Identity and indenture, in fact and fiction

The new novel, Children of Sugarcane, reckons with the “colonial fingerprints” on our contemporary society, while providing a nuanced view of indenture and its afterlives.

Author:

9 December 2021

Joanne Joseph isn’t as tall as she appears on television. This is the first, and most banal, impression of the former eNCA and SABC news presenter on our meeting at a Linden cafe on a mild Johannesburg spring morning.

The second follows quickly: Joseph is jolly good company. Like the easy ooze of egg yolk running into hollandaise sauce, our conversation shifts from identity politics to indenture, current affairs to literary criticism, the 19th-century cane fields of colonial Natal to this year’s fatal insurrection in post-apartheid KwaZulu-Natal.

There is a deep sense of mindfulness when she excavates family and community histories – and the colonial violence that runs through them. A lilt in her laugh when we move from the convivial to the conspiratorial in our conversation.

It is hard not to imagine that aspects of the protagonist Shanti in Joseph’s debut novel, Children of Sugarcane (Jonathan Ball Publishers), are based on the author herself, especially her independent mindedness and sense of injustice.

That suggestion receives an enigmatic response, but Joseph’s face lights up when I observe that her novel is a feminist text peopled by several strong female characters who aim to throw off the various yokes of their times.

Children of Sugarcane is – through its plot, characters and very creation – an extension of the “gynocritical approach” that academic Betty Govinden argues is required, to reinsert into South African stories and canons the literary endeavours, and lives, of women of South Asian descent.

Joseph is the latest in this approach’s lineage that, from memoir to academic writing to fiction, has produced writers like Phyllis Naidoo, Fatima Meer and Govinden herself.

