Inquisitive show seeds its ideas in the viewer

An exhibition by Sisipho Ngodwana and Sinazo Chiya presents an expansive inquiry into being, engaging with questions rather than resolving them.

Author:

21 September 2021

It takes soil, sun, water, space and time to harvest corn grown from seed. This process is predictable. Heads of corn will be harvested between 60 and 100 days from planting. Visual artist Paulo Nazareth’s work Maze connects this reliable crop to the global masses of enslaved and exploited labour over centuries. His work presents a rectangle of yellow buckets, five wide and 10 deep, filled with soil and set on wooden pallets.

Maze was specifically created for the recent my whole body changed into something else group show, curated by Sisipho Ngodwana and Sinazo Chiya at the Stevenson galleries in Johannesburg and Cape Town. States of being and transformation form the soil that holds and feeds the system of related but separate concerns through which Ngodwana and Chiya toil.

“Initially, the exhibition started as an inquiry into trade systems, commerce,” says Ngodwana. “From realising CREAM, [that] cash rules everything around me, you can’t help but understand how many structures are influenced by [the] commercialisation of people and things. By extension, you have to realise that there’s so much that can’t … be commodified.

“I think it’s important that especially conversations like these happen in spaces of intense commerce or intense capital because we exist in these spaces. Our bodies are part of that commercialisation, because capital cannot exist outside of the body that it commodifies.

“It’s not an easy conversation to have and I think that’s the thing that we’re not shying away from. We’re not unaware of the privilege that only a commercial space will allow you to do something like this because it has the funds.”

Nazareth’s corn will not last longer than a year. Annual crops require seeding each planting season. This is, even in death, an interesting statement about commodities.

An expansive effort

The show is geographically, thematically and materially expansive, physically spread across two cities. It now also exists as an online viewing room. Existing works were selected and placed in visual conversation with commissioned works. The participating artists differed in eras, countries of origin and use of material. The ties that bind the artists to the other works in the show are delicately and densely woven, so the whole has its own particular logic.

