‘I am Samuel’, an African love story against all odds

The makers of I Am Samuel about a daring relationship in a queerphobic society, went to extraordinary lengths to let their project see the light. Their government is not impressed.

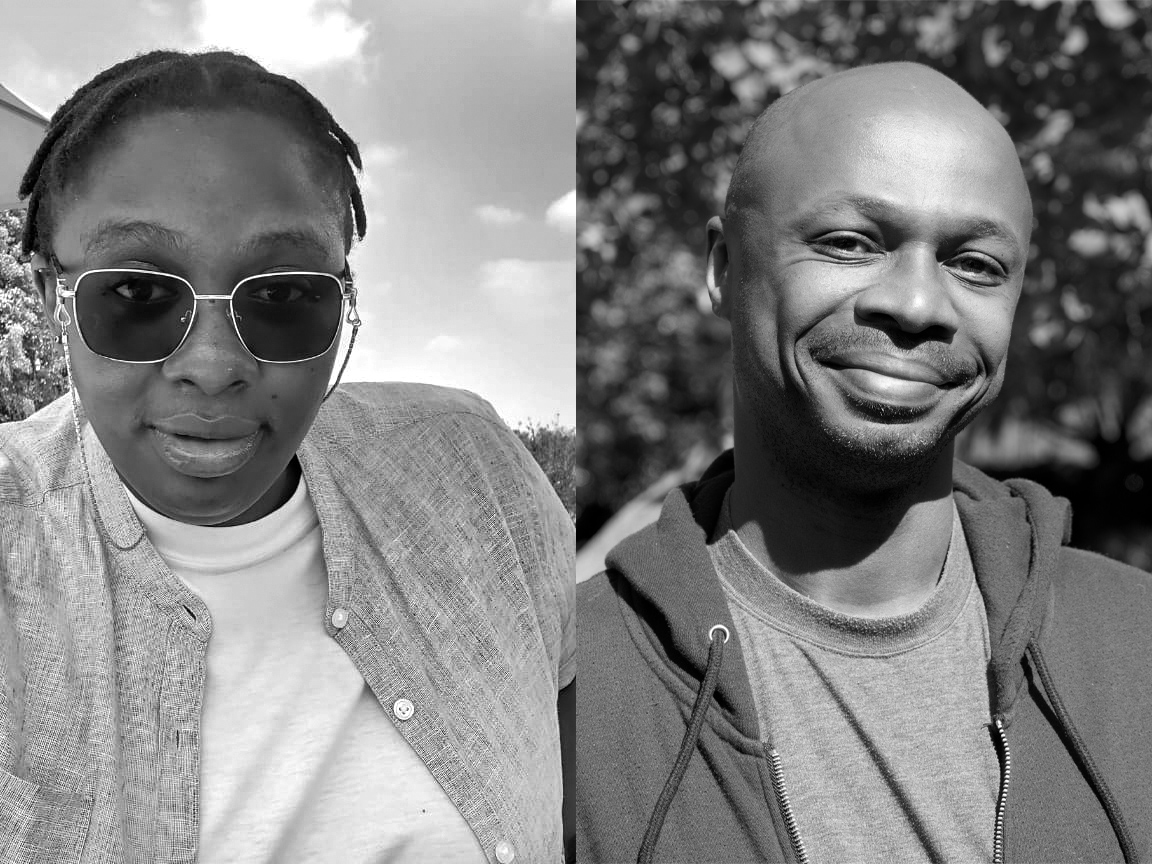

Author:

23 November 2021

The film I Am Samuel, hailed by some in the international media as a “meditative, optimistic documentary on queer love in Kenya” and “a work of true bravery”, was banned by the Kenya Film Classification Board shortly after its release. In a statement, the board labelled the film “an affront to our culture and identity” that violates “Article 45 of the Kenyan Constitution, which recognises the family as the basic unit of society and defines marriage as between two persons of the opposite gender”.