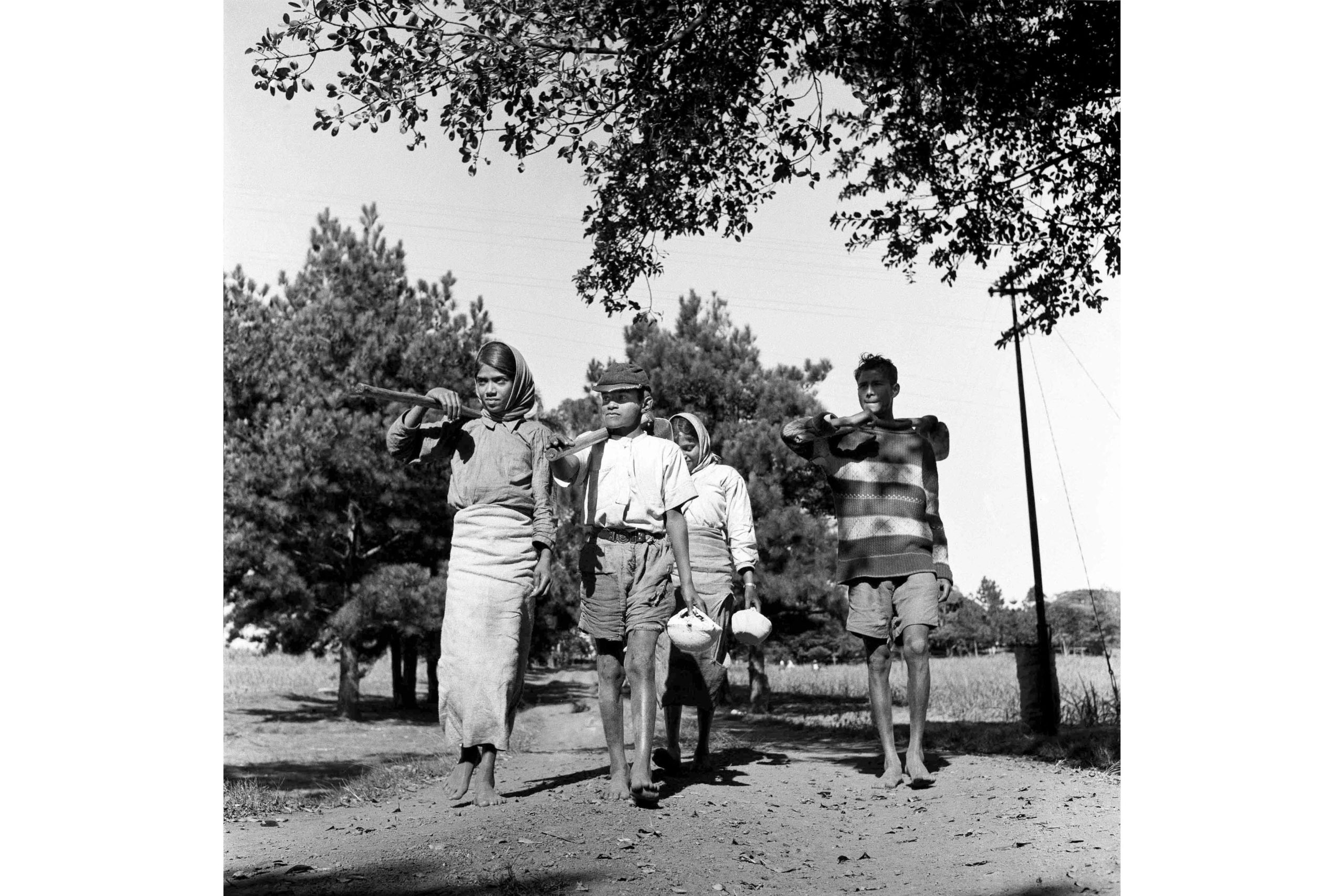

In Children of Sugarcane, Shanti, a young lower-caste girl from the Madras area of British-controlled South India in the late 1800s, clandestinely learns to read and write and has dreams beyond her station: to be a woman of letters rather than someone’s servant.

As a 14-year-old, she escapes her rural village and an arranged marriage to a cousin and begins a gruelling journey to a future in South Africa that initially promises liberation from the domination by men and the strictures of religion, caste and class. There is also the bait of undreamt-of financial reward that would transform the lives of herself and her elderly parents in India.

There are new freedoms for women in Natal, but also old violence, in the country that Shanti begins to consider making her own after falling in love outside her religion.