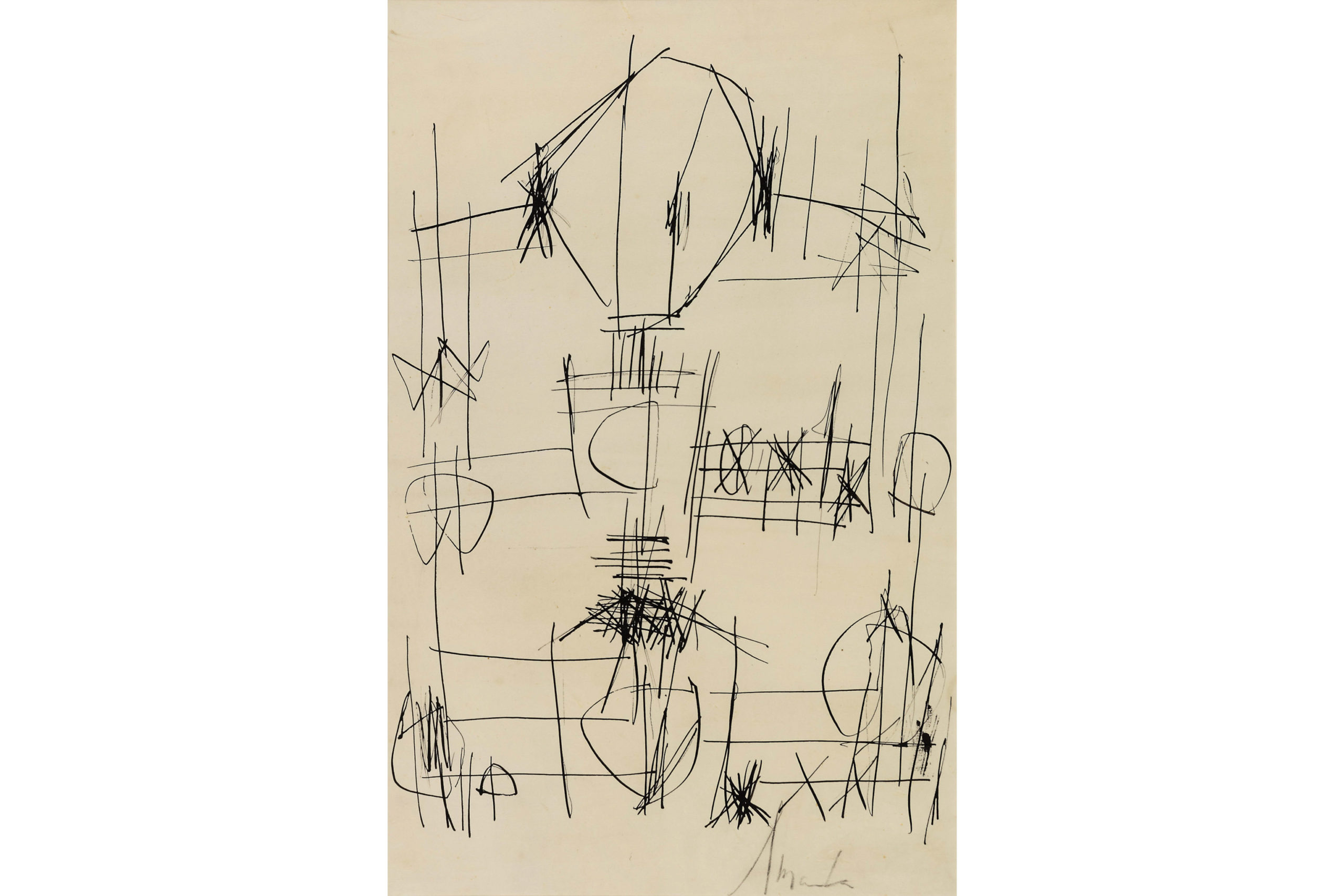

An untitled work by Ernest Mancoba, one of the earliest South African modernists who spent most of his life in western Europe, hangs in the centre of a white wall. A figure painted sparsely in the frame appears propped up by invisible forces on the canvas and the wall behind it.

