that coloured students should speak Afrikaans in class like they speak at home, that they not be penalised during, say, an oral presentation for not speaking “standard” (code: white) Afrikaans.

Related article:

During that time, another significant development happened in Afrikaans. While the white Afrikaans literature and publishing industry did include coloured Afrikaans writers in their anthologies or published a few of them – like PJ Philander, SV Petersen or, most significantly, Adam Small – Black Afrikaans writers felt marginalised. In response, a “swart Afrikaans” movement of poets (Patrick Petersen, André Boezak, Peter Snyders) emerged in the late 1980s. They soon published and amplified each other’s work.

To some extent, the swart Afrikaans poets created the environment for rappers like Prophets of da City, Brasse vannie Kaap and Isaac Mutant to rap in and make music in working-class coloured Afrikaans. These would be obvious things to speak to Van den Heever about, but the film is more superficially interested in identity – as symbol and cultural signifier – rather than the concrete conditions from which identities are continuously moulded and experienced.

By the end of the film Isaac Mutant says, “This documentary says everything I’ve been trying to say my whole life.” I am not entirely sure it does, but he is the subject, so I have to respect his opinion. In any case, Mutant contributes to the already growing legend of Isaac Mutant’s unruly genius and of the maddening politics of being a Black Afrikaans musician from South Africa.