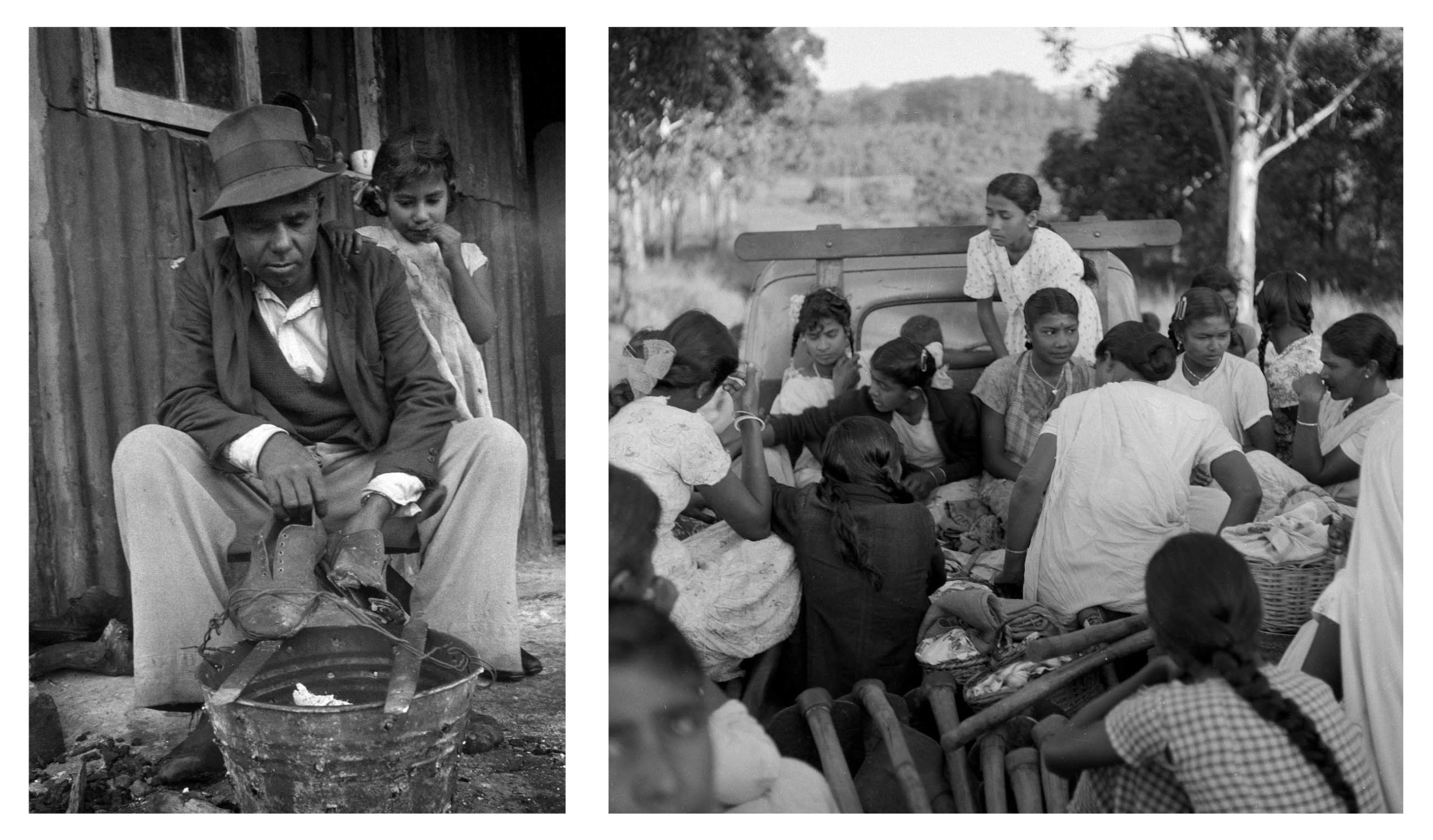

Shanti works as an indentured labourer on a sugarcane farm on the north coast of Natal. The system the British used to replace recently outlawed slavery remained brutally similar to its predecessor. Beatings and rape were rife, especially for women who had made the crossing over the kala pani (dark waters) of the Indian Ocean by themselves.

Rooted in research

Joseph’s fictional account of indenture is based on historical research towards a PhD and renders the novel chillingly evocative in its recreation of colonial abuse. She is a third of the way towards completing her doctoral project that examines narratives around female indenture and the shifting meanings of “Indianness” in South African literature.

