In a US war on China, Australia would suffer

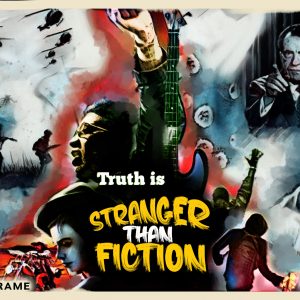

In Text Messages this week, fiction and reality blur as Aukus increases the possibility of a real-life confrontation as seen in the second film adaption of Nevil Shute’s On The Beach.

Author:

23 September 2021

New eras are always declared with aplomb but none has arrived with a bigger bang – and more disastrous consequences for the Earth and all things living on it – than the Atomic Age. Triumphally thrown around in the West while the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki smouldered in the deathly afterburn of radiation, the Atomic Age, the world was told, beckoned with all sorts of bright and shiny possibilities.

Not everyone was fooled. Writers began to grapple quite early on with the Armageddon potential of the A-bomb. English author Nevil Shute, having immigrated to Australia, published a hypothetical end-of-the-world novel, On the Beach, in 1957. World War III begins when Albania drops cobalt-enhanced atom bombs on Italy. Then the domino effect takes off: Egypt bombs the United States and the United Kingdom, Nato attacks the Soviet Union after mistakenly ascribing the Albanian and Egyptian attacks to the Soviets, who in turn send bombers to China.

For once, there is some small comfort to the divide between North and South for the latter. Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and the southern half of South America have not yet been affected by the fallout but will be in months to come. It is in this small window – the last days on Earth, as the title went of Shute’s earlier four-part version of this story – that On the Beach plays out. The story follows life in Melbourne and on the USS Scorpion, one of the last remaining American nuclear submarines.

Related article:

The film adaptation, released two years after the novel, remains a visual classic, its black-and-white images striking and austere and almost a modern equivalent of the doomsday scenes in Ingmar Bergman’s supreme evocation of death, The Seventh Seal. About 40 years later, the novel was turned into a Showtime mini-series and its plot updated. This version, released in 2000 and later as a feature film, set the story in the then-future of 2006, amid the nuclear devastation of a war between the US and China.

The cause of that war? China first blockaded Taiwan – the island state that until 1949 was a part of China – and then invaded it. Sticking to its agreement to defend Taiwan in case of attack by China, the US entered the conflict. Bombs away, a zero-zero sum game.

It’s a very plausible casus belli because the US does have such an arrangement with Taiwan, and China has long stated its intent to unify the “rebel island” or “breakaway province” with the mainland. Recently, Chinese diplomatic talk on Taiwan has been of the “two systems, one country” variety – the exact pact that China broke with Hong Kong.

Wrenching finale

This week the real world asserted itself even more over the fictional. The anglophone alliance Aukus (Australia-UK-US) – for which a more apt initialism would be Ausuk – increases the possibility of the kind of confrontation that the second On the Beach film posits. Aukus means military cooperation between its tripod of partners against China in the latter’s backyard, the South China Sea, and surrounds.

Hypothetically, it means that if China moved on Taiwan, Australia and Australians would find themselves on the front line of the US war on China. Australia would be a proxy for US naval and military presence in the region and it could well be Australians dying in an attempt to stop the occupation of Taiwan: in other words, Gallipoli II followed by a wider conflagration.

Related article:

Time, then, to revisit Shute’s classic and very humane book. Extremely unflinching also: as the fallout hits Australia and people become terminally ill, they queue for their government-issue suicide pills. Few contemporary novels are as wrenching as the final pages of On the Beach. From the heights of Barwon Heads, Moira watches the USS Scorpion sail out from Melbourne, bearing away her lover and its commander, Dwight Towers.

“She sat there dumbly watching as the low grey shape went forward to the mist on the horizon, holding the bottle on her knee. This was the end of it, the very, very end.”

Appropriately, Shute took the last four lines of TS Eliot’s poem The Hollow Men for his novel’s epigraph:

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.