Intifada 1987: The story of a rare Palestinian album

A rare recording featuring Palestinian artist Riad Awwad and poet Mahmoud Darwish has resurfaced, found amid a collection of 12 000 old cassette tapes in the West Bank.

Author:

12 April 2022

When Mo’min Swaitat stumbled upon thousands of cassettes in a dusty music shop in his home town of Jenin, he did not know that the treasure trove would lead him to uncover a significant moment in history. His journey across oceans led him to dig up a rare lost album, Riad Awwad’s Intifada 1987, found 34 years after it was originally recorded.

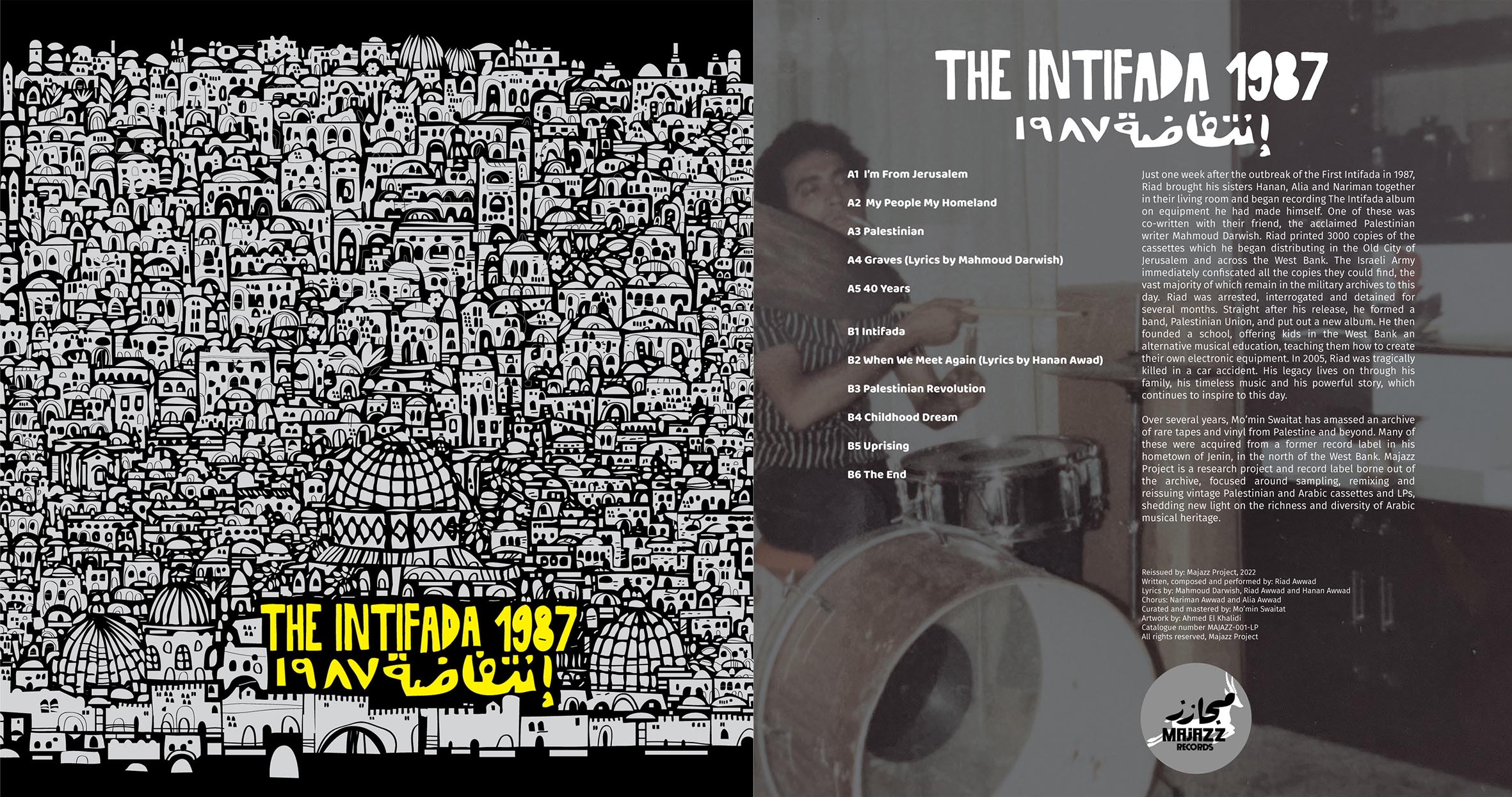

The album’s backstory unfolds in 1987 Palestine amid the First Intifada, mass uprisings by Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip aimed at ending Israeli occupation. A week into the Intifada, multi-instrumentalist Awwad gathered his three sisters, Hanan, Alia and Nariman, and their friend, famed poet Mahmoud Darwish, to record an album of 11 songs in their living room in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Awwad printed 3 000 tapes and circulated them to neighbouring cities. Upon release, the Israeli military seized the copies. But more than three decades later, Swaitat uncovered a mysterious unmarked tape containing the lost album.

An unlikely connection

An actor, playwright and director, Swaitat started his career in theatre at the Freedom Theatre in Jenin Refugee Camp in 2007. There, the theatre’s founder, activist and filmmaker Juliano Mer-Khamis, who was assassinated in 2011 for his powerful political work, mentored him. In 2012, Swaitat received a scholarship to study in London, where he now lives.

Swaitat went to Palestine with a German film crew in 2020, with the intention of staying for three weeks to film a documentary about Mer-Khamis. A week after he arrived, however, the world went into lockdown and he was unable to return. He stayed for a year at his parents’ home in Jenin.