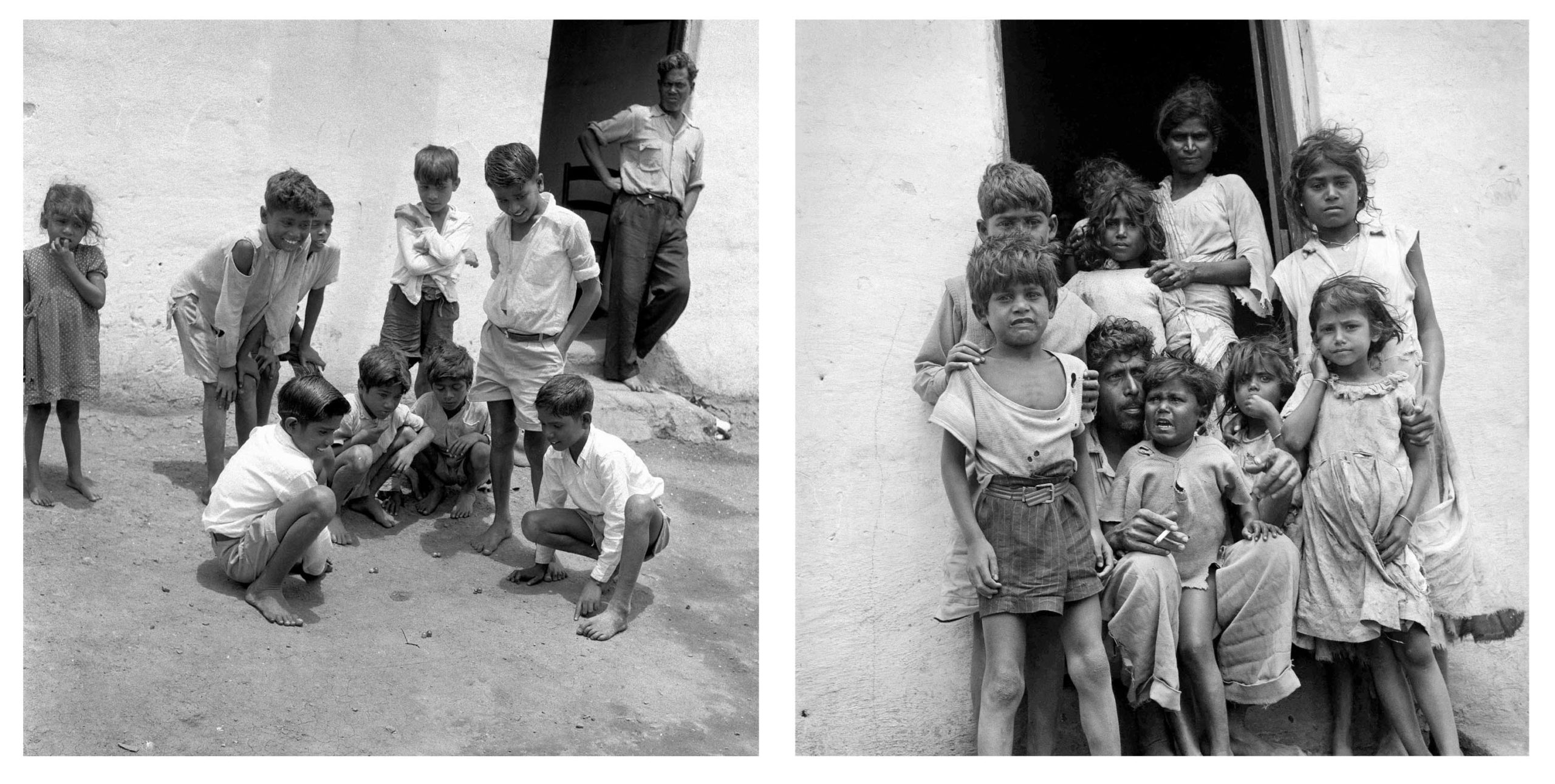

But, with a deft handling of the intimate stories of the characters populating the British Empire of the late 19th century – by delving into their dreams and nightmares, their participation in the small, everyday moments of rescued humanity and their ever-fluctuating notions of self that often transcends a mere response to colonialism – Joseph’s novel steers clear of casting its black characters as perpetual victims.

Instead, they live and breathe both within, and without, the colony, in a demonstration of agency that is restorative to a history often reduced to suffering. Some of her characters sing and dance in a determined celebration of who they are, others are mindful of their scars and how they are captive to them.

Joseph said she was intent on reflecting a more complex memory of indenture that was connected to slavery and “was premised on subjugation at one level, but, paradoxically, also presented people freedoms from caste and religion”.

She was intent on moving away from the “victimage” associated with indenture and wanted to reflect the nuances which informed people’s decisions to enter into the practice of bondage. These included the socio-economic reasons, like the wilful British destruction of Indian artisanship through taxation and legislation so as to create a market for the goods produced at its own rapidly industrialising “centre”, the droughts that wrecked places like the Madras Presidency, and the subterfuge and lies with which recruiters convinced people to head off to a land promising “milk and honey” and other abundant riches. And even the early birth pangs of a new nationalism springing from a country that had not previously considered itself a single entity before armed uprisings like the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857.