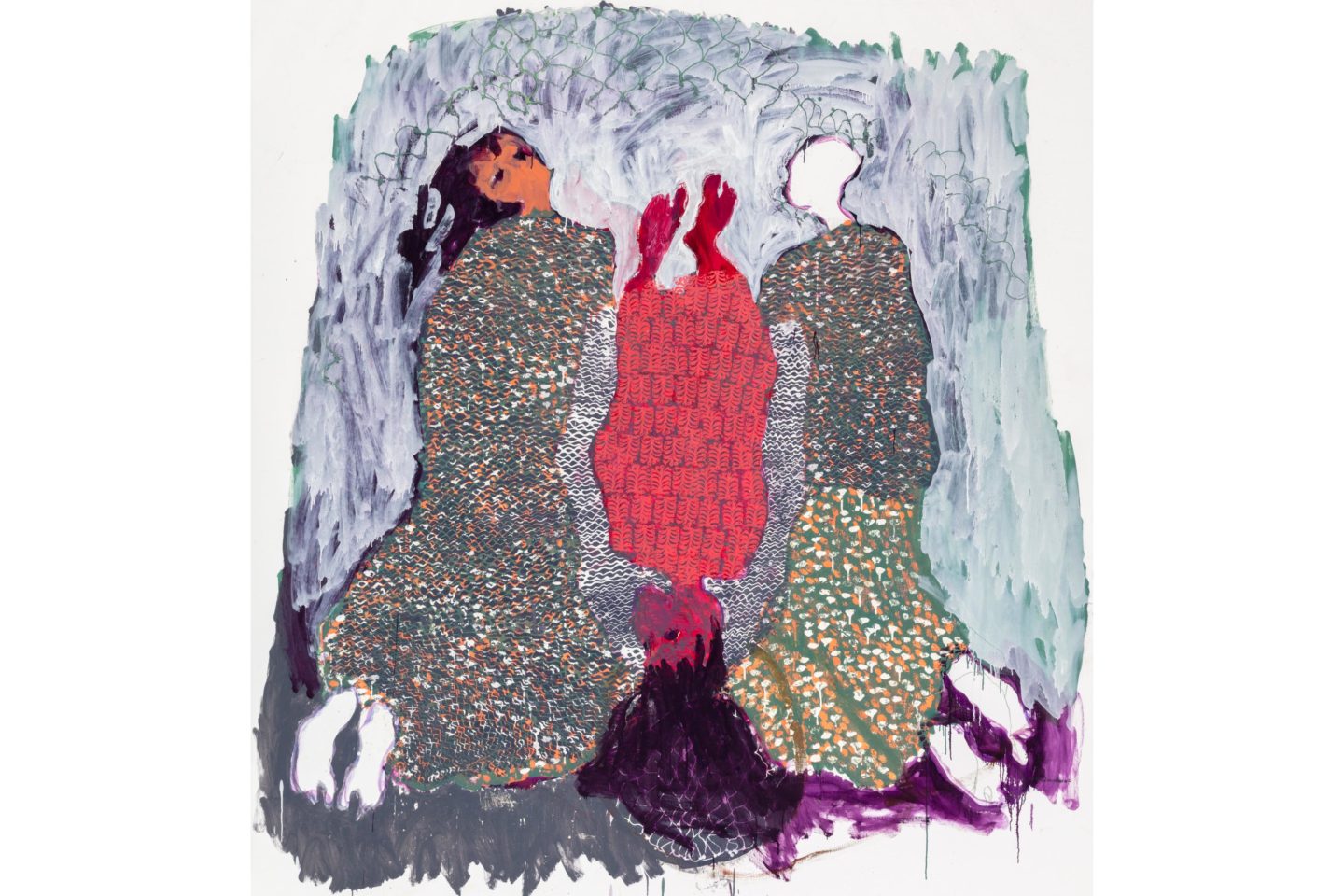

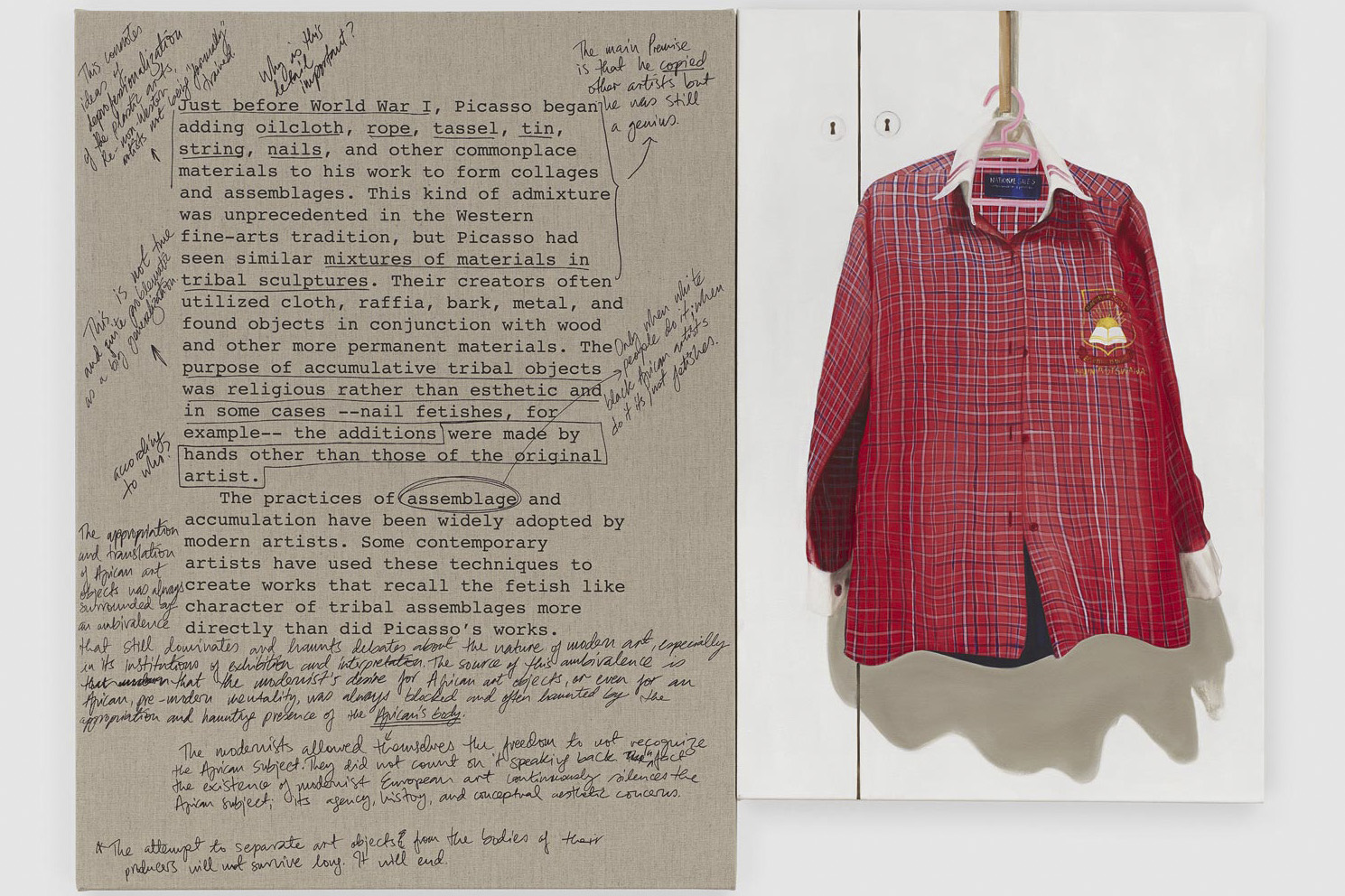

To the left of this is Objects of Desire, a photographic and textual work by Meleko Mokgosi, who was born in Botswana and exhibits and teaches primarily in the United States. To the right is Ndibuditsei Ipapo (Take Me Out of There), a painting by Portia Zvavahera, who lives and works in Zimbabwe.

my whole body changed into something else elicits transcendent moments. The art exudes an unignorable energy and meaning that adds to each other work in the show and to the exhibition as a whole. But this only goes so far. It is the individual artists who dig the troughs that plant seeds of meaning in the viewers’ minds.