Directed by multi-award-winning documentary filmmaker Peter Murimi, the vérité-style documentary tenderly tells the story of Samuel, a soft-spoken, young gay Kenyan torn between his dreams of building a future with Alex, the man he loves, and the conservative views of his family and country.

In an edited interview, Murimi and the film’s impact producer, Annette Atieno, speak about putting together I Am Samuel in such a largely conservative environment, possible strategies to try to halt the Kenyan government’s continued banning of queer films, and why this queer love story is a quintessentially African story that took five years to film and another two to edit.

Carl Collison: Seven years? Was it difficult? Given the subject matter and where you were filming, it couldn’t have been easy?

Peter Murimi: In a sense, yes, it’s difficult… It was a very, very, very small team. Most of the time it was just me. And with a very small camera, so even in the communities where we were filming, I looked like just an amateur filmmaker. Because the profile – or rather the footprint – of the crew was really small, that really helped.

But the reason it took five years [of strictly filming] is because of how we were approaching the film. It was supposed to be, like, really intimate, and that requires building a lot of trust with the people that you’re filming. The only way to build trust is [to give it] time; there’s no shortcut to that. And especially because of the subject matter and the repercussions that could come with it, everyone is a bit sceptical. So it takes time for everyone to be on the same page and you have to go really slowly.

Collison: So, a lot of work creating trust, shooting, revisiting sites, interviewing, editing, and then the film gets banned in Kenya. How did that make you feel?

Murimi: It was disappointing, especially [because] I think this film… Kenyans would connect with it. Because it’s from Kenya and by Kenyans and it’s in Swahili [with English subtitles]. But putting that one side, this is also a film for Africa. And yes, I made it in Kenya, but the rest of Africa is enjoying it now and can watch it now. So we’ll take that. That’s a win.

Collison: What is the response to the film, especially across Africa?

Annette Atieno: We’re getting really positive responses, especially from the [queer] community. So people want to see the film. One of the comments that I remember and that I hold dear to my heart is “I’m glad to see a film about a Black, gay man shot through the lens of another Black man”. So there’s a strong identity to the movie, especially within the [queer] community, which I love.

Of course, Kenyans want to watch it. We’ve seen this a lot from the conversations they’re having on Twitter. Unfortunately, if you’re within the country, you can’t really watch it. But there has been really strong responses as well from the Kenyan [queer] community, because this is their story at the end of the day.

Collison: The film was not shown at the recent Out Film Festival in Nairobi. How do you feel, particularly as a queer person, that it is not available to Kenya’s queer communities?

Atieno: I love the Out Film Festival. I have attended every single year since I discovered it. It’s very unfortunate that, by and large, they’ve been unable to screen Kenyan films because of these bans. There [were two other queer films,] Stories of Our Lives and Rafiki and, now, I am Samuel [that have been banned]. And so it is sad that we cannot watch Kenyan films. But it is beautiful that we can still watch films from the African continent, because there are some intersectionalities. Though not many, there are some, and we are appreciative of that. It’s always good to see a queer story, no matter where it’s from. Because in my opinion, I feel like queerness is just this … family, right? So we reach across borders. It’s sad to not see Kenyan stories, but it’s great to see queer stories.

Collison: Were there times when people asked why you, a straight man, are doing a film on gay men in Kenya? Did you have to stand up for your project?

Murimi: Not directly. Nobody asked me, why this topic, why now? That never happened. But actually I was asking myself, am I the right person to tell the story? I had the commitment and I think my motivation was right, but I think sometimes, with each story, with each film, it’s as important who the person is telling it as the story itself. Because there’s that dynamic in the relationship that I think is really important. And during this process, there was a lot of self-examination, like, if I was the right person to tell this story. Eventually, my relationship with the family and with Samuel, I think, brought a lot into the narrative.

Collison: What was the impact of the film on Samuel and his family’s relationship? And Samuel and his community’s relations? Are their lives in danger?

Murimi: This was consistent throughout the making of this film: security. And especially in Kenya, because class buys you some protection. If you are queer and you [have] a little wealth, it’s a different story than Samuel [for whom] that safety net doesn’t really exist.