The character of Dilip, a sepoy on the run from the British in India who enters into the system of indenture as a consequence, is one such opportunity for this nuance according to Joseph: “It’s very easy to say that just the British perpetrated violence, but Dilip is experienced in it himself, both by his participation in the British army and, then, the uprising against them. He wants to put the violence behind him, but he knows his experiences of it makes him both a product and purveyor of that violence.”

Related article:

Dilip, as a result, appears as an avenger at moments in the novel, and also helps overturn another lazy stereotype that Joseph was keen to confront about indentured labourers: that they were “demure pacifists” drawing on passive resistance strategies and lacking a radical politics – which their descendants supposedly remain as until today.

Joseph cites the high incidence of suicides among the labourers, historical records of them setting fire to the crops on their masters’ farms and even the murder of their colonial overlords as an alternative to the inaccurate narrative of the quiet subservience of people of South Asian descent that still predominates in the South African mainstream.

“Suicide was a deeply political act,” Joseph says. “There was a sense among workers that they had been commodified within the capitalist system, that because the landowner had paid for their [oversea] passage and accommodation and so on, they had become a commodity, a piece of property. To punish the landowner for their abuses, some labourers paid the ultimate political act and removed themselves from the capitalist system – at their own hands.”

An urgent complexity

The reinsertion of a more complex historical identity for people of South Asian descent and their presence in, and relationship to, South Africa feels urgent at a time when racial tensions stoked by an ever-growing insidious fascism in the country and the populist demagoguery of mainstream political parties like the EFF and the DA appears to be gripping many South Africans.

A phenomenon made worse by untended racial fractures in communities in KwaZulu-Natal which reached an apogee of sorts during the July unrest and the killings of Africans in Phoenix, a community dominated by people of South Asian descent.

In recent times, there has also been a narrowing of the distance between whites and people of South Asian descent as citizens during apartheid – that in its socially engineered hierarchy, the latter benefited in material ways, and did not experience oppression, the pain of forced removals, the second-class citizenry of their existence, or the everyday violence and trauma at the hands of the regime. A revisionism that is ahistorical and premised on colonial divisiveness.

Joseph feels the anti-Indian language that is mainstreamed today is a demonstration of the lasting success of colonialism because South Africans still “experience each other through the mediated British gaze” which included a “careful and useful manipulation” of racist stereotypes, divide- and-rule tactics and “othering”.

Ever the journalist, Joseph identifies the EFF’s “conscious othering” of public enterprises minister Pravin Gordhan – who has taken on the alleged corrupt activities of the party’s leadership – in public, ad hominem attacks, as part of this regurgitation of reductive colonial codswallop. “Julius Malema and the rest of the EFF constantly refer to Gordhan by his middle name, Jamnadas, which is much less common and more difficult to pronounce. Why call him Jamnadas? The effect is to other him, to emphasise that he is a supposed alien to South African society. They are not criticising ‘PG’ on political grounds, but along racial lines,” she says.

Touched by history

“History is not a sectarian exercise, we are all touched by it,” says Joseph, as she observes that a people’s history of South Africa which is less stained by colonial fingerprints remains “elusive, inexplicable and inaccessible” to many South Africans – something which Children of Sugarcane seeks to address.

Joseph, who has previously published a work of non-fiction, Drug Muled: Sixteen Years in a Thai Prison: The Vanessa Goosen Story, has been working on the novel for more than eight years, with help and input from a range of people including editor Helen Moffett, Govinden, and her brother, Jeremy Joseph, who is a classical organist based in Vienna.

She concedes being “obsessed by fiction” and wanting to throw off the constraints of journalism and academic writing in pursuit of this insertion of new, more complex histories so as to address the failures of contemporary South Africans to understand each other.

“The conversation about decolonisation is incomplete if we do not revisit the colonised in all their forms and experiences,” she says.