“We started off with a list of artists that we wanted to work with because we understood their practice and what they were doing,” says Ngodwana, adding that they had a preference for artists on the move, who had been or were in some process of migration.

“It’s not necessarily about the object. I see the objects as totems of other things or other experiences. They are more signs. But at the same time, they are also their own realms. They are like bodies themselves … That was one of the defining things.”

Chiya says, “It was important to have modernists like Ben Enwonwu and Ernest Mancoba from that era, specifically Black modernists. It was also important to have ‘problematic’ white lens practitioners because that’s also part of the ecology of images and politics and embodiment that is necessary to speak about in this show as well.

“The temptation is to consider [the exhibition] esoteric but when you think of the very beauty of the technology of a seed, when you think of the soil, when you think of how the sky is so capable of renewal, there is so much that is transcendental in the everyday.”

Drawing from Sun Ra

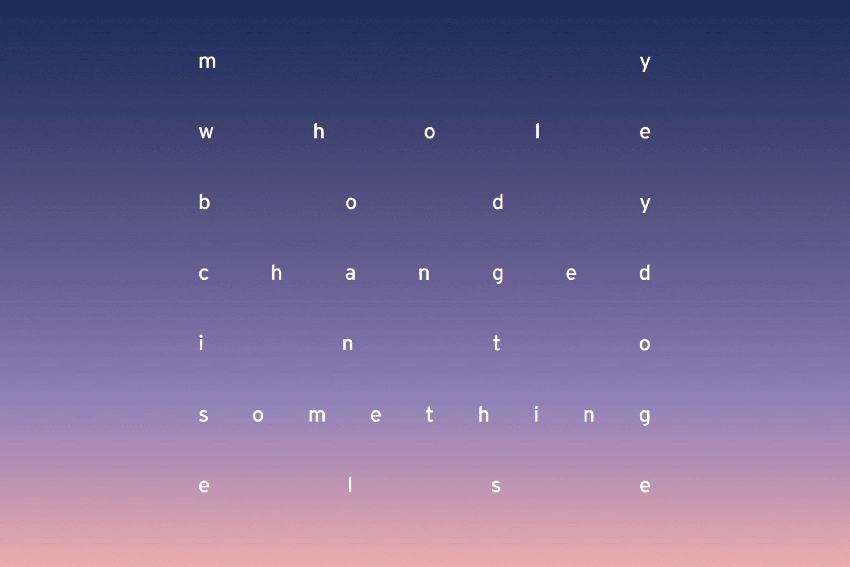

Ngodwana and Chiya took the show’s title from an incident US composer Sun Ra wrote about. Sun Ra has been called the instigator of the Afrofuturist movement. His music expressed a sense of transcendence he experienced and wanted to share with listeners.

Herman Poole Blount – which was his name before he became Sun Ra – was abducted by aliens in the late 1930s. Already a bandleader and on scholarship as music student at the Alabama State Agricultural and Mechanical Institute for Negroes, Blount said, “These space men contacted me. They wanted me to go to outer space with them … I’d have to go up with no part of my body touching outside of the beam … it looked like a giant spotlight shining down on me, and I call it transmolecularisation, my whole body changed into something else. I could see through myself. And I went up. Now, I call that an energy transformation because I wasn’t in human form. I thought I was there, but I could see through myself. Then I landed on a planet that I identified as Saturn.”

The curators of my whole body changed into something else consider the show to be an inquiry rather than an exhibition. It is about the transition between different dimensions and states of being. It considers ways of existing without necessarily holding fast to any one of the dimensions one occupies.

More art every day

In the broadest possible sense, more art is made each day than can ever possibly be hung in galleries. The show – or inquiry, as the curators have called it – benefits from financial and logistical support from some of the largest (read: monied) sentries of the global art market. It takes place in two of South Africa’s largest cities and has access to one of the largest catalogues of works in sub-Saharan Africa.

But it also suffers the ephemerality of a commodified and commodifying art trade. The primary imperative of commercial galleries is profit. This important work, however bold, will serve this imperative by giving new relevance and context to the works in the gallery’s catalogue.

In frayed and somewhat disjointed parts, speculative contemporary visual art in South Africa exists in different forms – adapting to constant change. These include provenance, online viewing rooms and artist and curator exhibition lists. For a new type of work to flourish in a sustained way, it will need constant tending, room for experimentation, accommodating spaces and a little luck.