Through the help of a family friend, he stumbled upon an old music shop, Taariq Cassettes, an oasis of thousands of Palestinian music cassettes. The shop had closed down years ago, but in its heyday had doubled up as a label that released tapes from the Palestinian archive, including revolutionary sounds, jazz, disco, funk, wedding and traditional music. The label had been defunct for the past 20 years and there were roughly 12 000 tapes in storage.

“It was completely abandoned. They allowed me to go inside the storage and look into what kind of music they had released as a label,” Swaitat says in an interview over Zoom.

An archive of history

For eight months, Swaitat went back and forth between the shop and his house, setting up his listening equipment in the space and searching for sounds of interest. He listened to as many tapes as possible.

Initially, Swaitat was looking for his own family archive, intending to make a music documentary. “I’m a Palestinian Bedouin and my family has a few bands who play at weddings,” he says. With some luck, he found most of his family sound archive in the store, amounting to nearly 400 cassettes, including recordings of his uncles’ and cousins’ weddings.

But that is not all he came across. “Then I found this massive Palestinian archive, with all of these different genres from the 1970s till the 1990s,” Swaitat says. The tapes included field recordings, interviews with Palestinian freedom fighters and leaders, and tapes recorded to pass on information during the First Intifada. He bought nearly 7 000 of them from the store.

When it was time to return to London, Swaitat managed to lug home five suitcases of roughly 2 000 tapes. Bound by London’s lockdown regulations, he spent months in his home studio listening repeatedly to the tapes.

Finding Intifada 1987

One particular cassette stood out. It was bright yellow with nothing on it save for a sticker with the words “Al Intifada”. He listened to it over and over again. “I really loved the sound of it. As a Palestinian, it gave me the feeling of amplifying my voice. It was poetic and the songwriting was very uplifting.”

Unable to identify the artist, Swaitat listened to the tape almost 10 times before he let it run all the way to the end, whereupon he heard a voice introducing himself as Riad Awwad and naming the other band members.

Were it not for this announcement, the tape would have remained in obscurity. Swaitat immediately started googling the names, eventually finding information on Hanan Awwad, a writer, poet and activist who worked with the Palestinian Liberation Organization. He reached out to her on social media, and Hanan welcomed a phone call.

“She was very happy that I reached out and said that she hadn’t heard the tape for the past 30 years,” he says. After sending her a digitised version, Hanan told him the tragic story behind the record.

One week after the Intifada broke out, her brother recorded the tape to capture his emotional state and contribute to the Intifada. Upon release and circulation of the album, the Israeli army confiscated most of the tapes over fears of their influence. Awwad was arrested, tortured and detained for months for creating the album.

Upon his release from prison, Awwad recorded another five-track album with a band called the Palestinian Union. He ran his own music shop in Jerusalem and studied sound engineering. He also founded a music school in the West Bank, teaching kids how to create their own electronic instruments.

“She told me he died in a car accident in 2004 and he never had managed to see this album released,” Swaitat says.

Intifada 1987 features Awwad as composer, singer and musician with contributions from his sisters as singers and songwriters. The album was made with homemade equipment, such as a “futuristic” customised keyboard, thus giving it a lo-fi, rough, textured sound. Darwish came on board after Hanan invited him to be part of the recording. His composition is a tune called The Graves.

Despite the violence and destruction unfolding around them during the Intifada, the album’s lyrical content is not focused on hate. Instead, it is a love letter to Palestine. The lyrics poetically describe the Palestinian landscape, the beauty of the mountains, sunrises and sunsets, nature, different animals and birds. But at the same time they tell a personal story of displacement of dreams since the Nakba and calls for liberation of freedom of movement, voice and existence.

Preserving memory

Palestinian cassettes used to be circulated to different cities through one tape that was copied. Mostly, this was to avoid Israeli checkpoints. “Many of these tapes came out with no artwork. Some came out with Hebrew writing, so the soldiers would leave them alone,” Swaitat says. This could be one possible way the tape survived. Swaitat consulted many Palestinian archivists. None had come across Awwad’s tape.

Swaitat initially approached a few labels about the archive, but soon realised this was not a good idea, given the music’s historical significance. “It’s not about the music only. It’s also about the story behind this. Who are those musicians? What happened to them and why were they involved in the first place?” he asks.

After giving it some thought, Swaitat established his own record label to deal with the tape archive. This is how the Majazz Project label was born, as a way to digitise and release the tapes. Swaitat works with a small team, including an archivist and artist, all dedicated to doing the work of research. For them, preserving the stories and uncovering these lost histories is important, to give a voice to and identity from a Palestinian perspective.

While continuing to work in theatre, Swaitat also hosts a monthly radio show called the Palestinian Sound Archive. He has some incredible releases planned with Majazz. One of its latest is a tribute to his teacher Mer-Khamis, which uses voice clips from the artist.

Palestine remains close to his heart, always. “All of my family is still there. I’m the only one who is not there. My family was forced to leave their original home town. My mom is from Keisarya and my dad is from Haifa. In 1948, the family was forced to leave their home during the Nakba, the catastrophe.”

Decades after Awwad recorded this album, its relevance is stronger now than ever, as occupation and displacement in Palestine and the struggle for land and identity continue. “I grew up into this [conflict] all my life. I was born in 1989, just two years after the First Intifada broke out. I had my first childhood memory during the First Intifada. And then I was a teenager during the Second Intifada from the age of 13.”

Intifada 1987 is due for its vinyl release in July, and will come complete with an Arabic/English translation of the lyrics. Because of its tragic history, Swaitat views the album as a release, not a reissue. The album would have been lost to history were it not for Awwad’s foresight to mention his name. This preservation allows for his story to be told and passed forward to inspire hope in a new generation.