What I mean by that is if you live in a better place, which has better security, which is more private, it’s a safety net. It puts a distance between you and the people that could harm you. Samuel was living in Kariobangi [in Nairobi], and in these places [with] high-density populations everyone is very close to each other. So his security isn’t that guaranteed. If the film was released and he was still living exactly where he was, that could have been a big problem for his security and safety.

It became really clear that [for] Samuel it was not safe or practical to be in Kenya when the film was released. So that’s a sacrifice he had to make: being away from his family. His family has [also had] to make that sacrifice of their son being far away. It was a necessary sacrifice, but they were happy to do it. I think it was worth it and they think it was worth it. And I think it was the logical and most appropriate conclusion to how to safely handle the film while guaranteeing the safety of the main characters.

Collison: So they are not living in Kenya anymore? Where are they now?

Murimi: It’s top secret for now. They want to enjoy their time with some peace and quiet.

Collison: Are they planning on coming back to Kenya at any point?

Murimi: I don’t know. We don’t know. We’re taking it day by day. But they’re fine now, they’re doing really well.

Collison: Is there any way that you can negotiate with the government or the Film Classification Board, or to mobilise support for the screening of I Am Samuel there?

Murimi: There are two things. There’s a short-term view, but there is also the big game, the long-term game plan.

I don’t think it will change the circumstances, but we’re going to try to reason with the government, write a letter to the ministry and have a dialogue. But what is important is that this is the third queer film that is being restricted in Kenya and that Kenyans are being denied the chance to watch. So I think there has to be a bigger, long-term game [that will result in] hopefully this being the last film that has to go through this.

Part of releasing the film across Africa [is that] I think later down the line the government will see that there are so many other countries [with which] we share the same cultural values, [which] are very similar – Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, Ethiopia – and in all these countries you can watch I Am Samuel; it’s not banned. [We want to] go back to them a few months down the line and just say Africa has been watching this film. They’ve been debating. They’ve been talking about it. And look, the sky didn’t collapse. Nothing bad has happened. It’s just very healthy dialogue that has been going on.

And hopefully they will say, “Yes, maybe we are overreacting. If everyone can see it and so far it’s fine, maybe it’s us who are going a bit crazy.” So we’re going to have the dialogue. And hopefully in a constructive way.

This is our approach. There are other people who will go to court. And I think sometimes in a struggle you need every approach. Some people will go to battle and fight, some people will go to the negotiation table. And maybe combined, something will happen.

Collison: As a straight man, what is the one thing you hope the film will achieve?

Murimi: I don’t know whether I have only one hope. But I’d say that, at the beginning, my motivation for making this film was basically [to create] a film that will be very relevant to families that are similar to Samuel’s. Sometimes, when parents learn their child is queer, they think maybe their family is the only one on the planet going through the issue. I’m hoping this film tries to address that perspective, especially for parents, [that] they can see the world through their child’s perspective, which sometimes is missing. And also for children [to] see the world through their parents’ perspective.

In a sense, I’m hoping that it can bring families much closer, but also bring more understanding between each other. That was my motivation, actually: to [create] a film that can be very relevant to families that are dealing with issues that Samuel’s family is dealing with.

Collison: And for you, as a queer woman?

Atieno: I remember when I first watched the film, I hadn’t officially come out. And I told the film team this feels like my coming-out film. Because it’s such a… it’s a very raw story. And I love how it’s told.

It’s very touching. Samuel is a really good… I don’t want to say protagonist, but he carries the story well. It’s a beautiful story and I’ve enjoyed working on the project very much. I feel like it’s a film that families all over Africa can watch and can identify with. And there’s something in there for almost all queer folk, there’s something we can all identify with.

And that’s the beauty of the story. We can identify with being brought up in conservative families; we can identify with coming to the city to find work; we can identify with struggling to find work that is meaningful and that can sustain us. So it’s a beautiful story, and my hope is that as many families – families with queer children, with queer siblings, with queer parents – and as many people as possible can watch the film. Because it’s a very African story.

I Am Samuel is available on YouTube.